The gambler's ruin

Imagine you're a gambler and someone proposes to play the following game. You start with a fortune of £1. You then flip a fair coin.

- If it lands heads-up you gain £1

- If it lands tail-up you lose £1

You continue to flip the coin, gaining or losing a pound with each toss. If you go broke the game ends. As long as you don't go broke, you keep on playing indefinitely, potentially amassing a huge fortune.

Should you accept to play the game?

An infinity of ways

To find out, let's try to figure out the probability that you eventually end up broke. First note that there are an infinite number of ways in which this could happen.

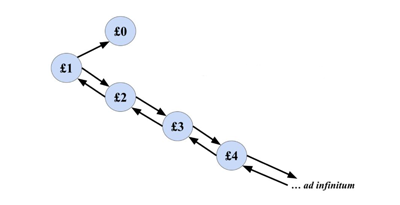

On your very first toss of the coin, you could lose your £1, immediately rendering yourself broke.

Alternatively you could gain £1 on your first toss before losing £2 on the two subsequent tosses.

Or you could gain £2 on your first two tosses before losing £3 on the three subsequent tosses.

More generally, if you gain £$n$ on your first $n$ tosses and then lose £$(n+1)$ on the subsequent $n+1$ tosses you will go broke.

This already gives you an infinite number of heads and tail sequences that mean you end up broke. But there are even more ways. That's because you may also end up first increasing your fortune, then decreasing it but not all the way down to zero, then increasing it again, etc, before your fortune finally drops down to zero and you're broke.

Your first turn will either leave you broke or with £2. After that anything can happen...

On the up-side, you may also end up never going broke at all. Your fortune could even end up approaching infinity (you wish).

Considering each unique way of ending up with £0 is impossible, simply because there are infinitely many sequences of heads and tails that can make this happen. So let's encompass all the possible "routes" from £1 to £0, and their respective probabilities, in $p$. Let $p$ be the probability that, starting from £1 you eventually end up with £0. The probability $p$ is the number we are interested in finding.

Universal p

Now, the probability of going broke after your first turn is $1/2.$

However, after your first turn it is equally probable that you could have risen from £1 to £2. From £2 what then is the probability of going broke? Going broke from £2 would require you to first get from £2 down to £1. (Whatever route we take from £2 to £0, we will inevitably end up at £1 along the way.) Now if a sequence of heads and tails gets you from £2 to £1, then the same sequence of heads and tails would also get you from £1 to £0, and vice versa. The starting and end points of the journey determined by the coin tosses would simply be shifted along by a distance of 1. This means that the probability of eventually going from £2 to £1 is the same as the probability of eventually going from £1 to £0. That probability is $p$.

The same reasoning works more generally. The probability of going from £$(n+1)$ to £$n$ is equal to $p$ for all positive integers $n.$ The probability $p$ is universal in this way.

This means that the probability of dropping from £2 to £1 and then from £1 to £0 is $ p \times p = p^2$. Therefore, the probability of eventually going broke, starting with £1 and first going up to £2 is $1/2 \times p^2.$ That's because:

- The probability of going up to £2 from £1 is $1/2$

- The probability of going from £2 to £0 is $p^2$

Now the probability of going broke at all is the probability of going broke at the first toss of the coin (which is equal to $1/2$) plus the probability of going broke after first having gone up to £2. In other words,

$$P(\mbox{going broke at all})= 1/2 + 1/2 p^2.$$

But wait a second... Haven't we just found two expressions for the same thing? One the one hand, the probability of going broke at all, starting from £1, is equal to $p$. But on the other, as we have just shown, it is also equal to $1/2 + 1/2 p^2.$

Since these two expressions are equal, we can form the equation $$p=1/2+1/2 p^2.$$ Multiplying through by $2$ gives $$2p=1+p^2.$$ Bringing all terms over to the right hand side gives $$0=1-2p+p^2=(1-p)^2.$$ Solving this equation for $p$ gives $p=1$. This means that the probability of eventually going broke is 1.

What does this mean?

You'll almost surely lose all of these...

Usually, if something has a probability of 1 this means that it's guaranteed to happen: no other outcome is possible. So does our result mean that you going broke is the only possible outcome of this game? Clearly not. For example, it is theoretically possible that you only ever toss heads, thereby steadily increasing your fortune. It is also possible for your fortune to go up and down forever, without ever decreasing enough to go broke.

To see what's going on, notice that you can imagine playing the game against an opponent: if heads comes up your opponent gives you £1 and if tails comes up you give the opponent £1. To ensure that the game only stops when you go broke, your opponent needs to have infinite wealth.

You can also imagine playing the game against an opponent who only has finite wealth to start with. In this case the game ends when you go broke, or when your opponent goes broke, whichever happens first. It is possible to show that in this situation someone definitely will eventually go broke. In other words, the game can't go on forever without anyone ever hitting £0. Intuitively, it seems clear that, the larger your opponent's initial fortune, the higher the chance that you go broke first, and the lower the chance that your opponent goes broke first.

This is indeed the case. If you start with £1 and your opponent with £$M$, for some natural number $M$, then the probability of you going broke is

$$\frac{M}{M+1},$$ and the probability of your opponent going broke is $$\frac{1}{M+1}.$$

If $M$ is a very large number, then $\frac{M}{M+1},$ is very close to 1 and $\frac{1}{M+1}$ is very close to 0. In fact, if you increase your opponent's wealth towards infinity, the probability of you going broke converges to 1, and the probability of your opponent going broke converges to 0. That's the situation we considered in this article.

This phenomenon, that an outcome can have probability 1 but still not be the only outcome that can occur, can happen in situations where infinity is involved. Mathematicians say the outcome occurs "almost surely", or "almost certainly" in this case. Such situations don't occur in real life: we are always dealing with finite amounts of time or space, and a finite level of precision. It's amazing, though, that mathematics allows us to think through these hypothetical situations.

The game we have played is an example of something called gambler's ruin in action. The gambler's ruin is a thought experiment which, as the name suggests, looks at games where a gambler is (almost) sure to go broke, even though it's not at first obvious that's the case.

About this article

Maryam Naheem

Maryam is a final year student at the Tiffin Girls’ School in Kingston Upon Thames. She enjoys mathematical problem solving, created a school Maths Journal to share fun mathematical ideas with other students, and is looking forward to studying Maths at university.