A brief history of mine

This is an excerpt from Stephen Hawking's address to his 70th birthday symposium which took place on 8th January 2012 in Cambridge. It is re-published here by permission. You can also listen to our podcast from the birthday symposium.

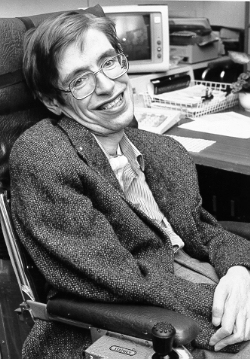

Stephen Hawking in the 1980s

Now that I reached three score years and ten, I hope you will forgive me for looking back over my life and how our understanding of the state of the Universe has changed. I will also try to look forward beyond the present horizon.

In 1950 my father's place of work moved to the northern edge of London, so my family moved nearby to the cathedral city of St. Albans. My parents bought a large Victorian house of some character but St Albans proved to be a somewhat stodgy and conservative place compared with Highgate. In Highgate our family had seemed fairly normal, but in St. Albans I think we were definitely regarded as eccentric. My father felt we couldn't afford a new car, so he bought a pre-war London taxi, and he and I built a Nissen hut as a garage. The neighbours were outraged, but they couldn't stop us. Like most boys I was embarrassed by my parents. But it never worried them. I think I learnt something from them because, later in life, I have often come up with ideas that have outraged my colleagues.

When we first moved to St. Albans, I was sent to the High School for Girls, which despite its name took boys up to the age of ten, but later I went to St. Albans School. I was never more than about halfway up the class. (It was a very bright class.) My classwork was very untidy, and my handwriting was the despair of my teachers. But my classmates gave me the nickname Einstein, so presumably they saw signs of something better. When I was twelve, one of my friends bet another friend a bag of sweets that I would never come to anything. I don't know if this bet was ever settled and, if so, which way it was decided.

I was twenty in October 1962 when I arrived in Cambridge at DAMTP, the Department of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics. I had applied to work with Fred Hoyle, the most famous British astronomer of the time. I say astronomer, because cosmology then was hardly recognised as a legitimate field. However, Hoyle had enough students already, so to my great disappointment, I was assigned to Dennis Sciama, of whom I had not heard. But it was just as well I hadn't been a student of Hoyle, because I would have been drawn into defending his steady state theory [which denies that there was a Big Bang], a task which would have been harder than saving the Euro.

You can read about Stephen Hawking's rise to scientific fame and the areas he worked on in the talk he gave at his 60th birthday. We pick up his 70th birthday speech at the point he turns his attention to the future of cosmology.

Stephen Hawking in 2006.

More recently, I wrote a new book, The Grand Design, with Leonard Mlodninov, to try to address a few issues left unresolved in [my book] A Brief History of Time. You see the laws of science describe how the Universe behaves, but to understand the Universe at the deepest level, we also need to understand why. Why is there something rather than nothing? Why do we exist? Why this particular set of laws and not some other?

I believe the answer to all these questions, is M-theory. M-theory is the only unified theory which has all the properties that we think the final theory ought to have. It is not a theory in the usual sense, but it is a whole family of different theories, each of which is a good description of observations only in some range of physical situations [find out more in the Plus articles Tying it all up and Stephen Hawking's 60 years in a nutshell]. M-theory predicts that a great many universes were created out of nothing. These multiple universes can arise naturally from physical law. Each universe has many possible histories and many possible states at later times, that is, at times like the present, long after their creation. Most of these states will be quite unlike the universe we observe and quite unsuitable for the existence of any form of life. Only a very few would allow creatures like us to exist. Thus our presence selects out from this vast array only those universes that are compatible with our existence. Although we are puny and insignificant on the scale of the Cosmos, this makes us in a sense lords of creation.

There is still hope that we see the first evidence for M-theory at the LHC particle accelerator in Geneva. From an M-theory perspective, it only probes low energies, but we might be lucky and see a weaker signal of fundamental theory, such as supersymmetry. I think the discovery of supersymmetric partners for the known particles would revolutionise our understanding of the Universe. I don't feel the same way about the Higgs boson [see Particle hunting at the LHC and Hooray for Higgs] which is why I bet one hundred dollars that it would not be found at the LHC. Physics would be far more interesting if it wasn't found, but it now looks like I might lose another bet.

Stephen Hawking experiencing zero gravity (Image: NASA)

Most recent advances in cosmology have been achieved from space where there are uninterrupted views of our vast and beautiful universe. But we must also continue to go into space for the future of humanity. I don't think we will survive another thousand years without escaping beyond our fragile planet. I therefore want to encourage public interest in space, and I've been getting my training in early.

So let me finish by reflecting on the state of the Universe. It has been a glorious time to be alive, and doing research in theoretical physics. Our picture of the Universe has changed a great deal in the last 40 years, and I'm happy if I have made a small contribution. The fact that we humans who are ourselves mere collections of fundamental particles of nature have been able to come this close to an understanding of the laws governing us and our universe is a great triumph. I want to share my excitement and enthusiasm about this quest. So remember to look up at the stars and not down at your feet. Try to make sense of what you see and wonder about what makes the Universe exist. Be curious. And however difficult life may seem, there is always something you can do, and succeed at. It matters that you don't just give up.