Curious dice

In this article we present a set of unusual dice and a two-player game in which you will always have the advantage. You can even teach your opponent how the game works, yet still win again! Finally, we will describe a new game for three players in which you can potentially beat both opponents — at the same time!

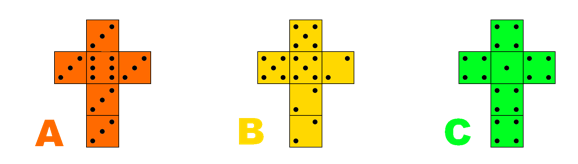

Our two-player game involves two dice, but they're not the ordinary dice we're used to. Instead of displaying the values 1 to 6, each die has only two values, distributed as follows:

| Die A: | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 6 | |

| Die B: | 2 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| Die C: | 1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

This is how the game works: each player picks a die and the two players then roll their respective dice at the same time. Whoever gets the highest value wins. Seems fair enough — but is it?

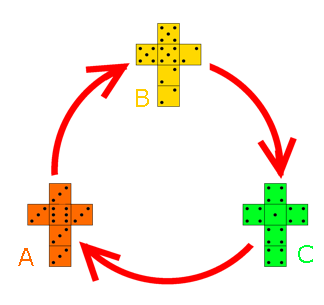

It can be shown (see below) that in the long run die A beats die B (it'll win against B more often than it'll lose against B), and that die B beats die C. So it appears A is the strong die and C is the weak die. So you might expect that, in the long run, die A beats die C:

If this were the case, then we'd call the dice transitive, as the winning property transfers via die B in the middle.

But it is not the case! In fact, the winning property goes round in a circle — like in a game of Rock, Paper, Scissors — with die A beating die B, die B beating die C, and die C beating die A (in the long run). There is no strong or weak die; the dice are what's called non-transitive. But how can this be?

Winning chances

Let's see why die A beats die B in the long run.

When you roll die A there are two possible outcomes; you either roll a 3 or a 6. The probability of rolling a 3 is 5/6, while the probability of rolling a 6 is 1/6. On the other hand, die B can either roll a 2 or a 5, each with a probability of 1/2. So in total, if we roll die A and die B together, we have four possible outcomes, as illustrated in the following tree diagram.

We find the probability of each possible outcome by multiplying the probabilities along the diagram. For example, the probability of rolling a 5 with die A and a 2 with die B is 5/6 x 1/2 = 5/12.

To find the probability that die A wins, add up the probabilities of all the outcomes where die A beats die B. So in this case, the probability die A beats die B (for which we write P(A>B)) is 5/12+1/12+1/12 = 7/12 — importantly, this is more than 1/2. So in a contest of several games die A is expected to win more often than die B.

In the same way it can be shown that in the long run die B beats die C, and then remarkably die C beats die A. (P(B>C)=7/12 and P(C>A)=25/36.) So, as long as your opponent picks first, you will always be able to pick a die with a better chance of winning. The average winning probability is (7/12 + 7/12 +25/36)/3 = 67/36, which is around 62%. It turns out that these three dice give a maximal set in the sense that they maximise the winning probabilities. But that's not the only surprising thing about them.

Double Whammy

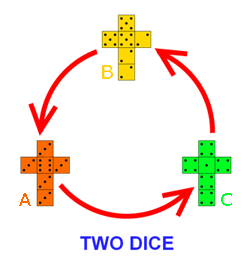

After a few defeats your opponent might become suspicious, so it's time to come clean and explain that you're dealing with non-transitive dice. You can give your opponent another chance, offering to pick your die first, so they should be able to pick a die with a better chance of winning. You can even offer a change in the game: each of you now rolls two of their chosen type of die. Surely, this means that your opponent has just doubled their chances of winning?

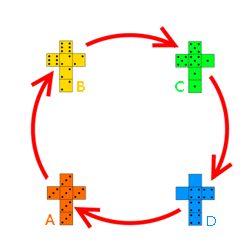

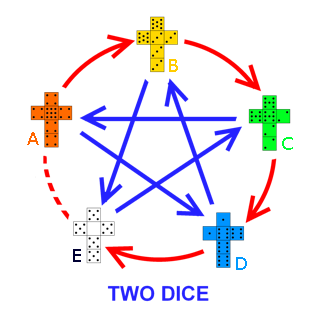

Not so! Amazingly, with two dice the order of the chain flips.

The chain reverses so the circle of victory now becomes a circle of defeat. Now, die A beats die C, die C beats die B, and die B beats die A, allowing you to win the game again!

The average winning probability with two dice is around 57%. The full probabilities are:

P(A > C) = 671/1296,

P(C > B) = 85/144,

P(B > A) = 85/144.

A word of warning though: although the probability that die A beats die C is greater than 1/2, it is a slim victory. In the short term, say less than 20 rolls, the effect is closer to 50-50, so you will still need some luck on your side.

Efron dice

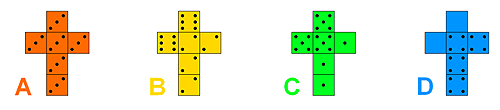

The idea of non-transitive dice has been around since the early 1970s. However, the remarkable reversing property is not true for all sets of non-transitive dice, for you do need to pick your values carefully. For example, here is another famous set of non-transitive dice, invented by the American statistician Brad Efron:

This time the dice use values 0 to 6. Each die has values:

| Die A: | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Die B: | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 6 |

| Die C: | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Die D: | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

As before, the dice form a circle with die A beating die B, die B beating die C, die C beating die D, and die D beating die A, and they each do so with a probability of 2/3.

We also have two pairs of dice opposing each other on the circle. In fact, die B beats die D, but die A and die C each have a 50-50 chance of winning, with neither die dominating.

Unfortunately, the player picking die A will not have a very exciting game, with all the values being the number 3. Also, this chain does not display the remarkable property of flipping when you double the number of dice. The probabilities for two sets of Efron dice are:

P(A > D) = 5/9,

P(B > A) = 5/9,

P(B > C) = 5/9,

P(C > D) = 5/9,

P(B > D) = 11/27,

P(D > B) = 0,

P(B = D) = 16/27 (a draw),

P(A > C) = 1/4,

P(C > A) = 1/4,

P(A = C) = 1/2.

The American investor Warren Buffett is reported to be a fan of non-transitive dice. When he challenged his friend Bill Gates to a game, with a set of Efron dice, Bill became suspicious and insisted Warren choose first. Maybe if Warren had chosen a set with a reversing property he could have beaten Gates — he would just need to announce if they were playing a one die or two dice version of the game after they had both chosen.

Three-player games

I wanted to know if there is a three player game, a set of dice where two of your friends may pick a die each, yet you can pick a die that has a better chance of beating either opponents — at the same time.

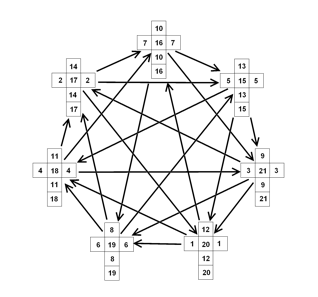

It turns out that there is. The Dutch puzzle inventor M. Oskar van Deventer came up with a set of seven non-transitive dice, with values from 1 to 21. Here two opponents may each choose a die from the set of seven, and there will be a third die with a better chance of winning than either of them. The probabilities are remarkably symmetric with each arrow on the diagram illustrating a probability of 5/9.

That's the probability of beating each individual opponent, but what about the chance of beating both at the same time? If the dice were regular fair dice, with two competing dice having a 50-50 chance of victory (ignoring draws), then the chance of beating two opponents at the same time would stand at just over 25%. It isn't exactly 25% because the event of beating one player isn't independent of the event of beating the other. This is because if you roll a high number, you're likely to beat both. In the case of van Deventer's dice, the chance of beating both opponents at the same time is around 39%. So even though you have the advantage against both opponents, beating both players is still a challenge.

Is it possible to construct a set of non-transitive dice with a higher chance of beating two players at the same time and possibly even involving less dice? Yes it is. I have devised such a set below.

Grime dice

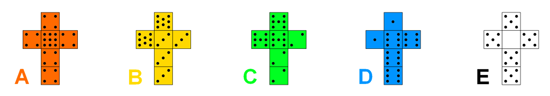

Here is a set of five non-transitive dice:

These dice use values from 0 to 9, as follows:

| Die A: | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 9 |

| Die B: | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 8 | 8 |

| Die C: | 2 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Die D: | 1 | 1 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Die E: | 0 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

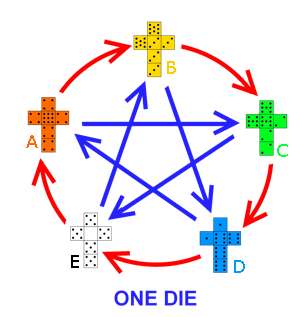

As with other sets of dice we have seen, we have a chain: A>B>C>D>E>A.

However, within that we also have a second chain: A>C>E>B>D>A.

The average winning probability for one die is 64.7%. The exact probabilities are

P(A > B) = 13/18,

P(B > C) = 2/3,

P(C > D) = 2/3,

P(D > E) = 13/18,

P(E > A) = 25/36,

P(A > C) = 7/12,

P(B > D) = 5/9,

P(C > E) = 7/12,

P(D > A) = 13/18,

P(E > B) = 5/9.

This means that given two dice, you cannot always find a third die that beats both. For example, this is the case when the two given dice are C and E.

If our original set of three non-transitive dice was like a game of Rock, Paper, Scissors, this diagram is closer to the related, but more extreme, non-transitive game Rock, Paper, Scissors, Lizard, Spock

With two dice the first chain stays the same. But the second chain now flips, so A>D>B>E>C>A.

The average winning probability for two dice is 59.2%. The exact probabilities are

P(A > B) = 7/12,

P(B > C) = 5/9,

P(C > D) = 5/9,

P(D > E) = 7/12,

P(E > A) = 625/1296 (a slim defeat, but in the short term the effect is 50-50),

P(A > D) = 56/81,

P(B > E) = 56/81,

P(C > A) = 85/144,

P(D > B) = 16/27,

P(E > C) = 85/144.

Overall, the average winning probability is 61.9%. This gives us a way of playing the game against two opponents: invite each player to pick one of the dice, but do not volunteer the rules of the game at this point. When the two other players have made their choice, you may now make your choice, including whether you and your opponents will be playing the one die or two dice version of the game. As before we play a game of say 10 rolls and, no matter which dice your opponents choose, there will always be a die with a better chance of beating each player.

For example, if one opponent chooses die B and the other opponent chooses die C, then you should pick die A and play the one die version of the game. Then, according to the first diagram above, you will have a better chance of winning than either individual opponent.

On the other hand, if one opponent chooses die C and the other opponent chooses die E, then you should pick die B and play the two dice version of the game. Then, according to the second diagram to the right, you can expect to beat each opponent again.

A gambling game

But, can we expect to beat the two other players at the same time? Well, we have certainly improved the odds, with the average probability of beating both opponents now standing at around 44%. That's a 5% improvement over van Deventer 's dice, and a 19% improvement over fair dice.

But if the odds of beating two players isn't over 50% how can we win? Consider the following gambling game:

Challenge two friends to a game in which you will play both of them at the same time. If you lose, you will give your opponent £1. If you win, your opponent gives you £1. So if you beat both players at the same time, you win £2; if you lose to both players, you lose £2; and if you beat one player but not the other then your net loss is zero. You and your friends decide to play a game of 100 rolls.

If the dice were fair, then each player would expect to win zero, since each player would be expected to win half the time and lose half the time.

With van Deventer 's dice, you should expect to beat both players 39% of the time, and lose to both players 28% of the time, which will give you a net profit of £22.

But with Grime dice, you should expect to beat both players 43.8% of the time, but only lose to both players 22.7% of the time, giving you an average net profit closer to £42! (And possibly the loss of two friends).

This set is the best set of five non-transitive dice with these properties that I have found.

I invite you to try out these games yourself. They are easy to make by either writing on blank dice, or modifying some old dice. Try them out on your friends and enjoy your successes and failures!

Here's a further challenge

For the very keen, here's a set to try that uses mathematical constants:

| Die A: | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | π |

| Die B: | Φ | Φ | Φ | e | e | e |

| Die C: | 0 | φ | φ | φ | φ | φ |

where e is Euler's number (2.718...), φ is the golden ratio (1.618...) and Φ is the conjugate of the golden ratio (0.618...). Do these dice form a non-transitive set? What about with two dice, does the order reverse as before?

Further reading

Find out more about non-transitive games in the Plus articles Winning odds and Let 'em roll.

About the author

James Grime is a lecturer and public speaker on mathematics, and can be mostly found touring the country on behalf of the Millennium Mathematics Project carting his trusty Enigma Machine. If you'd like James and the machine to visit your school, visit the Enigma website.

Comments

Anonymous

After making such a set of dice for fun, I noticed something I initially found surpising. After rolling all three dice, three consective values appeared e.g. 3, 4, 5. Nothing surprising in its own right but it happened immediately again, this time 4,5,6. In fact I struggled to throw any combintation that wasn't consecutive.

I found this very funny and strange, I think one's brain must be conditioned to not seeing a pattern and I think one also subcontiously fortget these are not normal dice. So when one sees

a sequence almost every time, you can't help but smile.

I did a few sums and I think the probability of this happening is about 83%. With a normal set of 3 dice you would expect this to happen 1.9% of the time. This I think expains why I am so amused by the effect.

This lead me to wonder if there is a similar set of dice that pushes the odds above 83%? I would like to know what set of 3 dice, covering all the usual numbers (1 to 6) yields the maximum probability of the 3 die values being consecutive?

Anonymous

Your calculation of (5/9)(5/9)=25/81 (31%) is incorrect, as it assumes that the probability of beating each opponent is independent. On the contrary, these two events are quite correlated. I've calculated the probabilities for several of the 35 triples, and the probability of winning for the "best" die has ranged from 1/3 (33%) to 13/27 (48%). I doubt that any of the 35 cases yields less than 1/3.

Best wishes,

Vadim Ponomarenko

Anonymous

You are quite right, sorry, blame calculation fatigue.

With Oskar dice, the probability of beating two opponents is 74/189 = 39.15%

With Grime dice, the probability of beating two opponents is 947/2160 = 43.84%

I'll ask for the changes to be made.

- James

Anonymous

Is there a set of 3 or 4 non-transitive dice with the same mean and variance?

Anonymous

Hi,

I'd really like to buy a set of Grime Dice,

but couldn't find it anywhere on the internet.

I am very interested in non transitive dice (Grime dice, Efron dice, Oskar dice,..), lots of good articles on the web, but nowhere to buy them !

please if you sell those dices or know a shop that sells them, let me know : Helvet5@hotmail.fr

++

Xavier.

Anonymous

I made my own by printing this net onto stiff card.

http://www.everydivot.com/dice

Anonymous

This may be a little late for you, but you can now buy Grime Dice at mathsgear.com

Anonymous

Hello, I'm interested in submitting for review a set of dice that satisfies a 4 player game.

Modeled after Oskar Van Deventer's 7-die set, this 19-die set uses 18 sides on each die, and each path on the digraph has an equal victory margin of 163/324. From what I've seen, the upper bound for the 19-die set is around 342 sides per die, so my set definitely brings it down. Coincidentally, 342 is the total number of sides throughout the whole set. The system is based on the 19-point digraph which can be seen here.

http://cp4space.wordpress.com/2013/02/15/tournament-dice/

Anyway, I'd love to have my work double checked if anyone cares to take a look. Each row lists the sides of a die.

A 5 21 39 76 94 111 128 142 160 184 200 218 236 254 271 288 321 339

B 4 36 53 70 87 102 117 145 162 183 196 213 230 266 281 296 305 341

C 3 32 48 64 80 112 125 148 164 182 192 227 243 259 272 304 308 324

D 2 28 43 58 92 103 133 151 166 181 207 222 237 252 282 293 311 326

E 1 24 57 71 85 113 122 135 168 180 203 217 231 264 273 301 314 328

F 19 20 52 65 78 104 130 138 170 179 199 212 244 257 283 290 317 330

G 18 35 47 59 90 114 119 141 153 178 195 226 238 250 274 298 320 332

H 17 31 42 72 83 105 127 144 155 177 191 221 232 262 284 287 323 334

I 16 27 56 66 95 96 116 147 157 176 206 216 245 255 275 295 307 336

J 15 23 51 60 88 106 124 150 159 175 202 211 239 248 285 303 310 338

K 14 38 46 73 81 97 132 134 161 174 198 225 233 260 276 292 313 340

L 13 34 41 67 93 107 121 137 163 173 194 220 246 253 267 300 316 342

M 12 30 55 61 86 98 129 140 165 172 209 215 240 265 277 289 319 325

N 11 26 50 74 79 108 118 143 167 190 205 210 234 258 268 297 322 327

O 10 22 45 68 91 99 126 146 169 189 201 224 247 251 278 286 306 329

P 9 37 40 62 84 109 115 149 171 188 197 219 241 263 269 294 309 331

Q 8 33 54 75 77 100 123 152 154 187 193 214 235 256 279 302 312 333

R 7 29 49 69 89 110 131 136 156 186 208 228 229 249 270 291 315 335

S 6 25 44 63 82 101 120 139 158 185 204 223 242 261 280 299 318 337

Anonymous

I'm sorry I'm 3 years late, but I have a set of three dice with slightly better overall probability than the ones you have. The dice (1,1,4,4,4,4), (3,3,3,3,3,3), (2,2,2,2,5,5) (I'll call them A, B, and C respectively) have an overall probability of 17/27=62.96%, slightly better than your 67/108 =62.04%. A beats B with probability 2/3, B beats C with probability 2/3, and C beats A with probability 5/9.