Happy birthday, London Underground!

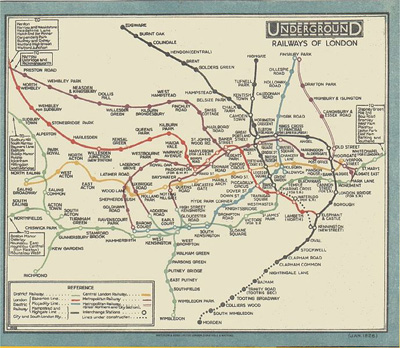

Part of the London Underground map. See the full map here.

The London Underground turns 150 today! It's probably the most famous rail network in the world and much of that fame is due to the iconic London Underground map. Millions of Londoners live with it imprinted on their brains while tourists carry it away with them on T-shirts, mugs, tea towels and even underwear.

But what makes this map so special? As far as geographical accuracy is concerned, you could hardly find anything worse. The distances between stations are distorted and so are the angles between the pretty colour-coded lines. "If you try to find your way around London on foot, the Underground map is about as useful as a Monopoly board," says John D. Barrow, a mathematician at the University of Cambridge. But it's exactly this inaccuracy that makes the map so easy to use. And it also makes it a work of design genius.

London Underground map from 1926. The outer reaches of the network are not part of the map.

The first maps of the London Underground were traditional kinds of maps, showing you where the lines ran under London in accurate geographical terms. "But this was horribly complicated," says Barrow. "Lots of stations [in the centre of London] were jam-packed close together, lines didn't go straight, and the outer reaches were far away. The map was hugely extended in order to get those far away places in and ridiculously crowded near the centre."

"By the 1920s the management of the London Underground were getting a little worried. People were not using the London Underground in the way they had expected. Revenue was falling and commercial disaster was a possibility. One of the reasons, it was suspected, was that people regarded a trip on the London Underground as very complicated. The map made the distances look enormous, changing lines looked complicated."

This is what a geographically accurate map of the modern Underground would look like. Click here to see a larger image.

A draftsman who worked for the London Underground, called Harry Beck, came up with an idea that saved the day. Beck ignored geography and instead focussed on the connections between stations. He magnified the central regions and brought in the far away ones. He laid the lines out to run either vertically, horizontally or at 45 degree angles. He stretched and squeezed London's geographical map to make the Underground network look good. And he also introduced the colour-coding and the little circles that mark intersections of lines.

The idea proved a huge success. "The sociology of London was influenced in many ways by that map," says Barrow. "People were prepared to live on the outer reaches of the Underground because the map made you feel close to the centre." The map has come to define the way many Londoners think about their home town. And many visitors never even notice that they are looking at a distorted London.

The seven bridges of Königsberg. Image: Bogdan Giuşcă.

Beck's background was in electronics and his idea inspired by the neat lay-outs of circuit diagrams. But it wasn't entirely new. In 1736 the mathematician Leonhard Euler solved a famous problem that had been making the rounds among intellectuals. The city of Königsberg (now Kaliningrad) was divided by a river with the various bits of land linked by seven bridges. The problem was to find a tour around the city crossing each bridge exactly once. Euler proved that this was in fact impossible, using an argument that had nothing to do with the actual geography of the city. It concentrated only on which land components were linked to which.

Euler's proof is often considered the starting point of an area of maths called topology. It ignores features such as distances and angles and considers only how things are connected. In topology any two shapes that can be deformed into each other by squeezing and stretching, but without tearing, are regarded as being the same. It's an idea whose uses go way beyond the world of maps. The shape of the Universe, the way DNA folds and the many networks that criss-cross our lives, from social networks to power grids, can all be understood using topological techniques.

Beck's map and its modern descendants are examples of topological maps. The next time you see one, whether it's on a rattling tube train or on a T-shirt, don't just think of London, think of maths.

Further information

- You can listen to John Barrow talking about the London Underground map in our podcast (starts after about 17 minutes).

- The Maths in the City website has great sections on the London Underground map and the Königsberg bridges problem.

- You can read more about topology on Plus.

Comments

Anonymous

For those who are interested to explore further, the Guardian did an article with 14 novel versions of the map:

http://m.guardian.co.uk/news/datablog/gallery/2013/jan/09/london-underg…