The longitude problem

In Latitude by the stars we saw how a little geometry helps adventurous seafarers to work out their latitude. People have been using the stars to do this for millennia. But longitude is a different story. It wasn't until the eighteenth century that people found a way to reliably measure longitude, and the fact that they couldn't do so earlier has lost countless lives at sea. The solution to the problem was eventually delivered by a clock.

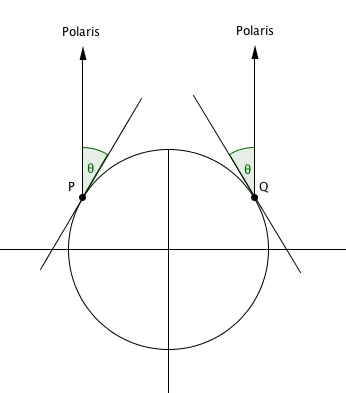

Latitude can be measured using the position of Polaris above the horizon because that position changes as you move North or South, that is, as you vary your latitude. For longitude this isn't the case: the position of Polaris does not change as you move East or West, varying your longitude. You can see this in the two-dimensional picture below. The points $P$ and $Q$ lie on different meridians, but the angles arising from Polaris' position are the same.

John Harrison (1693-1776).

This seems easy today, but until not that long ago it was a huge problem. The clocks that existed were too sensitive to be taken on a ship: the rocking and rolling would make them inaccurate. Sailors' inability to determine longitude had disastrous consequences. An example is the Scilly naval disaster of 1707 in which four British ships sunk just off the Isles of Scilly, tantalisingly close to their home port of Portsmouth. Because sailors could not work out their exact position, and with a little help from bad weather, the ships struck rocks, resulting in the death of up to 2,000 men and one of the worst naval disasters in British history.

Several nations, including the Dutch and the Spanish, had already offered prizes to anyone who could solve the longitude problem, and in 1714 the British followed suit, offering a massive (at the time) £20,000. All sorts of solutions had been proposed. One involved carrying a wounded dog on board ship which, due to a mysterious alchemical treatment, would howl every time it was noon in Greenwich. Others were more scientific. For example, comparing the position of the Moon against the other stars and then consulting a detailed catalogue of stars makes it possible to determine the local time with a fair degree of accuracy. The method is time consuming, however, and prone to errors.

It was a working class joiner from Lincolnshire who finally won the Longitude Prize. From 1730 onwards John Harrison worked on maritime clocks, the last two of which were accurate enough to win the prize. Claiming the prize, however, was a long struggle, as the Longitude Board stubbornly refused to hand it out in full. It took an appeal to King George III and then to Parliament to set things right. "By God, Harrison, I will see you righted!" is what King George is said to have exclaimed, and Harrison finally received the remaining money, as well as the recognition he deserved, in 1773. He died three years later on his 83rd birthday.

The story of the longitude problem is beautifully described in the book Longitude by Dava Sobel.