Advent calendar door #2: The double slit experiment

One of the most famous experiments in physics is the double slit experiment. It demonstrates, with unparalleled strangeness, that little particles of matter have something of a wave about them, and suggests that the very act of observing a particle has a dramatic effect on its behaviour.

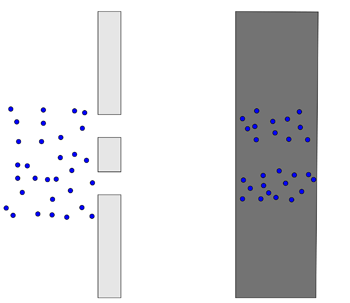

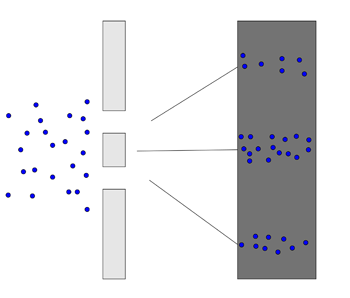

To start off, imagine a wall with two slits in it. Imagine throwing tennis balls at the wall. Some will bounce off the wall, but some will travel through the slits. If there's another wall behind the first, the tennis balls that have travelled through the slits will hit it. If you mark all the spots where a ball has hit the second wall, what do you expect to see? That's right. Two strips of marks roughly the same shape as the slits.

In the image below, the first wall is shown from the top, and the second wall is shown from the front.

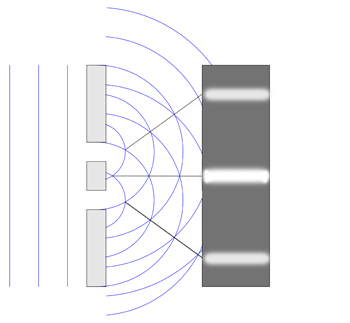

Now imagine shining a light (of a single colour, that is, of a single wavelength) at a wall with two slits (where the distance between the slits is roughly the same as the light's wavelength). In the image below, we show the light wave and the wall from the top. The blue lines represent the peaks of the wave. As the wave passes though both slits, it essentially splits into two new waves, each spreading out from one of the slits. These two waves then interfere with each other. At some points, where a peak meets a trough, they will cancel each other out. And at others, where peak meets peak (that's where the blue curves cross in the diagram), they will reinforce each other. Places where the waves reinforce each other give the brightest light. When the light meets a second wall placed behind the first, you will see a stripy pattern, called an interference pattern. The bright stripes come from the waves reinforcing each other.

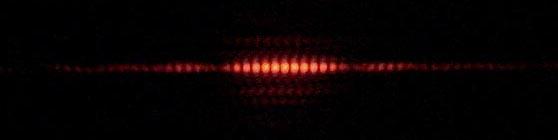

Here is a picture of a real interference pattern. There are more stripes because the picture captures more detail than our diagram. (For the sake of correctness, we should say that the image also shows a diffraction pattern, which you would get from a single slit, but we won't go into this here, and you don't need to think about it.)

Now let's go into the quantum realm. Imagine firing electrons at our wall with the two slits, but block one of those slits off for the moment. You'll find that some of the electrons will pass through the open slit and strike the second wall just as tennis balls would: the spots they arrive at form a strip roughly the same shape as the slit.

Now open the second slit. You'd expect two rectangular strips on the second wall, as with the tennis balls, but what you actually see is very different: the spots where electrons hit build up to replicate the interference pattern from a wave.

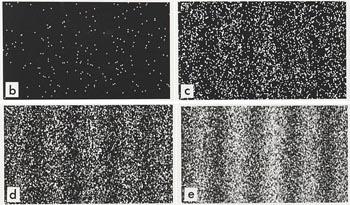

Here is an image of a real double slit experiment with electrons. The individual pictures show the pattern you get on the second wall as more and more electrons are fired. The result is a stripy interference pattern.

How can this be?

One possibility might be that the electrons somehow interfere with each other, so they don't arrive in the same places they would if they were alone. However, the interference pattern remains even when you fire the electrons one by one, so that they have no chance of interfering. Strangely, each individual electron contributes one dot to an overall pattern that looks like the interference pattern of a wave.

Could it be that each electrons somehow splits, passes through both slits at once, interferes with itself, and then recombines to meet the second screen as a single, localised particle?

To find out, you might place a detector by the slits, to see which slit an electron passes through. And that's the really weird bit. If you do that, then the pattern on the detector screen turns into the particle pattern of two strips, as seen in the first picture above! The interference pattern disappears. Somehow, the very act of looking makes sure that the electrons travel like well-behaved little tennis balls. It's as if they knew they were being spied on and decided not to be caught in the act of performing weird quantum shenanigans.

What does the experiment tell us? It suggests that what we call "particles", such as electrons, somehow combine characteristics of particles and characteristics of waves. That's the famous wave particle duality of quantum mechanics. It also suggests that the act of observing, of measuring, a quantum system has a profound effect on the system. The question of exactly how that happens constitutes the measurement problem of quantum mechanics.

Further reading

- For an extremely gentle introduction to some of the strange aspects of quantum mechanics, read Watch and learn.

- For a gentle introduction to quantum mechanics, read A ridiculously short introduction to some very basic quantum mechanics.

- For a more detailed, but still reasonably gentle, introduction to quantum mechanics, read Schrödinger's equation — what is it?

Back to the Plus advent calendar 2025

About this article

This article was originally published in 2017. Marianne Freiberger is Editor of Plus.