Sex, evolution and parasitic wasps

Sometimes a state of affairs becomes so familiar to us that it is simply expected, and we may forget to wonder why it should be that way in the first place. Sex ratios are a good example of this: the number of men and women in the world is roughly equal, but why should this be the case?

Many mammals have an equal sex ratio at birth.

For many 18th century thinkers the answer lay in divine providence – the goodness of God – and the equal number of boys and girls born each year was seen as an endorsement of monogamous marriage written into the very laws of nature. This changed with the publication of Charles Darwin's Origin of Species in 1859, followed by The Descent of Man in 1872, and the focus began to shift to finding an explanation in terms of evolution and natural selection. Darwin made an attempt but quickly withdrew it, concluding that "the whole problem is so intricate that it is safer to leave its solution for the future".

This solution was to come in the 20th century. The reason why most species produce roughly equal numbers of male and female offspring is actually very simple, so let's see how maths can be used to prove an intuitive biological argument.

Fisher's principle

It's disputed whether the great British geneticist Ronald Fisher was really the first to explain why evolution favours equal numbers of sons and daughters but the result still bears his name: Fisher's principle. Begin by considering a diploid species, in which each organism has two copies of each chromosome, one coming from the mother and one from the father. This means that half of each generation's genetic material must come from female parents and half from male parents.

Assume that mating within the population is random. This will mean that each male and female organism can expect to pass on the same quantity of genetic material to the next generation as any other member of the same sex. In practice this probably couldn't happen, but it's a useful model. Now consider a population with more males than females. The total amount of genetic material passed on by the males is equal to that passed on by the females, because each child contains an equal amount of both. Since there are more males, it follows that the expected share for each individual male will be lower than that for each female, and any given female can expect to pass on more genes than any given male.

Ronald Fisher, 1890-1962.

Think of each parent as an investor, looking to get the greatest genetic return on their finite number of children. In the population considered above it's clear that there's a better "payoff" associated with daughters than with sons, so natural selection will favour organisms which go against the population's male bias and produce more female offspring. They will have more grandchildren, and therefore the female-biased sex ratio will become more common until the population has equal numbers of both sexes. Conversely, it pays to have more sons in female-majority populations. The equal sex ratio is thus the only one which can't be beaten by a different strategy and hence is said to be stable.

Notice that we're talking about a stable strategy rather than an optimal one. A population's maximum possible growth is proportional to the number of females, so its members could probably all do better if they universally adopted a somewhat daughter-biased sex ratio. However, natural selection would favour any individual in the population which bucked this trend to produce more sons so this strategy would not be stable. Having half male children and half female may not be the optimum strategy but it is unbeatable: no strategy competing against it can do better so natural selection will favour the status quo.

Proving that 1:1 is the best strategy

These arguments seem fairly convincing, but can it be proved mathematically that equal investment is an unbeatable strategy? Let's begin by defining some terms.

Imagine a population of wasps. Any species would do, but wasps are a nice example as the females of some varieties have the ability to choose the sex of their offspring. Assume each female can expect to have $n$ children, and denote the proportion of these children which are male by $x$ (so $0\leq x \leq 1$). Each female can then expect $nx$ sons and $(1-x)n$ daughters. We'll also assume that mating is random within the population. To prove Fisher's principle, we need to build up a model for the fitness of different reproductive strategies, then show that there's no way to beat the 1:1 ratio. Fitness is a measure of how successful an organism is in spreading their genes through the population, and a good definition for it here is the success of an organism's offspring in producing children of their own. To keep things simple, assume there is one variant female, who can adopt any sex ratio, and a certain number $2p$ herd females who always produce equal numbers of sons and daughters.What will the fitness of each starting wasp be? In words the answer is clear:

$$\begin{array}{ll}\mbox{Fitness}= & (\mbox{Expected no. of daughters}\times \mbox{Expected offspring per daughter}) \\ & + (\mbox{Expected no. of sons} \times \mbox{Expected offspring per son}).$$Note that this answer won't be the same as the number of grandchildren. The assumption of completely random mating includes offspring between siblings, so there'll be some overlap between the offspring of the daughters and of the sons.

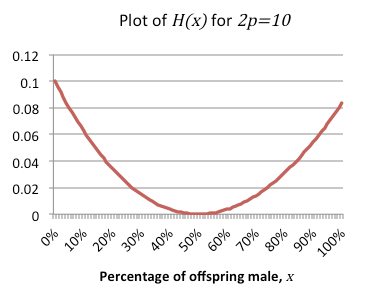

Let's start with the variant wasp and try to put these terms in numerical form. Represent the fitness as a function $f(x).$ We've already defined the expected number of daughters to be $(1-x)n,$ and since each daughter can expect $n$ children we get $$f(x)=(1-x) n^2+\mbox{(Expected no. of sons x Expected offspring per son)}.$$ The number of sons is also easy – it’s defined to be $xn$ – and expected offspring is only slightly trickier. Remember that we're assuming random breeding within the population, so the expected number of children per male (in a particular generation) will be the total number of females (in that generation), multiplied by their expected number of children and divided by the total number of males (in the generation). We can break this down as follows $$\begin{array}{l}\mbox{Expected offspring per son } \\ \mbox{ } = \frac{\mbox{Expected no. of variant's daughters} + \mbox{Total no. of herd's daughters}}{\mbox{Expected no. of variant's sons} + \mbox{Total no. of herd's sons}}\times n. \end{array}$$ We can get the herd values by taking the formulae we've got for the variant's offspring, setting $x=1/2$ (since the sex ratio is even) and multiplying by the number of herd wasps in the population $2p:$ $$\mbox{Total no. of herd' s daughters} = (1-\frac{1}{2})2np=np,$$ $$\mbox{Total no. of herd' s sons} = (\frac{1}{2})2np=np.$$ As expected, the even sex ratio means that the number of sons and daughters are equal. Substituting all of these in gives $$\mbox{Expected offspring per son} = \frac{(1-x)n+np}{xn+np}\times n = \frac{n-xn+np}{x+p}.$$ This is everything needed to write out the formula for the variant wasp’s fitness in full $$f(x)=(1-x)n^2+\frac{nx(n-xn+np)}{x+p},$$ which can be rewritten as $$f(x)=\left(1+\frac{2x-4x^2}{2x+2p}\right)n^2.$$ We’ll also need a formula for the fitness of a member of the herd, which we denote by $g(x).$ This is constructed in exactly the same way, but the number of sons and the number of daughters are replaced by $\frac{1}{2}$. The resulting equation is $$g(x)=\left(\frac{1}{2}+\frac{1-x+p}{2x+2p}\right)n^2.$$ Both $f(x)$ and $g(x)$ are proportional to $n^2.$ This makes intuitive sense, since the number of children one generation down the line is proportional to $n,$ so two generations will be proportional to $n^2.$ However, we're not really interested in the number of offspring per se, only how the expected fitnesses for variant and herd compare to each other and which is greater. Therefore, we ignore the $n^2$ terms and write the formulae $$F(x)=1+\frac{2x-4x^2}{2x+2p},$$ $$G(x) = \frac{1}{2}+\frac{1-x+p}{2x+2p}.$$ With these terms removed the formulae are both independent of $n.$ This shows that the number of offspring an organism produces is irrelevant to the stable sex ratio: whether they can expect 2 children or 2,000 the same rules will apply. If Fisher's principle is correct then the herd's strategy can't be defeated: $F(x)$ can never be greater than $G(x).$ The easiest way to show this is to define a new function representing the difference between the two functions $$H(x)=G(x)-F(x)=-\frac{1}{2}+\frac{1+p-3x+4x^2}{2x+2p}.$$ This can be simplified to $$H(x)=\frac{4x^2-4x+1}{2x+2p}.$$

Except when it isn't

Well, that isn't quite true. Any deduction is only as good as its starting assumptions, and several of the ones used here could be called into question.

A parasitic wasp of the Braconidae family. Image: Richard Bartz.

For now let's focus on just one assumption, that every organism is competing with every other organism in the population. This can be a useful model but it obviously doesn't hold true in reality: a lion in South Africa's Kruger National Park won't be competing with those in London Zoo. Most organisms will only be competing with a relatively small subset of the general population at any one time.

Certain species of wasp take this to extremes. In these varieties several females lay eggs in a food source, such as a paralysed caterpillar, and then die. When the eggs hatch the next generation will feed, grow and then mate indiscriminately with the other wasps hatched in the same source. The females will then leave the host to seek out a new host to lay their eggs in while the males die off.

There are two aspects of this system that need to be taken into account here. The first is the local fitness of different sex ratios: how successful will particular ratios be in the competition between different wasps in one particular food source. The second is the global fitness of a sex ratio: how does the success of a particular strategy compare with the average success of all wasps in the population. If a strategy is fitter than the average across the population, then it will spread.

The earlier proof of Fisher's principle will still hold for local fitness: if a wasp adopts a equal sex ratio then it can't do worse than any of the other wasps who laid eggs in the same food source. The interesting thing is that this doesn't guarantee success on the global level, as doing better than local competitors doesn't necessarily mean doing better than the population average.

This poor caterpillar carries wasp larvae parasytes. Image: Stsmith.

These predictions can be compared to observed sex ratios in nature with encouraging results. There are a number of factors which complicate the idealised model we've constructed here, nudging the actual sex ratio one way or the other, but studies have shown that initially female-leaning sex ratios do move towards 1:1 as the number of wasps per host grows. It's a testament to the power of applied mathematics that, using only a few reasonable assumptions and some A-level techniques, this result could be anticipated years before it was demonstrated experimentally.

About the author

Paul Taylor is studying towards an MSc in Biomathematics at Durham University where he previously read maths and philosophy as an undergraduate. In his spare time he plays Go and writes about science for student media.