Outer space: Rowing has its moments

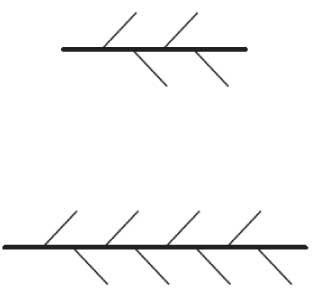

If you look at the pattern of rowers in a racing four or eight rowing boat then you expect to find them positioned in a symmetrical fashion, alternately right-left, right-left as you go from one end of the boat of the boat to the other. This pattern is called the rig of the boat and the conventional one we have just described is called the standard rig, shown here for a Four and an Eight.

The standard rig for a rowing Four and Eight.

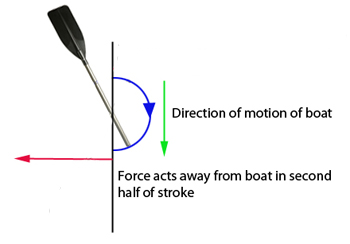

However, the regularity of the rower's positions hides a significant asymmetry that affects the way the boat will move through the water. Some time ago I looked at the rig of racing boats in a different way. Recall that in a rowing boat the rowers sit facing backward, so it is when they pull the oar towards them that the boat is propelled through the water. The pulling motion exerts a force on the boat in the direction of its forward motion. But since the end of the oar held by the rower describes a circular arc, there is also a second component to the total force acting on the boat at the rowlock. Its direction is at right angles to the boat's forward motion. During the first half of the stroke it is directed towards the boat but during the second recovery phase the force is in the opposite direction, at right angles to the boat but away from it. As a result the boat is subject to a sideways force that alternates, first towards the boat, then away from it.

On the first part of the stroke (top) the transverse force acts towards the boat and on the second part (bottom) it acts away from the boat.

The zero moment Four rig.

This seating plan is known as the Italian rig because it was discovered by the Moto Guzzi Club team on Lake Como in 1956. The crew of the Club's Four was being watched by Giulio Cesare Carcano, one of the company's leading motorcycle engineers from Milan, who suggested that the failure of the boat to run straight might be alleviated by putting the middle two oarsmen both on the starboard side with the stroke and the bow still on the port side. The result was rather successful and the Moto Guzzi crew went on to represent Italy and take the gold medal that year at the Melbourne Olympic Games.

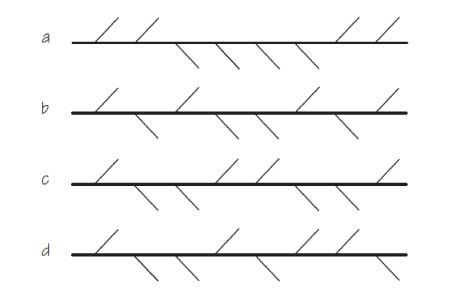

The situation for an Eight is more complicated. The standard rig produces a non-zero sideways moment that alternates between $-4Fr$ and $+4Fr$ during each stroke. The cox is going to have to work hard to counter that wiggle. But I found that there are only four possible ways that an Eight, crewed by identical rowers, can have a zero sideways moment. Here are the four no-wiggle rigs:

The four possible rigs for Eights which have zero transverse moment. (a) The new rig 1: uudddduu; (b) The German rig: ududdudu; (c) The Italian rig: udduuddu; and (d) The new rig 2: udduduud.

Finding no-wiggle rigs for the Eight

Notice that in the formula for the sum of the moments of the transverse force s is cancelled (because there are an equal number of rowers on each side of the boat) and r always ends up multiplying F. Because of this the problem of finding a no-wiggle Eight is solved by finding all the ways to combine the numbers from 1 to 8 with four plus signs and four minus signs (corresponding to four rowers on each side of the boat) so that the result is 0. The four solutions I found correspond to the four ways to do this, which are 1+2-3-4-5-6+7+8 for (a), 1-2+3-4-5+6-7+8 for (b), 1-2-3+4+5-6-7+8 for (c), and 1-2-3+4-5+6+7-8 for (d). It can be shown that zero-wiggle rigs are only possible if the number of rowers is exactly divisible by 4.

Rig (c) is just two of the Italian rigs for a Four set one behind the other. Rig (b) is the so called German, bucket, or Ratzeburg rig, first used by crews training at the famous German Ratzeburg rowing club in the late 1950s under Karl Adam, who was motivated by Carcano's configuration for the Four. The other two rigs are new.

When I published these results they attracted a lot of attention around the world and there were articles about them in World Rowing Magazine. The results were then confirmed in greater detail in an article in the Rowing Biomechanics Newsletter. New Scientist magazine then prepared a long article about them and commissioned some trials on the River Thames with the Imperial College Eight (see the picture below) to see how they liked the new rig (a) compared to the standard one. Then I discovered that the winning Canadian Men's Eight used the German rig (b) in their gold medal race at the Beijing Olympics and Oxford did the same to win the 2011 University Boat Race on the Thames – the first time a non-standard rig had been used in the race for 40 years. However, the reason was one of convenience in fitting in some outsized oarsmen rather than the desire to be wiggle-free. Perhaps someone will try my (a) or (d) in London 2012.

A trial of one of the new rigs on the Thames, organised by New Scientist. Image copyright Mark Chilvers.

Comments

Anonymous

Actually Cambridge tried it in the boat race!!

Not sure if they won for that, to be fair...

Anonymous

Cambridge did use it this year 2012, but Oxford alone did it in the boat race in 2011.

Anonymous

Bit hard to tell on the TV coverage here, but looked very much as though the gold medal-winning German Men's Eight used rig B above in the final of the London 2012 Olympics yesterday.

Video of the race on the BBC at http://www.bbc.co.uk/sport/0/olympics/18905503

Anonymous

> The standard rig produces a non-zero sideways moment that alternates between $-4Fr$ and $+4Fr$ during each stroke. The cox is going to have to work hard to counter that wiggle

I don't think so. Because the net force over a stroke is zero, the cox can just ignore it, and it will even out.

The other problem here is that your analysis is non-quantitative: to know whether this is worth worrying about, you'd need to know how large this moment is compared to the natural variation, stroke to stroke, that people produce anyway.

Anonymous

I understand the maths presented, but in practice there is no discernible wiggle in an eight for a cox to correct, and it would in any case be impossible to use the rudder productively to do so. The same is usually true of a four as well, although obviously in a pair the asymmetry is more significant and the turning effect can be more pronounced. I also don't understand what is meant by the rowers in a coxless boat trying to cancel out any wiggle by 'counter sideways movements'. What movements?

I think this is generally more of a theoretical problem than a real one. What we can be sure of is that if the various rigs advocated here conferred any material advantage in practice, every crew would be using them. (Which they don't.)

Anonymous

The notions of wiggling are slightly off, but the principle is valid. Any rig other than those proposed above will cause the boat to turn slightly through the stroke. In particular, since the optimal set up for each rower has them doing more work ahead of the pin, there is a net turning force, which the cox will have to cancel out either with the rudder (which wastes power) or pressure calls (which would either wear out one side (typically strokeside) or 'underuse' the other side). Even in the first case, even though no one would notice the wiggle and could allow it to simply cancel out between the start and end of the stroke, there would still be a slight, avoidable, wiggle, which would waste power (albeit a very small amount) through extra loses from the fin.

As for the advantage, enough crews use these rigs for them to be worthy of consideration. However, this analysis assumes that the crew is perfectly matched. If not, these 'perfect rigs' would need (new) steering corrections to compensate for stroke/bow imbalance, defeating the point of the exercise. Also, having a two+ seat gap between blades on one side may make it harder for a 'sub elite' crew to maintain a good rhythm/pass it down the boat. And we can't forget good old fashioned tradition.

There are also mechanical issues with some of these rigs; the sideways forces are transmitted to the hull, which it must bear. By having 2 or more oars in a row on one side, these forces are proportionately magnified, which I'm guessing would hasten the weakening of the hull. In the case of wing rigged boats, the most pressing issue is practical. In my experience of wing rigged boats, 'symmetrical pairs' (middle pair, outer pair and so on) of riggers are of the same width to match the width of the saxboard at their station, thus only riggers within pairs can be swapped. Thus orthodox bow and stroke riggers are possible; other 'wiggly rigs' are possible (eg. ssbb); but frig rigging would require an extra pair of riggers, at least in a 4 (although it would appear that 'rig d' would be possible...)