We know that there are shapes in the plane whose outline is incredibly crinkly. Examples are fractals, like the famous Mandelbrot set. But just how complex can a shape be?

One concept that captures some of a shape's crinkliness is

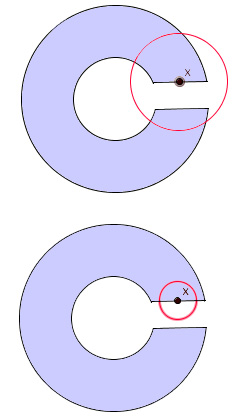

local connectivity, or rather a lack of it. To understand local connectivity, first think of a comparatively simple shape, like the one in the picture on the left (call it $S$). Pick a point $x$ that's part of $S$ — for illustration we'll pick one that lies on its outline. Now draw a little disc $V$ with $x$ at its centre and look at the intersection of $S$ and $V.$

As you can see in the picture, it may happen that the intersection consists of more than one

connected component. In our example this happens because the outline of $S$ curves around and re-enters the disc $V$ again at a place away from $x.$ However, that's only because we chose $V$ to be quite large. By making $V$ smaller we can ensure that the intersection of $S$ and $V$ consists of only one connected component. A shape $S$ (drawn in the plane) is

locally connected at $x$ if the intersection of a disc $V,$ centred at $x,$ and $S$ consists of a single connected component for all discs whose radii are small enough.

A shape $S$ is locally connected if it's locally connected at all its points. All the obvious shapes you can think of — circles, squares, triangles — are locally connected. (The formal definition for a general topological space $S$ is that $S$ is locally connected if for all points $x$ in $S$ and open neighbourhoods $V$ of $x$ there is an open connected neighbourhood $U$ of $x$ that's contained in $V$.)

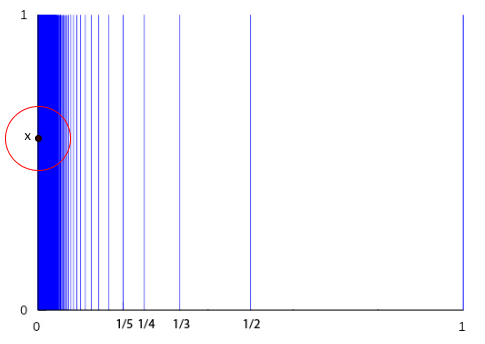

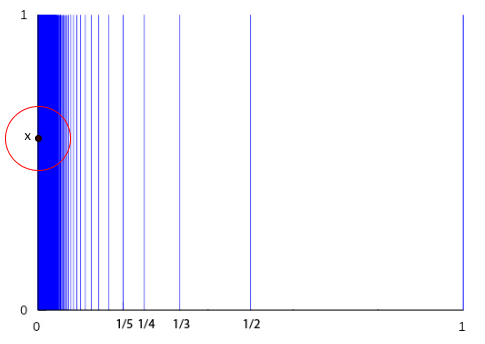

How can a shape not be locally connected? An example is the

comb space. Think of the closed interval $[0,1]$ (closed means it contains its endpoints). Now at every point of the form $1/n$ where $n$ is a natural number, erect a vertical spike of length 1. Also include such a spike at the left-most point of the interval $[0,1],$ that is, at the point $0.$ So we have vertical spikes at $1,$ $1/2,$ $1/3,$ and so on.

Now pick a point $x$ somewhere on the left-most vertical spike (but not at the point where that spike meets the horizontal interval) and look at any disc $V$ small enough to not contain any piece of the horizontal interval. Since there are infinitely many points of the form $1/n$ arbitrarily close to $0$ on the horizontal interval, the disc $V$ will contain a piece of each of these infinitely many separated vertical spikes. That's true no matter how small $V$ is, so the comb space is not locally connected at any point $x$ on the left-most vertical spike.

So is our favourite fractal, the Mandelbrot set, locally connected? The answer is that we don't know. Mathematicians believe that it is, and they have been able to show that it is locally connected at many of its points – but they haven't been able to prove that it's locally connected at all of them.

Comments

Anonymous

Very interesting read, especially considering I'm struggling with a somewhat related problem: contour offsetting (contour and not polygon because it can include arcs). Eliminating a section from between its neighbours as it shrinks away to nothing would be doable, but the problem is you never know when some other, non-local section of your contour starts interfering with the section you're trying to offset and each-with-each gets rather daunting, fast. For a poor code monkey like me it can all be a bit overwhelming... :)

Anonymous

The question can be stated as to which rate of change is the faster one. Is the rate of shrinkage of the contour or of the continuation loop (circle) the greatest.

If they are related, then the connectivity is zero because the RATE of shrinkage of the fractal (and of the comb too) depend inversely on the size of the previous change which is a logarithmic variation, whilst the rate of change of the continuation loop is a reciprocal one. Then connectivity is zero for both cases.

However if these two changes are arbitrary or unrelated, there is no answer.