Maths in a Minute: The Harmonic Series

Maths in a Minute: The Harmonic Series

There are some series (infinite sums of numbers) in mathematics that are so common, that arise so often, that they get given their own name. Some you might recall from your school days. For example, one such series might be,

$1+3+5+7+9+11...$

This is an example of an arithmetic series - when there is a constant difference between subsequent terms in the series. In this case, we add the number 2 to each term to get to the next term in the series. You’ll notice that by adding up sufficiently many terms of the series, you can get the result to be larger than any positive number.

For example, if you choose the number 100, a quick bit of mental maths (or phone calculator maths) will tell you that the sum of the first 11 terms is 121, so within a finite number of terms, we can exceed the number 100. Since we can exceed any number within a finite number of terms, we say that the series diverges to infinity.

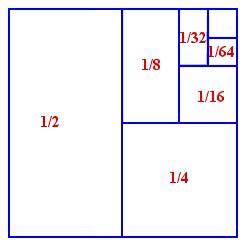

Not all series do diverge, however. For example, consider a geometric series, where each term in the series is a constant multiple of the one before it. One such series might be

$\frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{4} + \frac{1}{8} + \frac{1}{16} ...$

Where, from sequence term to sequence term, we multiply by $\frac{1}{2}$. In this case, instead of diverging like the arithmetic series, the series converges to 1. Quite a nice geometric proof is to consider these numbers as areas of rectangles within a square of side length 1. Because the area of the square is 1, and the rectangles fill out the square, we see their combined area converges to 1.

Let’s now look at a similar-looking series, called the harmonic series,

$1 + \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{3} + \frac{1}{4} + \frac{1}{5} + \frac{1}{6} + …$

Does this converge? And if so to what value? It seems similar enough to the geometric series that maybe it should converge. However, it turns out that this is not the case.

There’s a nice proof of this first discovered by Nicole Oresme in (c. 1360). The proof involves grouping terms as follows:

$1 + \frac{1}{2}+ \frac{1}{3}+ \frac{1}{4}+ \frac{1}{5}+ \frac{1}{6}+ \frac{1}{7}+ \frac{1}{8}+ \frac{1}{9}+ \frac{1}{10}+ \frac{1}{11}+ \frac{1}{12}+ \frac{1}{13}+ \frac{1}{14}+ \frac{1}{15}+ \frac{1}{16}$

$ = 1 + \frac{1}{2}+ (\frac{1}{3}+ \frac{1}{4})+ (\frac{1}{5}+ \frac{1}{6}+ \frac{1}{7}+ \frac{1}{8})+ (\frac{1}{9}+ \frac{1}{10}+ \frac{1}{11}+ \frac{1}{12}+ \frac{1}{13}+ \frac{1}{14}+ \frac{1}{15}+ \frac{1}{16})$

And then we can find another series with terms grouped in brackets so that each bracket is smaller than the corresponding one in the harmonic series.

$ 1 + \frac{1}{2}+ (\frac{1}{4}+ \frac{1}{4})+ (\frac{1}{8}+ \frac{1}{8}+ \frac{1}{8}+ \frac{1}{8})+ (\frac{1}{16}+ \frac{1}{16}+ \frac{1}{16}+ \frac{1}{16}+ \frac{1}{16}+ \frac{1}{16}+ \frac{1}{16}+ \frac{1}{16})$

But now we can notice that the bracketed terms all add up to ½

$= 1 + \frac{1}{2} + (\frac{1}{2}) + (\frac{1}{2}) + (\frac{1}{2}) + … $

And now this smaller series diverges to infinity. Hence, the harmonic series must also diverge to infinity.

However, before you’ve seen this proof, it is entirely reasonable to have thought that this series didn’t diverge because of just how slowly the sum grows. (Indeed before Oresme, for hundreds of years, mathematicians thought that it would converge for this reason). Indeed, suppose that like with our arithmetic series, we wanted to exceed 100. As you will see from the table below, it takes a huge number of terms to do that. You have to add over 12,000 terms to just exceed 10!

| Number | No. Terms in Harmonic Series to Exceed it |

| $3$ | $11$ |

| $5$ | $83$ |

| $10$ | $12367$ |

| $20$ | $272400600$ |

| $100$ | $1.5 \times 10^{43}$ |

However, the harmonic series will eventually exceed every number. Neat!

About the Author:

Ben Watkins finished his 4th year of mathematics at Cambridge in 2025. His interests include theoretical physics, quantum computation, and mathematical communication: sharing the joy of maths with a wider audience!

Comments

jonesville

I liked this.

Should the “<“ be a “>” after the grouped and bracketed third plus one fourth terms etc? Being greater than a fourth plus a fourth etc

Or have I misunderstood divergence probably

mystified

Andy

Marianne

Thanks for spotting this! The < sign should not have bee there at all. We fixed the typo.