Light weight

Does light have weight? Newton thought so. He supported the corpuscular theory of light, regarding it as comprised of particles with small but finite mass. He concluded that such particles would be influenced by a gravitational field. So, using his laws of motion, we can calculate how gravity would bend such a light beam.

Curving paths

It is a surprising fact that the motion of an object orbiting a massive body such as the Sun is independent of the mass of the object. By Newton's laws, the motion is governed by the equation $$ m a = \frac{G M m}{r^2} $$

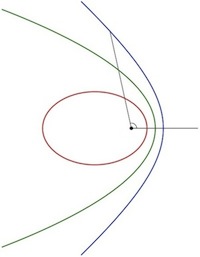

The red orbit is elliptical, the blue orbit is hyperbolic. In between, the green orbit is parabolic. (Image by Stamcoe CC BY-SA 3.0)

where $m$ is the mass of the object, $a$ is the magnitude of its acceleration, $M$ the solar mass, $r$ the distance (this distance is measured between the centres of the Sun and the object) and $G$ is Newton's gravitational constant. The mass $m$ on the left and right side of this equation cancels out, so the motion does not depend on the mass of the object.

Let's start by considering an asteroid approaching the Sun from a great distance. From Newton's laws we can calculate that if the asteroid's kinetic energy is small the asteroid will be captured by the Sun's gravity and it will follow an elliptical orbit, returning repeatedly to its initial position. We'll assume that the asteroid is approaching the Sun with high energy, so that it traces out a hyperbolic orbit, passing by the Sun once, never to return. This orbit has the equation $$ \frac{x^2}{a^2} - \frac{y^2}{b^2} = 1 $$ where the $x$ and $y$ coordinates refer to the position of the asteroid in the plane that contains its trajectory (the hyperbolic orbit) and the Sun. The real numbers $a$ and $b$ are called the semimajor and semiminor axes; these define the shape of the hyperbola.

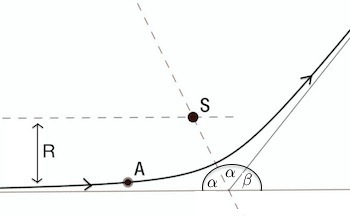

The trajectory of an asteroid (at point A) moving past the Sun (at point S) on a hyperbolic orbit.

When the asteroid is far from the Sun it moves with speed $V$ along a trajectory that is very close to a straight line (the asymptote of the hyperbola), shown as a horizontal line in the image on the right. We'll write $R$ for the shortest distance from this line to the Sun (called the perpendicular distance). The kinetic energy of the asteroid (per unit mass) is given by the usual formula $E = \frac{1}{2} V^2$.

The angular momentum is the linear momentum, $mV$, multiplied by the perpendicular distance to the Sun, $R$. When the asteroid is at a great distance from the Sun, this is $L = RmV$ or, per unit mass, $L = RV$. As the asteroid moves closer to the Sun, its path is curved by the Sun's gravitational field. Its velocity and momentum change, but its angular momentum is conserved.

These quantities $E$ and $L$ can also be expressed in terms of geometric parameters, the major and minor semiaxes $a$ and $b$ of the hyperbolic orbit: $$ L^2 = \frac{G M b^2}{a} $$ and $$ E = \frac{G M}{2 a}. $$ (You can find the proofs for these results in many text-books on orbital dynamics (for example Classical Mechanics by R. Douglas Gregory).

We can use these expressions to deduce the amount by which the Sun deflects the asteroid from its initial path, the angle $\beta$ in the figure above. By the geometry of hyperbolas the semi-angle $\alpha$ of the hyperbolic orbit (see the figure above) is given by $$ \tan \alpha = \frac{b}{a}. $$ We can rearrange and combine the above equations for the energy and momentum to rewrite this as $$ \tan \alpha = \frac{b}{a} = \frac{R V^2}{G M}. $$ The angle of deflection is $\beta = \pi - 2 \alpha$ which, thanks to the trigonometric identity $\tan(\pi/2 - \theta)=\cot(\theta) = 1/\tan(\theta)$, is $$ \tan \left(\frac{\beta}{2}\right) = \frac{1}{\tan \alpha}. $$ We can rewrite this as $$ \tan \left(\frac{\beta}{2}\right) = \frac{a}{b} = \frac{G M}{R V^2}. $$ The tangent of a small angle is very nearly equal to the angle itself. So, since $\frac{\beta}{2}$ is a very small angle, we can replace the tangent $\tan \left(\frac{\beta}{2}\right)$ by its argument $\frac{\beta}{2}$ to give $$ \beta = \frac{2 G M}{R V^2}. $$ And thus we have a formula for the deflection of the asteroid by the gravity of the Sun.

Note that the mass of the asteroid does not influence its trajectory. The deflection angle $\beta$ is the same for all bodies with the same values for $R$ and $V$. If light is endowed with mass, as Newton thought, we set $V = c$, the speed of light, and obtain the bending angle for a ray of light: $$ \beta = \frac{2 G M}{R c^2} . $$ Assuming that the light ray passes close to the Sun, we take $R$ to be the solar radius. Using values (all in SI units) for the universal constant of gravitation $G = 6.67 \times 10^{-11}$, the solar mass $M = 2 \times 10^{30}$, solar radius $R = 7 \times 10^8$ and the speed of light $c = 3 \times 10^8$, this gives $$ \beta \approx 0.423 \times 10^{-5} \mbox{radians} = 0.87 \mbox{arc seconds} $$ So Newton's theory of gravity predicts that the path of a light ray passing close to the Sun will be bent by an angle of 0.87 arc seconds.

Putting it to the test

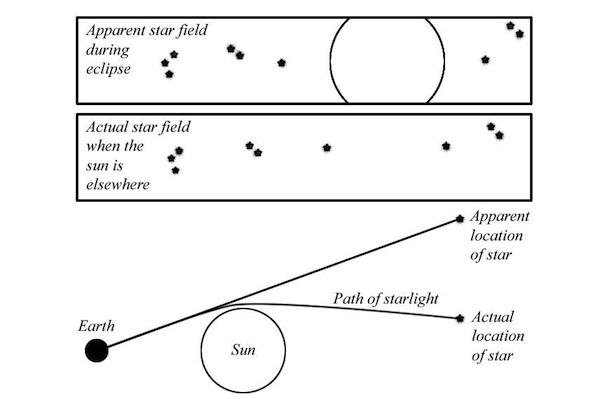

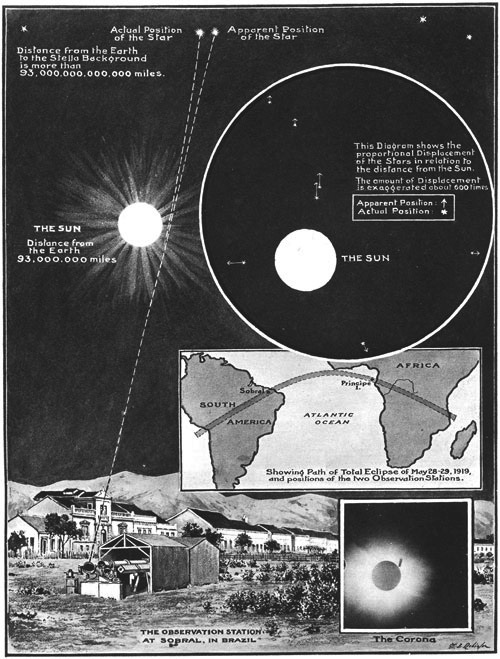

A remarkable series of observations during the solar eclipse in May 1919 confirmed that light passing close to the sun is deflected by its gravitation. A star near the edge of the Sun appears to be slightly further away in the sky from the Sun when compared to its position when the Sun is absent. This effect is observable during a total eclipse: photographs of the sky are compared with photographs of the same region when the Sun is elsewhere and a difference in the apparent positions of the stars can be seen.

The actual path of the light from a star as it is bent by the Sun, and the apparent position of the star as a result (Image NASA)

Albert Einstein had recently discovered the general theory of relativity and his theory also predicted the Sun would deflect the path of light. According to this new, and at the time, not-widely-accepted theory, the distortion of spacetime due to the presence of the massive Sun resulted in a bending angle of $$ \beta = \frac{4 G M}{R c^2} \approx 0.847 \times 10^{-5} \mbox{radians} = 1.75 \mbox{arc seconds}, $$

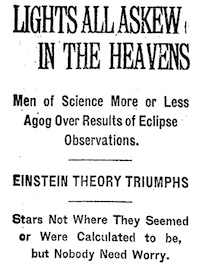

Headlines about the results in the New York Times in 1919

twice the value of the deflection angle predicted by Newton's laws. This is a small angle but it was well within the then-current techniques of astronomy. The stage was set to put the two theories to the test.

Two expeditions set out from Britain, one to the Isle of Principe off Africa, the other to Sobral in northern Brazil, both on the path of totality of the eclipse. Sir Arthur Eddington, who took part in the former expedition, described the observations and conclusions (you can read his report on the expedition and find our more from Cosmic Times). The observations at Principe gave an estimated deflection of 1.61+/−0.30 arc seconds, in excellent agreement with Einstein's prediction. The Sobral results provided further confirmation. The astronomical observations in Principe and Sobral could not be reconciled with Newton's theory, and a scientific revolution ensued. This experiment catapulted Einstein into world fame and he has remained an icon of science ever since.

The illustration to accompany coverage of the eclipse in the 22 November edition of the Illustrated London News

About this article

Peter's mathematics blog is at thatsmaths.com.

Comments

Anonymous

I will avoid the obvious pun that of course it has no weight: it's light!

But inasmuch as "weight" is dependent on the existence and magnitude of an external gravitational field, would not the correct term be "mass"?

Anonymous

So?

Does it?

Or does it not?

Gary Courtney

You have written in regard of Einstein's theory "The observations at Principe gave an estimated deflection of 1.61+/−0.30 arc seconds, in excellent agreement with Einstein's prediction. The Sobral results provided further confirmation. The astronomical observations in Principe and Sobral could not be reconciled with Newton's theory, and a scientific revolution ensued."

This does not accord with my understanding of what happened. The results from Sobral were closer to Newton's predictions (half the deflection angle of Einstein's) but the discrepancy was later attributed to defects in the Sobral telescopes.

The bending of "space-time" *might* explain why a passing photon or comet's pathway would be deflected, but it goes not explain why a stationary (relative to the earth) object should fall towards the earth.