Maths in a minute: Cellular automata

The name "cellular automaton" may sound a bit frightening, but the concept is actually quite simple. Think of a grid on the plane, for example a square grid or a honeycomb, in which each individual cell (each little square or hexagon) has one of two colours, say black or white. At each time step (say every second or every minute) the cells change colour in a way that depends on what colour the neighbouring cells are.

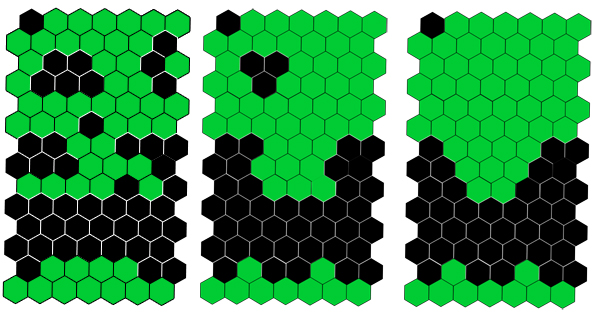

For instance, in the honeycomb example above, which shows only three states separated by two time steps, a cell changes colour if at least four of its neighbours are the opposite colour. You could carry on evolving the grid indefinitely, changing the colours according to the rules at each time step.

More generally, cellular automata can be defined in any dimension (you could have just a one-dimensional row of cells, or a three-dimensional grid of cells, for example), they can involve more than one colour, and they can also involve an element of chance.

Cellular automata are capable of amazingly complex behaviour. Even simple rules can give us patterns that evolve chaotically, leaving us no hope of ever predicting them accurately. But they can also produce stable patterns that change little over time, or patterns that look like they couldn't possibly be the result of mindless interactions between neighbours, but involve some grand overall design (technically, cellular automata can exhibit self-organisation and emergence).

The video below shows the evolution of a cellular automaton in which the individual cells are so small, you can hardly see them (they're like the pixels on a computer screen). You can see how spiral patterns emerge over time. These actually resemble spiral patterns found in nature. Find out more in the article Spontaneous spirals by Wim Hordijk, who also made the movie.

Cellular automata are used to simulate processes in nature (for example the pattern formation on animal skins). Theoretical computer scientists like them because they can represent a kind of universal computing machines. And some even wonder whether the whole Universe is a cellular automaton. You can find out more in these Plus articles: