Plus Advent Calendar Door #10: Hawking radiation

Today's door of the advent calendar reveals a surprise: black holes aren't actually completely black.

Ever since the observation of gravitational waves in 2016 we know for sure that there are black holes within our Universe. But these strange and scary objects were not new to physicists, who'd already spent quite some time thinking about them from a theoretical view point.

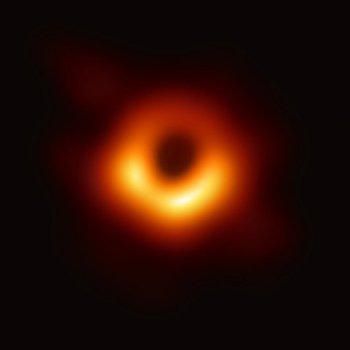

This is the first image of a black hole that was ever taken, released in 2019 (see here to find out exactly what is shown in the image). We have known that black holes exist since 2016 when gravitational waved caused by them were first detected. Image: European Southern Observatory., CC BY 4.0.

The person to make the greatest contribution to the theory of black holes was Stephen Hawking. Using just mathematics, rather than observations, Hawking and colleagues showed that black holes are surprisingly simple objects: they can be described by just their mass, their spin, and their electric charge. It doesn't matter what you throw into a black hole, or how it was created — it could have been made by a dying star, or the collision of two black holes, and it could have swallowed people or the contents of the world's libraries — from the outside all you can see is the black hole's mass, spin, and charge. In the words of the physicists John Wheeler, "Black holes have no hair".

With the no hair theorem, as it became known, Hawking and his colleagues tamed the theory of black holes. But a little later, 1974, Hawking proved another result about black holes, which opened up a a whole new can of worms: he showed that black holes aren't all black after all. Instead — just like a hot cup of tea left sitting to cool down — they emit thermal radiation into their environment.

Like Hawking's previous results on black holes, his theory of what has come to be called Hawking radiation isn't a result of observational evidence, but of mathematics. While pondering a particular puzzle that was intriguing physicists at the time, Hawking considered a hypothetical Universe consisting of a single black hole. Einstein's general theory of relativity makes it possible to study such imaginary worlds, but Hawking also brought in the theory of physics that describes the world at very small scales: quantum mechanics. When applying quantum mechanics to matter outside the black hole, Hawking discovered that some thermal radiation should be emitted by the black hole, and that this should be true for black holes in general.

Admittedly, the temperature of that radiation, now called the Hawking temperature, is nowhere near as that of a hot cup of tea: instead it's incredibly low, only a tiny fraction above absolute zero. We would be hard pressed to ever observe it. But the fact that there should be any radiation at all stunned the physics community.Hawking's result immediately posed a paradox that still hasn't been resolved — in fact, Hawking was still working on it in the last months of his life. It's called the information paradox. Find out more behind tomorrow's door of the 2020 Plus Advent Calendar.

This year's advent calendar was inspired by our work on the documentary series, Universe Unravelled, which explores the work done by researchers at the Stephen Hawking Centre for Theoretical Cosmology and is available on discovery+. Return to the 2020 Plus Advent Calendar.