Doing the twist

Perhaps the most sinister weather phenomenon in the world is the twister - that dark, dangerous funnel drooping from the clouds that weaves its way across the landscape, leaving a narrow trail of devastation in its wake.

One evening in early July, residents of the Selly Oak area of Birmingham got to witness this eerie event just a little too close for comfort - a twister formed which damaged 21 houses in its passage.

Mature tornado, Seymour, Texas, 10 April 1979.

D. Burgess, NOAA Photo Library

Probably as a result of their appearance in numerous Hollywood films, twisters are most commonly associated in the public mind with the United States. However, the American meteorologist Dr Ted Fujita discovered in 1973 that the UK actually has the highest frequency of reported tornadoes per unit area in the world.

The Met Office estimates that there are 30-50 tornados in the UK each year, but they are short-lived and often pass unnoticed across uninhabited countryside. 1982 was a particularly prolific year, with more than 150 tornados reported across the country.

Tornado in early stages of formation, Union City, Oklahoma, May 24, 1973.

c/o NOAA Photo Library

Tornados usually form during thunderstorms, but not always. If conditions are right - a combination of wind speed and direction changes - a horizontal spinning effect forms near the ground. As it is pushed upwards, it forms a vortex (becoming funnel-like), and if this funnel comes into contact with the ground the familiar tornado shape forms.

Some question whether global warming is responsible for events like the recent tornado in Selly Oak, but there is no evidence for this. Tornados are a normal part of the chaotic atmospheric events that make up the weather: difficult to predict, but likely to happen every now and then.

- Eyewitnesses

- A BBC Online story with eyewitness accounts of the Selly Oak tornado.

- Record breaker

- The record breaking Oklahoma City tornado.

Coda: Using mathematics to predict the weather

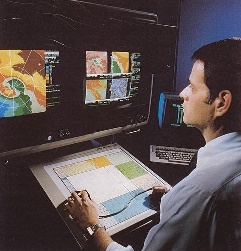

Modelling the weather.

c/o NOAA Photo Library

Weather forecasting is an extremely difficult mathematical problem. It is a branch of fluid dynamics: the term "fluid" refers to both liquids and gases, so the movement of air around the planet can be predicted by fluid dynamics. It's also important to take the effect of the oceans into account, as they have a major influence on air currents. In short, to predict the weather with any degree of accuracy requires a computer model of the surface of the entire Earth.

But it's possible for weather conditions to be completely different in two places just a short distance apart. For example, the Selly Oak tornado in July was only seen in a few streets. Trying to reconcile the computer model of the whole Earth, which is necessarily on a very large scale, with local weather patterns, which are on a much smaller scale of 1km or less, is one of the major difficulties involved in weather prediction. Mathematical and computational techniques are constantly being improved to try to deal with this.

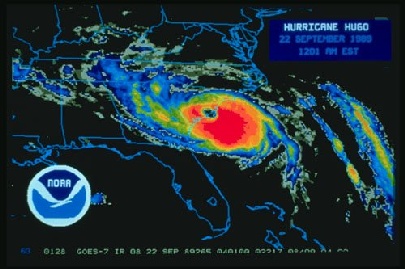

Satellite image of Hurricane Hugo, 22 September 1989.

c/o NOAA Photo Library

Another well-known difficulty is the so-called "butterfly effect" - a tiny movement somewhere in the world (such as, whimsically, a butterfly flapping its wings) can cause huge changes elsewhere several days later, because the chaotic nature of the weather magnifies any movements. So if any of the measurements taken by weather stations around the world are not 100% accurate - and they very rarely are! - then within a few days the forecast will be completely wrong. Weather forecasters have not yet started to blame their mistakes on rogue butterflies though!

Forecasting is likely to become more important, especially if global warming produces more violent weather in the UK, such as more frequent tornadoes. This is by no means certain, or even likely, but there's no doubt that we need to stay abreast of any new developments by continuing to improve our predictions.

PASS Maths interviewed Helen Hewson, who works at the Met Office, in Issue 3.