Outer space: The rule of two

Infinities are tricky things and have perplexed mathematicians and philosophers for thousands of years. Sometimes a never-ending list of numbers will become infinitely large; sometimes it will get closer and closer to a definite number; sometimes it will defy having any type of definite limit at all. A little while ago I was giving a talk about "Infinity" that included a look at the simple geometric series

$$ S = \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{4} + \frac{1}{8} + \frac{1}{16} + \frac{1}{32} + \frac{1}{64} +... $$and so on, forever. Every term in the sum exactly half the size of its predecessor. The sum of this series is actually equal to 1 but someone in the audience who wasn't a mathematician wanted to know if there was any way that he could see why that was true.

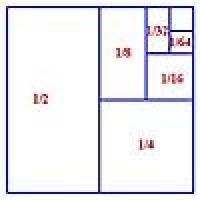

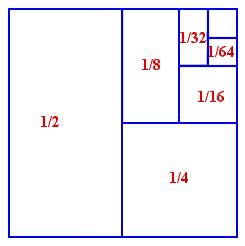

Fortunately, there is an impressive demonstration that just uses a picture. Draw a square of size $1 \times 1$, so its area is 1. Now divide the square in half, into two rectangles, by drawing a line from top to bottom. Each of them must have an area $\frac{1}{2}$. Now divide one of these rectangles in two to make two smaller rectangles, each with area equal to $\frac{1}{4}$. Now divide one of these smaller rectangles in half to make two more rectangles, each of area equal to $\frac{1}{8}$. Keep on going like this, making a rectangle of half the area of the previous one, and look at the picture. The original square has just had its whole area subdivided into a never-ending sequence of regions that fill it completely. The total area of the square is equal to the sum of the areas of the pieces that I have left intact at each stage of the cutting process and the areas of these pieces is just equal to our series $S$. So the sum of the series $S$ must be equal to 1, the total area of the square.

Usually when we encounter a series like $S$ for the first time we work out its sum in another way. We notice that each successive term is one half of the previous one and then multiply the whole series by $\frac{1}{2}$ so we have $$ \frac{1}{2} \times S = \frac{1}{4} + \frac{1}{8} + \frac{1}{16} + \frac{1}{32} + \frac{1}{64} +... $$ But we notice that the series on the right is just the original series, $S$, minus the first term, which is $\frac{1}{2}$ . So we have that $$ \frac{1}{2} \times S = S - \frac{1}{2}. $$ and $S$ = 1 again.

Here is a little problem involving this series. If you live in the United Kingdom you will know that the sales tax added on to many purchases is called "Value Added Tax", or VAT. It amounts to 17.5% of the price of the goods bought. If we suppose that the 17.5% rate of VAT was devised to allow it to be easily calculated by mental arithmetic, what do you expect the next increase in the rate of VAT to be ? And what will the VAT rate grow to be in the infinite future?!