Mathematical mysteries: Transcendental meditation

New numbers from old

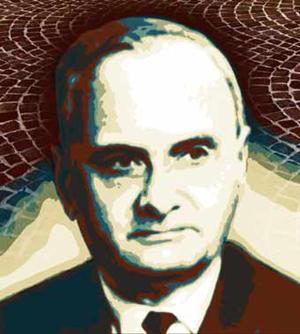

Leopold Kronecker

Nineteenth-century German mathematician Leopold Kronecker once said

"God created the integers, all the rest is the work of man,"

We make rational numbers from the integers by allowing division by integers other than zero. Rational numbers were all the Greeks allowed (in fact, they didn't allow negative quantities to stand on their own, so really they only worked with positive rationals). This left them confused - and sometimes frightened - when geometric results such as Pythagoras' Theorem seemed to imply that rational numbers weren't enough.If you use Pythagoras' Theorem on a right-angled triangle with the two shorter sides of length 1 unit, you quickly realise that the square of the length of the hypotenuse is 2. So what is the length of the hypotenuse? Well, it's $\sqrt{2}$ - but what fraction is that? The answer is that it isn't one - $\sqrt{2}$ is an irrational number, that is, one that can't be represented by any fraction of two integers. Modern-day mathematicians call the rational and irrational numbers together the real numbers, and if all you want to do is to talk about lengths, they are all you need. We can think of real numbers as something we get from rationals by taking limits of infinite sequences - for example, a non-terminating decimal is the limit of all of its finite decimal approximations.

The square root of 2 is irrational

The first thing you might ask if you saw this definition is - are there any irrational numbers? How do we know that $\sqrt{2}$, say, is irrational? To prove that $\sqrt{2}$ is irrational, suppose the contrary, namely that it is rational, so that there are integers $p$ and $q$ such that $$(p/q)^2 = 2.$$ We can also assume that $p$ and $q$ are mutually prime, that is, that they have no common divisors. Then $p^2 = 2q^2$ so that $p^2$ is divisible by 2. This means there is another integer $s$ such that $$p^2 = 2s.$$ Now suppose $p$ is odd. Then $p=2r+1$ for some integer $r$. Substituting into the formula for $p^2$ and multiplying out we see that $$ p^2 = (2r+1)^2$$ $$4r^2 + 4r +1 = 2s. $$ But this isn't possible, because the right hand side is odd, but the left hand side is even. This contradiction means that $p$ is even, so it can be written as $p=2r$ for some integer $r$. Substituting into the formula $$(p/q)^2 = 2,$$ we get that $$(2r/q)^2 = 2.$$ Dividing across by 2, this means that $$2r^2 = q^2,$$ so $q^2$ is even, and $q$ is even (just as we could prove $p$ was). But this is a contradiction, because we assumed $p$ and $q$ had no common factors. This contradiction means that $\sqrt{2}$ is not rational.

Algebraic and Transcendental numbers

Although $\sqrt{2}$ is irrational, it is the solution of a very simple equation, namely $$x^2=2.$$ Numbers like $\sqrt{2}$, which are the solutions to polynomial equations with integer coefficients, are called algebraic, and although an algebraic number may be irrational, it can still be thought of as simple in some sense. But there are numbers which are the solution of no such equation, and such numbers are called transcendental. Since rational numbers are clearly algebraic, the real numbers can be divided into two sets - the algebraic numbers and the transcendental numbers. It is remarkably hard, and may even be impossible, to tell whether a certain number is algebraic or transcendental. It is known that the two most famous irrational numbers, $\pi$ and $e$, are both transcendental. The fact that $\pi$ is transcendental means that one of the most famous problems of antiquity - that of squaring the circle - can never be solved.Squaring the circle

The problem of squaring the circle is to find a construction, using only a straight-edge and compass, to give a square of the same area as a given circle. Since doing this would amount to finding a polynomial expression for $\pi$, the transcendentality of $\pi$ means that it isn't possible.

Ferdinand von Lindemann

The result was proved in 1882 by German mathematician Ferdinand von Lindemann - but amazingly amateur mathematicians have continued to produce fallacious "proofs" that the circle can be squared to this day!

Some of the most bizarre attempts have involved proposing a different and rational value for $\pi$, which would of course be useful if we could do it, but naturally there would be consequences for the rest of mathematics. In 1897, the Indiana State Legislature almost went as far as legislating to set the value of $pi$ equal to 3! The bill was never actually passed, but it came within a

hair's breadth of becoming law.

Long before $\pi$ was finally proved to be transcendental most learned societies had stopped considering circle-squaring arguments sent to them - even though proof of its impossibility was lacking, most professional mathematicians thought it would never be done.

Sums and Products

Despite the fact that $\pi$ and $e$ are now both known to be transcendental, it is still not known whether $\pi+e$ and $\pi \times e$ are. It is known that at least one of them must be, but it is not known which.

Aleksandr Gelfond

Surprisingly, it is quite easy to prove that $e^{\pi}$ is transcendental. This follows from a theorem proved by two mathematicians, Aleksandr Gelfond and Theodor Schneider independently in 1934. The Gelfond-Schneider Theorem says that if $a$ and $b$ are algebraic, $a$ is not 0 or 1, and $b$ is not rational, then $a^b$ is transcendental. We use probably the most famous result in all of mathematics, Euler's formula $$ e^{i\pi}=-1.$$ Taking both sides to the power $-i$ gives $$ (-1)^{-i} = (e^{i\pi})^{-i} = e^{\pi}. $$ Since the theorem tells us that the left hand side is transcendental, it follows that the right hand side is too. It also follows that $e\times\pi$ and $e+\pi$ are not both algebraic, because if they were, then the equation $$ x^2+(e+\pi)x+(e\times\pi)=0 $$ would have roots $e$ and $\pi$, making both numbers algebraic. Of course, this proof doesn't tell us which of $e\times\pi$ and $e+\pi$ is transcendental, or suggest any way to solve the mystery.

For more about this most mysterious number, have a look at Pi not a piece of cake in the news section of this issue of Plus.

About the author

Helen Joyce is editor of Plus.

Comments

Andrew Irving

This is such a lovely article - really enjoyed reading it.

Leslie.Green

The fact that half of all possible rational numbers have a value less than one is a remarkably beautiful observation.

http://lesliegreen.byethost3.com/articles/density.pdf