Win money with magic squares

Leonhard Euler, 1707-1783.

Magic squares have been known and studied for many centuries, but there are still surprisingly many unanswered questions about them. In an effort to make progress on these unsolved problems, twelve prizes totalling €8,000 and twelve bottles of champagne have now been offered for the solutions to twelve magic square enigmas.

A magic square consists of whole numbers arranged in a square, so that all rows, all columns and the two diagonals sum to the same number. An example is the following 4×4 magic square, consisting entirely of square numbers, which the mathematician Leonhard Euler sent to Joseph-Louis Lagrange in 1770:

| 682 | 292 | 412 | 372 |

| 172 | 312 | 792 | 322 |

| 592 | 282 | 232 | 612 |

| 112 | 772 | 82 | 492 |

It's still not known whether a 3×3 magic squares consisting entirely of squares is possible.

The prize money and champagne will be divided between the people who send in first solutions to one of the six main enigmas or the six smaller enigmas listed below. Solutions should be sent to Christian Boyer. His website gives more information about every enigma, and will contain regular updates regarding received progress and prizes won.

Note that the enigmas can be mathematically rewritten as sets of Diophantine equations: for example, a 3×3 magic square is a set of eight equations (corresponding to the three rows, three columns and two diagonals) in ten unknowns (the nine entries and the magic constant to which each line sums).

Here are the six main and six small enigmas:

How big are the smallest possible magic squares of squares: 3×3 or 4×4?

In 1770 Leonhard Euler was the first to construct 4×4 magic squares of squares, as mentioned above. But nobody has yet succeeded in building a 3×3 magic square of squares or proving that it is impossible. Edouard Lucas worked on the subject in 1876. Then, in 1996, Martin Gardner offered $100 to the first person who could build one. Since this problem — despite its very simple appearance — is incredibly difficult to solve with nine distinct squared integers, here is a question which should be easier:

- Main Enigma 1 (€1000 and 1 bottle): Construct a 3×3 magic square using seven (or eight, or nine) distinct squared integers different from the only known example and its rotations, symmetries and k2 multiples. Or prove that it is impossible.

| 3732 | 2892 | 5652 |

| 360721 | 4252 | 232 |

| 2052 | 5272 | 222121 |

How big are the smallest possible bimagic squares: 5×5 or 6×6?

A bimagic square is a magic square which stays magic after squaring its integers. The first known were constructed by the Frenchman G. Pfeffermann in 1890 (8×8) and 1891 (9×9). It has been proved that 3×3 and 4×4 bimagics are impossible. The smallest bimagics currently known are 6×6, the first one of which was built in 2006 by Jaroslaw Wroblewski, a mathematician at Wroclaw University, Poland.

| 17 | 36 | 55 | 124 | 62 | 114 |

| 58 | 40 | 129 | 50 | 111 | 20 |

| 108 | 135 | 34 | 44 | 38 | 49 |

| 87 | 98 | 92 | 102 | 1 | 28 |

| 116 | 25 | 86 | 7 | 96 | 78 |

| 22 | 74 | 12 | 81 | 100 | 119 |

- Main Enigma 2 (€1000 and 1 bottle): construct a 5×5 bimagic square using distinct positive integers, or prove that it is impossible.

How big are the smallest possible semi-magic squares of cubes: 3×3 or 4×4?

An n×n semi-magic square is a square whose n rows and n columns have the same sum, but whose diagonals can have any sum. The smallest semi-magic squares of cubes currently known are 4×4 constructed in 2006 by Lee Morgenstern, an American mathematician. We also know 5×5 and 6×6 squares, then 8×8 and 9×9, but not yet 7×7.

| 163 | 203 | 183 | 1923 |

| 1803 | 813 | 903 | 153 |

| 1083 | 1353 | 1503 | 93 |

| 23 | 1603 | 1443 | 243 |

- Main Enigma 3 (€1000 and 1 bottle): Construct a 3×3 semi-magic square using positive distinct cubed integers, or prove that it is impossible.

- Small Enigma 3a (€100 and 1 bottle): Construct a 7×7 semi-magic square using positive distinct cubed integers, or prove that it is impossible.

How big are the smallest possible magic squares of cubes: 4×4, 5×5, 6×6, 7×7 or 8×8?

The first known magic square of cubes was constructed by the Frenchman Gaston Tarry in 1905, thanks to a large 128×128 trimagic square (magic up to the third power). The smallest currently known magic squares of cubes are 8×8 squares constructed in 2008 by Walter Trump, a German teacher of mathematics. We do not know any 4×4, 5×5, 6×6 or 7×7 squares. It has been proved that 3×3 magic squares of cubes are impossible.

| 113 | 93 | 153 | 613 | 183 | 403 | 273 | 683 |

| 213 | 343 | 643 | 573 | 323 | 243 | 453 | 143 |

| 383 | 33 | 583 | 83 | 663 | 23 | 463 | 103 |

| 633 | 313 | 413 | 303 | 133 | 423 | 393 | 503 |

| 373 | 513 | 123 | 63 | 543 | 653 | 233 | 193 |

| 473 | 363 | 433 | 333 | 293 | 593 | 523 | 43 |

| 553 | 533 | 203 | 493 | 253 | 163 | 53 | 563 |

| 13 | 623 | 263 | 353 | 483 | 73 | 603 | 223 |

- Main Enigma 4 (€1000 and 1 bottle): Construct a 4×4 magic square using distinct positive cubed integers, or prove that it is impossible.

- Small Enigma 4a (€500 and 1 bottle): Construct a 5×5 magic square using distinct positive cubed integers, or prove that it is impossible.

- Small Enigma 4b (€500 and 1 bottle): Construct a 6×6 magic square using distinct positive cubed integers, or prove that it is impossible.

- Small Enigma 4c (€200 and 1 bottle): Construct a 7×7 magic square using distinct positive cubed integers, or prove that it is impossible. (When such a square is constructed, if small enigma 3a of the 7×7 semi-magic is not yet solved, then the person will win both prizes — that is to say a total of €300 and 2 bottles.)

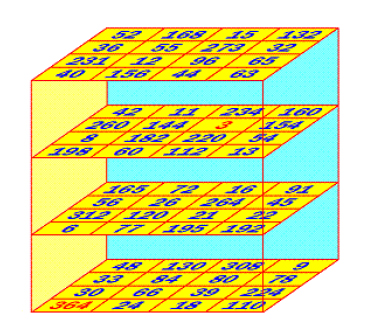

How big are the smallest integers allowing the construction of a multiplicative magic cube?

Contrary to all other enigmas which concern the magic squares, this one concerns magic cubes. An n×n×n multiplicative magic cube is a cube whose n2 rows, n2 columns, n2 pillars, and 4 main diagonals have the same product P. Today the best multiplicative magic cubes known are 4×4×4 cubes in which the largest used number among their 64 integers is equal to 364. We do not know if it is possible to construct a cube with smaller numbers.

A 4×4×4 multiplicative magic cube by Christian Boyer. Max number=364. P=17,297,280.

- Main Enigma 5 (€1000 and 1 bottle): Construct a multiplicative magic cube in which the distinct positive integers are all strictly lower than 364. The size is free: 3×3×3, 4×4×4, 5×5×5,... . Or prove that it is impossible.

How big are the smallest possible additive-multiplicative magic squares: 5×5, 6×6, 7×7 or 8×8?

An n×n additive-multiplicative magic square is a square in which the n rows, n columns and two diagonals have the same sum S, and also the same product P. The smallest known are 8×8 squares, the first one of which was constructed in 1955 by Walter Horner, an American teacher of mathematics. We do not know any 5×5, 6×6 or 7×7 squares. It has been proved that 3×3 and 4×4 additive-multiplicative magic squares are impossible.

| 162 | 207 | 51 | 26 | 133 | 120 | 116 | 25 |

| 105 | 152 | 100 | 29 | 138 | 243 | 39 | 34 |

| 92 | 27 | 91 | 136 | 45 | 38 | 150 | 261 |

| 57 | 30 | 174 | 225 | 108 | 23 | 119 | 104 |

| 58 | 75 | 171 | 90 | 17 | 52 | 216 | 161 |

| 13 | 68 | 184 | 189 | 50 | 87 | 135 | 114 |

| 200 | 203 | 15 | 76 | 117 | 102 | 46 | 81 |

| 153 | 78 | 54 | 69 | 232 | 175 | 19 | 60 |

- Main Enigma 6 (€1000 and 1 bottle): Construct a 5×5 additive-multiplicative magic square using distinct positive integers, or prove that it is impossible.

- Small Enigma 6a (€500 and 1 bottle): Construct a 6×6 additive-multiplicative magic square using distinct positive integers, or prove that it is impossible.

- Small enigma 6b (€200 and 1 bottle): Construct a 7×7 additive-multiplicative magic square using distinct positive integers, or prove that it is impossible.

Comments

Anonymous

Here is an "almost" magic square of squares, where all the rows and columns, and one of the diagonals sum to 21609. Sadly, the diagonal from top left to bottom right sums to 14358

94^2, 2^2 , 113^2

97^2, 74^2, 82^2

58^2, 127^2, 46^2

Arthur Vause

arthur dot vause at gmail.com

Anonymous

This is just the transformation of Lee Sallows's magic square (L. Sal lows, The lost theorem, Math. Intelligencer 19 (1997), no. 4, 51-54).

JohnG

is that a parker square?

spikyllama

this is a classic parker square

navin@371kumarshah

avause

Here is an "almost" magic square.

All rows and columns, and one diagonal sum to 21609. Sadly the diagonal from top left to bottom right sums to 14358

94^2, 2^2, 113^2

97^2, 74^2, 82^2

58^2, 127^2, 46^2

Kasper

I've pieced together a small script in Excel searching for a perfect 3x3 magic square of squares.

The first version was limited to search for integers between 1 and 1000. But I can't be the first one trying to brute force the main enigma 1 problem here. Not when there is a bottle at stake. But how far up in the integers have we searched for a solution?

Quinn

It has been mathematically proven that the smallest number in a complete 3x3 magic square of squares – if it even exists – would have to be larger than 10^14.

I would definitely recommend starting with the algebra before moving on to brute force. Personally, I've found a parametric formula which turns 4 variables of almost any arbitrary value into a 5/9 square of squares (the 4 corners and the center), and I've brute forced about 150 specific values which create 6/9 squares (the 4 corners, the middle, and one of the sides).

Out of all of the 6/9 squares that I have found myself, my favorite (per my love of horrifyingly large numbers) is the one with

17-digit square, 14-digit square, 18-digit square

18-digit non-square, 17-digit square, 15-digit non-square

14-digit square, 18-digit non-square, 17-digit square

However, I have not found a general parametric formula for generating 6/9 squares from any arbitrary value of variables, nor have I found any 7/9 squares by applying brute force to my 5/9 formula.

kevin oduor

well i reached 20 million on excel and gave up. good luck :)

Sav

I've find another magic square using 7 distinct squares. Is it worthy?

renes

Yes.

Because: Main Enigma 1 (€1000 and 1 bottle): Construct a 3×3 magic square using seven (or eight, or nine) distinct squared integers different from the only known example and its rotations, symmetries and k2 multiples. Or prove that it is impossible.

renes

I looked into that topic a bit and came to the conclusion that the smallest possible one with six squares is.

17^2; 35^2; 19^2

697 ; 25^2; 553

889 ; 5^2 ; 31^2

Maybe that is already known

Blue tit

Hi renes, I found an even smaller one, SUM: 435

5^2; 241; 13^2

17^2; 145; 1^2

11^2; 7^2; 265

Kevin

I checked all solutions up tot S=1,500,000. Did not find another 3 x 3 magic square of 7 or more distinct squared integers. I did however find many with 6. They seem to get more rare the higher you get. The last one I found was:

532^2/980^2/476^2

433552/700^2/546448

868^2/140^2/696976

S = 1,470,000

David Steadman

I'm interested as to how you check these. Could I possibly have some info on that?

rahuljha6204@gmail.com

Yeah that will be a great help if you tell how to check it using computer.. THANK YOU.

Because applying simple algebra, I have also found a magic square consisting of 6 out of 9 different square numbers which is already shown above in a message.The total sum is 1875.

35^2 (-311) 31^2

19^2 25^2 889

17^2 1561 5^2

Houston W.

I have the code that generates possible P values for it but I'm not sure how given the P value to check if there is a possible 4x4x4 multiplicative magic cube that works (and hopefully without having to try all 64! possibilities. Is there a pretty easy way to do this?

Blue tit

x and y are triangular numbers, and we know 8* any triangular number = an odd square.

1+8*(2*y); 1+8*(x+(2*y)); 1+8*(2*(x+y))

1+8*(y); 1+8*(x+y); 1+8*(y+(2*x))

1; 1+8*(x); 1+8*(2*x))

So if 2*x and 2*y are triangular numbers, then you automatically have 5 squared integers.

Then if two out of four possible options of: x+y or 2*(x+y) or x+2*y or y+2*x are triangular numbers. Then you have the 7!

Blue tit

X; 2*Y; Y+2*X

2*(X+Y); X+Y; 0

Y; 2*X; X+2*Y

SUM: 3*(X+Y)

If all entries are triangular numbers, then we know that 8 times any triangular number +1 equals an odd square. (0*8 + 1=1^2)

nikolih.

I think I may have solved this but I am afraid the solution I came up with is a few typed pages long. Is there an email or something I can send the proof to? Be warned its a little rough but all of the necessary ideas are there and if it isn't I'd gladly reply to questions.

Nikoli

This was the closest I could come but I’m unhappy with the answer. If you want to contact me- nikoliishot@aim.com

X being any positive integer. i being imaginary

(x sqrt(3))^2, ((x2)i)^2, (x)^2

((x sqrt(2))i)^2, 0, (x sqrt(2))^2

(xi)^2, (x2i)^2, ((x sqrt(3)i)^2

I’m formatting on a phone sorry

kevin oduor

has the impossibility of 3x3 magic square with 9 squared integers been prooven?

kevin oduor

if i prove that a 3x3 magic square of all 9 squared integers is impossible, do i win the prize?

JamesP

Nothing found under S = 1,200,000,000

JamesP

Searched until S=12,000,000,000,000 but could not find a solution for 9 distinct squares.

MKamenyuk

How is this even possible? Did you use Fugaku? =)

Nico Michaelides

3,46415849^2, 999,9694993^2, 7^2

999,9469986^2, 5^2, 9^2

9,695377457^2, 6^2, -999,9349979^2

Excel solver - if you need them in integers, just multiply out the decimals...

Quinn

You might want to double-check your math — none of the sums you provided line up with each other.

(We're also not supposed to use negative numbers)

Ayush Hansda

127² 46² 58²

2² √(12768)² √(8856)²

74² 82² √(9389)²

Ayush Hansda

Please 🙏 say if this format is correct

√(2)² √(7)² √(6)²

√(9)² √(5)² √(1)²

√(4)² √(3)² √(8)²

Rafael Pinero Gallardo

So my apophysis is that if I just put a lot of different versions of infinity some bigger than overs I know weird and put them in one square that would be allowed in the rules.

My 17x17 Square hope I win money

So basically my analysis is that there are many types of infinities bigger than others and I just if I just put them in one square I could win.

Michael T Chase

If x, y, z, s, t, r, o, p, and q are the spaces of the 3x3, then

x^2+y^2+z^2=

s^2+r^2+t^2=

o^2+p^2+q^2=

x^2+r^2+t^2=

x^2+s^2+o^2=

y^2+r^2+p^2=

z^2+t^2+q^2=

o^2+r^2+z^2.

If you then divide each equation by z, we get three parts of the equation that cancel z. Thus,

x^2+y^2=t^2+q^2=o^2+r^2. Therefore, if one can get six squares to equal each other, one will be closer the the answer of the 3x3. However, Wolfram Alpha posits the only real answer is zero.

Allison Felix

To demonstrate that it is not possible to construct a combination of 16 numbers that add up to exactly 256 in each row, column, and diagonal, we can use the parity method.

If we add up the numbers in a magic square of odd size (e.g. 3x3, 5x5, 7x7), the resulting sum is always an odd number. This is because each number on the main diagonal is counted twice, while each number on a secondary diagonal is counted only once. As there is an odd number of diagonals, the total sum will be odd.

On the other hand, if we add up the numbers in a magic square of even size (e.g. 4x4, 6x6, 8x8), the resulting sum is always an even number. This is because each number on a diagonal is counted only once, and there is an even number of diagonals. Therefore, the total sum will be even.

In the case of a 4x4 magic square, the sum of the numbers must be equal to 256. Since 256 is an even number, each row, column, and diagonal must add up to an even number. Therefore, if we add up the numbers on a main diagonal (which contains 4 numbers), we will get an even sum, as each number is counted twice. Similarly, if we add up the numbers on a secondary diagonal (which contains 4 numbers), we will get an even sum, as each number is counted only once. Therefore, the sum of the two diagonals will be even.

However, since the diagonals already add up to an even number, it is not possible for the rows and columns to also add up to an even number, unless some numbers are counted more than once. But since each number appears only once in a magic square, it is not possible to have an even sum in all the rows, columns, and diagonals. Therefore, it is not possible to construct a 4x4 magic square with a sum of 256 in each row, column, and diagonal.

To demonstrate this, we can use the following notation:

A1, A2, A3, A4 are the numbers in the first row;

B1, B2, B3, B4 are the numbers in the second row;

C1, C2, C3, C4 are the numbers in the third row;

D1, D2, D3, D4 are the numbers in the fourth row.

The sum of the numbers in each row, column, and diagonal can be represented as follows:

S1 = A1 + A2 + A3 + A4

S2 = B1 + B2 + B3 + B4

S3 = C1 + C2 + C3 + C4

S4 = D1 + D2 + D3 + D4

S5 = A1 + B1 + C1 + D1

S6 = A2 + B2 + C2 + D2

S7 = A3 + B3 + C3 + D3

S8 = A4 + B4 + C4 + D4

S9 = A1 + B2 + C3 + D4

S10 = A4 + B3 + C2 + D1

In order for it to be possible to construct a combination of 16 numbers that add up to exactly 256 in each row, column, and diagonal, all values of S1 to S10 must be equal to 256.

We can use the following equation to calculate the value of each sum:

Si = ai1 + ai2 + ai3 + ai4, where i is the number of the sum and ai1, ai2, ai3, ai4 are the four numbers that make up the sum.

We can rearrange the equation as follows:

ai1 = Si - ai2 - ai3 - ai4

We can use this equation to calculate the value of each number based on the values of the other three. For example, we can calculate the value of A1 as follows:

A1 = S1 - A2 - A3 - A4

We can use this same equation to calculate the value of all the other numbers.

However, if we try to apply this equation to all the sums, we will see that there is a conflict. For example, if we try to calculate the value of A1 using the sums S1, S5, and S9, we will get three different equations:

A1 = S1 - A2 - A3 - A4

A1 = S5 - B1 - C1 - D1

A1 = S9 - B2 - C3 - D4

These equations cannot all be true, because each number must appear only once in the combination of 16 numbers. Therefore, it is not possible to construct a combination of 16 numbers that add up to exactly 256 in each row, column, and diagonal.

Allison Felix

It is not possible to construct a magic square that is both additive and multiplicative, even if the sum and the product are different. To understand why this is true, we can use the distributive property of multiplication over addition.

Suppose we have a 5x5 magic square that is both additive and multiplicative, with a magic sum S and a magic product P. We can then write the following equations:

x₁ + x₂ + x₃ + x₄ + x₅ = S

x₆ + x₇ + x₈ + x₉ + x₁₀ = S

x₁₁ + x₁₂ + x₁₃ + x₁₄ + x₁₅ = S

x₁₆ + x₁₇ + x₁₈ + x₁₉ + x₂₀ = S

x₂₁ + x₂₂ + x₂₃ + x₂₄ + x₂₅ = S

x₁ * x₂ * x₃ * x₄ * x₅ = P

x₆ * x₇ * x₈ * x₉ * x₁₀ = P

x₁₁ * x₁₂ * x₁₃ * x₁₄ * x₁₅ = P

x₁₆ * x₁₇ * x₁₈ * x₁₉ * x₂₀ = P

x₂₁ * x₂₂ * x₂₃ * x₂₄ * x₂₅ = P

Now, if we multiply all the equations in the first list, we get:

(x₁ + x₂ + x₃ + x₄ + x₅) * (x₆ + x₇ + x₈ + x₉ + x₁₀) * (x₁₁ + x₁₂ + x₁₃ + x₁₄ + x₁₅) * (x₁₆ + x₁₇ + x₁₈ + x₁₉ + x₂₀) * (x₂₁ + x₂₂ + x₂₃ + x₂₄ + x₂₅) = S⁵

And if we multiply all the equations in the second list, we get:

(x₁ * x₂ * x₃ * x₄ * x₅) * (x₆ * x₇ * x₈ * x₉ * x₁₀) * (x₁₁ * x₁₂ * x₁₃ * x₁₄ * x₁₅) * (x₁₆ * x₁₇ * x₁₈ * x₁₉ * x₂₀) * (x₂₁ * x₂₂ * x₂₃ * x₂₄ * x₂₅) = P⁵

However, since the magic square is both additive and multiplicative, we can equate the two expressions above:

S⁵ = P⁵

But this contradicts Fermat's Last Theorem, which states that there are no integer solutions to the equation xⁿ + yⁿ = zⁿ when n is greater than 2. Therefore, it is not possible to construct a magic square that is both additive and multiplicative, even if the sum and the product are different.

Allison Felix

It is not possible to construct a magic square of cubes of order 6. Using modular arithmetic, we can show that it is impossible to obtain a sum of cubes that is a multiple of 6 or congruent to a multiple of 6 modulo 6.

If we cube both sides of the equation 6S ≡ 0 (mod 6), we get:

216S³ ≡ 0 (mod 6)

Simplifying, we get:

S³ ≡ 0 (mod 6)

Now, we can consider all possibilities for each value of the sum S:

• If S is a multiple of 6, then S³ is a multiple of 216, which means it is impossible to obtain a sum of cubes that is a multiple of 6.

• If S is a multiple of 3, but not of 6, then S³ is a multiple of 27, which means it is impossible to obtain a sum of cubes that is congruent to a multiple of 6 modulo 6.

• If S is not a multiple of 3, then S³ is congruent to 1 (mod 3) or -1 (mod 3). This means we cannot obtain a sum of cubes that is congruent to a multiple of 6 modulo 6.

Therefore, it is not possible to construct a magic square of cubes of order 6.

Allison Felix

Consider a 3x3 cube, where the numbers in each cell are represented as a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, and i.

The sum of all these numbers is 45 (a + b + c + d + e + f + g + h + i = 45), and the sum of each row, column, and diagonal must be equal to 15.

Let's assume that the sum of the numbers in each row is given by R, and the sum of the numbers in each column is given by C. We can then write the following equations:

a + b + c = R

d + e + f = R

g + h + i = R

a + d + g = C

b + e + h = C

c + f + i = C

a + e + i = C

c + e + g = C

We can then solve these equations to get:

a = (2C - R - e - i) / 2

b = (2C - R - d - f) / 2

c = (2C - R - e - g) / 2

h = (2C - R - b - e) / 2

g = (2C - R - h - i) / 2

f = (2C - R - d - b) / 2

Substituting these expressions into the equation for the sum of all the numbers in the cube, we get:

a + b + c + d + e + f + g + h + i = 45

Simplifying and rearranging terms, we get:

5C - 3R = 45

This equation implies that C and R must be odd and differ by a multiple of 3. However, this is not possible, since the sum of the numbers in each row, column, and diagonal of a 3x3 cube must be equal to 15, which is an odd number. Therefore, it is impossible to construct a semi-magic cube of order 3 using only cubes as the entries.

Navin Kumar shah

I got other magic square table which is similar to the Lee shallow magic square. Sadly, one of the diagonal sum is 465708.

218^2 , 313^2 , 314^2

103^2 , 394^2 , 302^2

446^2 , 62^2 , 233^2

Sum is 257049

navin@371kumarshah

Wellspring

I have a solution for a 4×4×4 magic cube.

I even disprove the Quist constraints

But Christian Boyer doesn't answer his email...

Navin451

I have three different magic square tables, each consisting of nine perfect square numbers. In each table, all rows, all columns, and one of the diagonals have equal sums, but unfortunately, the other diagonal does not have the same sum.

1418^2 , 6271^2 , 2162^2

6049^2 , 2458^2 , 1838^2

2722^2 , 802^2 , 6161^2

sum=46010409 and one diagonal's sum is 18125292

2458^2 , 6271^2 , 2729^2

6049^2 , 2969^2 , 2722^2

3191^2 , 2162^2 , 6161^2

Sum = 52814646 and one diagonal’s sum is 26444883

1418^2 , 6271^2 , 2729^2

6049^2 , 2969^2 , 1838^2

3191^2 , 802^2 , 6161^2

Sum = 48783606 and one diagonal’s sum is 26444883.