Crime fighting maths

Fighting crime — perhaps not the first thing that springs to mind when you think of maths. Ask someone on the street what they think about maths and unfortunately their answer may well be:"Maths is boring", "Maths is exact", "Maths is irrelevant", or even "Maths is scary".

Does this scare you?

Apart from the last point, maths may seem very different from the confused, unpredictable and highly relevant business of fighting crime. But in fact maths is very relevant. It is integral to many of the methods police use to solve crime, including dealing with fingerprints, accident and number-plate reconstruction and tracking down poison.

Challenges facing the police

Police are faced with many challenges when tackling a crime. They must find out what happened at the scene of the crime or accident. They need to interpret confusing data which also needs to be stored and mined for information. And in the interests of justice the evidence, both physical and electronic, must be kept secure.

Mathematics can help with all of these. Data can be stored and interpreted using wavelets, probability and statistics. It can be securely transmitted using prime numbers and cryptography. But first of all, police must get at the information underlying the data. They must look at all the evidence left at the a crime scene and work backwards to deduce what happened and who did it. Often, the evidence is a result of a physical process that is well understood — like a speeding car causing skid marks. So to find out the exact cause of the evidence — the speed of the car — the maths that describes the physics needs to be run backwards. This is called solving an inverse problem, and in this article we will explore three examples of how it is done.

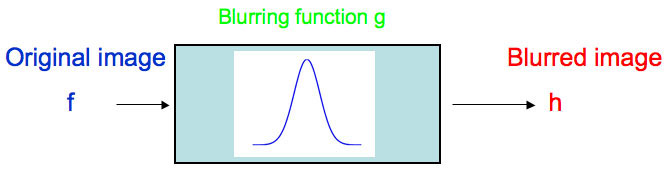

This blurred fingerprint is all the |

Running the blurring process backwards, |

What happened at a crime or accident given the evidence?

[Image from NASA]

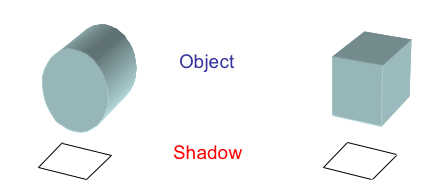

Inverse problems are mathematical detective problems. An example of an inverse problem is trying to find the shape of an object only knowing its shadows. Is it possible to do this at all? What sort of errors are we likely to make, and how much extra information is needed?

To solve an inverse problem, we need a physical model of the event — we need to understand what causes lead to what effects. Then, given the known effects, we can use maths to give the possible causes, such as deciding what shaped objects cast the shadows in this photo.

We also use maths in this situation to establish the limitations of the model and accuracy of the answer. In the example of shadows cast by objects, different causes (different shaped objects) may give very similar effects (cast similar shadows)!

Other examples of inverse problems are remote sensing of the land or sea from satellite images, using medical images for diagnosing tumours, and interpreting seismographs to prospect for oil.

Mechanics fights crime

Let's step into an ordinary day in the life of a police unit and see how mathematics can help fight crime. First up, we are investigating a car accident and need to answer the question: was the car speeding?

The evidence available is the collision damage on the vehicles involved, witness reports, and tyre skid marks. Just like on television, examining the skid marks can help reconstruct the accident. The marks are caused by the speed of the car as well as other factors such as braking force, friction with the road and impacts with other vehicles.

Mathematically we can use mechanics to model this event in terms of $s$, the length of the skid, $u$, the speed of the vehicle, $g$, the acceleration due to gravity and $\mu$, the coefficient of friction times braking efficiency. The model links the cause (the speed of the car) to the effect (the distance of the skid): $$ s=\frac{u^2}{2\mu g} $$ This can be rearranged so that given the skid distance we can mathematically determine the speed of the car, usually giving a lower bound: $$ u=\sqrt{2\mu gs} $$ But for this to work, we need to have an accurate estimate of $\mu$, the value describing friction and braking efficiency!Where is the poison?

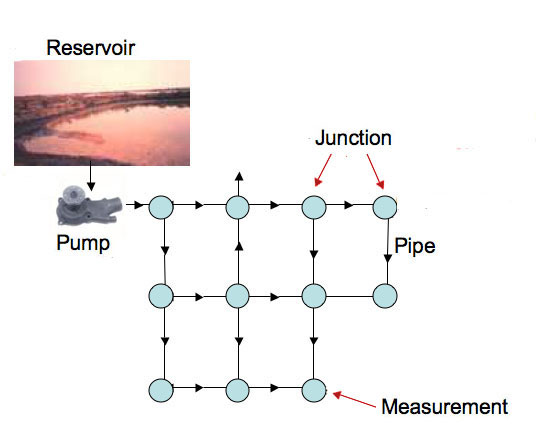

Meanwhile, somewhere a contaminant has been illegally released into the water network. Some time later, when the police have been alerted to the contamination, can we find where it was released?

The water network

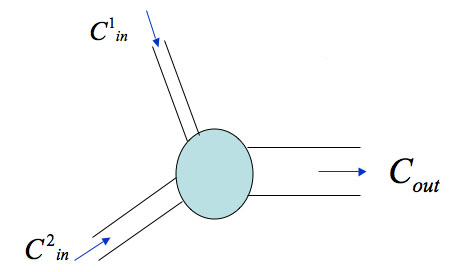

The solution from two pipes is mixed at the junction to give a new concentration of the contaminant.

To reconstruct what is happening in the water network, we need to find the flow rates in the pipes and measure the present contaminant concentrations at the junctions. Then we can make a guess at the initial contaminant concentrations (at each junction), and flow the model forward in time and compare it with what we measure now in the real network. Using a process called nonlinear optimisation, we can adjust the initial concentrations until the present concentrations predicted by the model agree with our measurements.

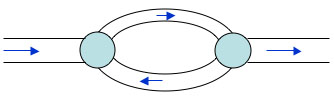

A circulation path in the network means that we can

only come up with several possible causes for the

contamination.

For a simple pipe network we can solve the model for a single possible cause — and find exactly where in the network the poison was released. However, for more complex networks where there are circulation paths, we may come up with several possible possibilities for how the network was contaminated.

Catching the getaway car

Meanwhile, across the other side of town, someone has robbed a bank. Although he escaped in a getaway car, he was pursued by police. The good news is the police managed to take a photo of the number plate of the car, but the bad news is that the photo is blurred.

Simulated original |

Blurred photograph |

The deblurred image

Crime might not pay, but maths does!

So the neat tricks TV cops use, such as deblurring number plates and reconstructing accidents from skid marks, are not as far fetched as they seem. In the fight against crime for both TV cops and the real police force, the secret weapon is mathematics.

About the author

Chris Budd is Professor of Applied Mathematics at the University of Bath, and Chair of Mathematics for the Royal Institution. He is particularly interested in applying mathematics to the real world and promoting the public understanding of mathematics.

He has recently co-written the popular mathematics book Mathematics Galore!, published by Oxford University Press, with C. Sangwin.

Comments

Anonymous

Very helpful :)

Anonymous

Thank You

Anonymous

It's the first time I've came to a page that actually explained in a form of english that a 15 year such as myself can understand, so thanks for not making me have to look up every second word :)

Anonymous

This was helpful for a project - however, for the blurring function, what are the values of y and d?

Anonymous

correct me if I'm wrong but "y" is a variable, the d is supposed to represent a differential amount of "y" because that is an integral and usually they tell you what variable you integrate with respect to. In fact I believe that equation is a convolution between the function f and g which is essentially the operation you perform when applying a blurring function. That brings me to a question myself that is, why is the dy raised to the power of 2?

Nba2k976

How do you find the blurring function or (g). Is it a part of a program, or seperate process, or should i just know these things?