Secret symmetry and the Higgs boson (Part II)

In the first part of this article we explored Landau's theory of phase transitions in materials such as magnets. We now go on to see how this theory formed the basis of the Higgs mechanism, which postulates the existence of the mysterious Higgs boson and explains how the particles that make up our Universe came to have mass.

The electroweak theory

Dedication of a mural painted by Josef Kristofoletti directly above the cavern of the ATLAS Experiment at CERN, which searches for the Higgs boson. (Copyright CERN Geneva.)

Over the last 400 years physicists have steadily revealed the connections between the many and varied forces that control the motion of the bodies around us and give structure to the matter from which our Universe is formed. By the middle of the 20th century all known phenomena could be accounted for in terms of just four forces: gravity and electromagnetism, plus two forces that play important roles in nuclear physics — the weak force and the strong force.

The strong force holds subatomic particles together to form protons and neutrons and binds these protons and neutrons together to form the nuclei of atoms. The weak force is also extremely important, as it is able to transform protons into neutrons and neutrons into protons and thereby transmute the elements. The weak force is vital for the synthesis of all the atoms heavier than hydrogen within very massive stars. These atoms are dispersed into space in the supernovae explosions that end the lives of these supergiant stars. They may then be incorporated into the material that forms later generations of star systems such as our own.

Electromagnetism and the weak force have completely different characteristics. The electromagnetic force holds atoms together with negatively charged electrons bound to a positively charged nucleus. But electromagnetism also operates over very long distances. For instance, the Earth's magnetic field will attract the tip of a compass needle wherever the compass is located on Earth. By contrast, the weak force is an extremely feeble force that only operates over a very short distance — approximately one thousandth of the diameter of a proton.

In the 1950s attempts were made to construct models that united the electromagnetic and weak forces within a single theory. These elegant models were built around symmetries between fundamental particles. (When physicists talk about symmetry they mean a transformation of an object that leaves the object unchanged. For instance, if a snowflake is rotated by 60 degrees around its centre, its appearance remains the same.) Symmetry was a critical component of the electroweak models and this implied that they were rigid structures that could not be adjusted arbitrarily to fit the facts. For the models to work, the symmetry had to be exact.

But there was a problem. Particle physics tells us that the fundamental forces operate by the exchange of force carrier particles known as gauge bosons. For instance, the electromagnetic force acts by the exchange of massless units of light called photons. The weak force could be described in the same way, and its weakness would be explained if it were mediated by gauge bosons that, in stark contrast to photons, do have mass. Unfortunately, the inclusion of these massive particles seemed to completely destroy the symmetry embedded in these theories, thereby rendering them inconsistent and useless.

The physicist Peter Higgs recognised that what was required was a symmetry breaking mechanism that hid some of the symmetry of the original theories, whilst retaining all the nice features that symmetry brought to these theories. Higgs realised that Landau's model (explored in the previous article) would fit the bill nicely.

In 1964 Higgs translated Landau's ideas into the language of particle physics and constructed a model that demonstrated how, in principle, the symmetry encapsulated in theories of forces such as electromagnetism or the weak force could be spontaneously broken.

This would be the basis for a unified theory of the electromagnetic and weak forces. They could now be considered as two manifestations of a single electroweak force, thus reducing the number of independent forces from four to three. This represented the greatest unification of the forces since the unification of the electric and magnetic forces by Michael Faraday and James Clerk Maxwell in the 19th century. Higgs did not attempt to construct such a theory himself, but he came up with the theoretical mechanism behind it. Steven Weinberg took the next step and applied Higgs' idea to an electroweak model that had earlier been studied by Sheldon Glashow. Abdus Salam worked independently on a similar model and the theory is known as the Glashow-Weinberg-Salam (GWS) model.

Ripples in a quantum jelly

Peter Higgs. Notice the Mexican hat diagram on the left of the blackboard. (Copyright Peter Tuffy, The University of Edinburgh)

So how does the model constructed by Peter Higgs work? We sometimes think of fundamental particles as though they were tiny billiard balls moving around and bouncing off each other. But in the quantum field theories that describe the world at subatomic distances, this picture does not apply. Such theories associate each species of fundamental particle with a quantum field which permeates the whole of space. At each point in space the field fluctuates like a spring or simple harmonic oscillator. What we interpret as particles are excitations in the field.

You can think of this field as a sort of quantum jelly that extends through space. Where there is no particle the jelly just wobbles in a regular fashion. A particle corresponds to a ripple in the jelly, a disturbance of the regular wobble, at a particular point. So a particle travelling along corresponds to a ripple travelling through the jelly, and two particles interacting correspond to two ripples meeting.

Mathematically such a quantum field is represented by something called a scalar field: a number associated to every point in space. The number captures the effect the field would have on a particle interacting with it at that point.

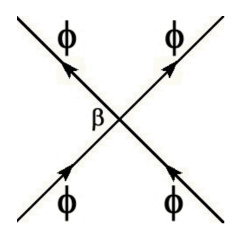

Higgs constructed a model in which a quantum field $\Phi$ plays the role of the order parameter in Landau's theory. He realised that if the potential energy of his new field was defined to have exactly the same form as in Landau's theory, then it would provide a symmetry breaking mechanism that could be applied to the fundamental forces in particle physics. Higgs wrote down the following expression for this potential energy at a given point: $$V = \alpha \Phi^2+\beta \Phi^4.$$ Here $\Phi$ syands for the value of the field at the point. (You might notice that this is what is written on the blackboard behind Peter Higgs in the photograph above. The only difference is that $\Phi$ is expressed as a complex number so $\Phi^2$ is written as $\Phi*\Phi$.) The excitations of Higgs' hypothetical field correspond to particles. In quantum field theory $\beta$ is interpreted as the strength with which two $\Phi$ particles interact with each other. The four powers of $\Phi$ represent the two $\Phi$ particles prior to the interaction and the two $\Phi$ particles after the interaction. Diagrammatically these interactions are represented as follows:

The direction of time is upwards in the diagram. At the bottom of the diagram two particles approach each other, at the centre they interact with strength β, then at the top they recede from each other again.

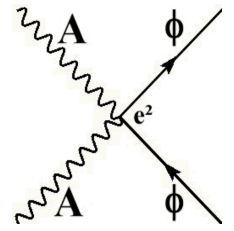

Time runs upwards in this diagram. It represents a process in which an A particle and a Φ particle approach each other, interact with strength e2 and then recede from each other again.

A massive phase transition

Higgs proposed that immediately after the Big Bang the Universe went through a dramatic phase transition. At extremely high temperatures in the very early Universe, the parameter $\alpha$ was positive. The lowest energy configuration would then be one in which the $\Phi$ field is zero everywhere. In our model of a magnet (see the previous article) this corresponds to a state above the critical temperature where the magnetisation is zero.

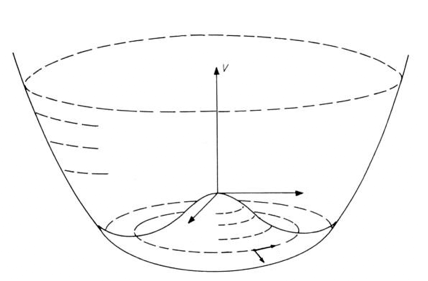

But, in accordance with Landau's theory, as the temperature dropped the value of $\alpha$ decreased until below a critical temperature of perhaps a trillion degrees it became negative. The energy graph would then look like the Mexican hat diagram.

Mexican hat diagram

Below the critical temperature the lowest energy configurations of the $\Phi$ field correspond to a circle within the brim of the hat. The $\Phi$ field now loses energy and the system falls randomly to one of the points on the minimum energy circle. At each point $\Phi$ now fluctuates around a non-zero value that minimises the energy. We will give this value of $\Phi$ the label $t$. Τhe result is that the $\Phi$ field is no longer zero even in completely empty space, just as the magnetic field in a permanent magnet is not zero.

Acquiring mass

The quantum field $\Phi$ oscillates around $t$, the minimum energy value of the field. Effectively, the Higgs field has two parts: one part is this constant background field and the other part is variable and it is the excitations of the variable part that correspond to the Higgs particles. All the particles that interact with the Higgs particles will also interact with the background field. To make this explicit, we can rewrite as follows: $$\Phi=t+H.$$ Expanding the expression for the potential energy in the $\Phi$ field in terms of $H$ will explicitly show the effect of the symmetry breaking. We won't write the whole expression down here, but just note that the result is a constant term, which particle physicists usually disregard as it simply shifts the energy scale, then there are a quadratic term and a quartic term just as there were for the original $\Phi$ field, but now there is also a term proportional to $H^3$, so the energy is not symmetrical under the transformation that send $H$ to $-H$. The symmetry of the system has been lost or spontaneously broken in the new low energy configuration. But more important is the effect that this symmetry breaking has on the photon-like $A$ particle. The interaction between the $\Phi$ particle and the $A$ particle is represented by the term $e^2A^2\Phi^2.$ Rewriting this in terms of the Higgs field gives $$e^2A^2(t + H)^2,$$ which expands to $$e^2t^2A^2+2e^2tHA^2+e^2H^2A^2.$$ The second and third terms contain contributions from the $A$ field and the $H$ field: they represent interactions between the Higgs particle and the $A$ particle. But the first term is the one that we are most interested in. It represents the interaction between the $A$ particle and the background field whose value we have labelled $t$. It is a quadratic term in $A$ multiplied by a constant $e^2t^2$. As noted above, in quantum field theory this represents a mass term for the $A$ particle. In the symmetric phase at temperatures above the phase transition the $\Phi$ field oscillates around zero, so in this case $t=0$ and the force carrying particle $A$ has no mass. But at tempratures below the critical temperature at which the phase transition occurs $A$ has a mass equal to $e^2t^2$. This is the magic of the Higgs mechanism. The symmetry of the force has been spontaneously broken and the photon-like particle that mediates the force has been transformed into a massive particle.The state we are in today

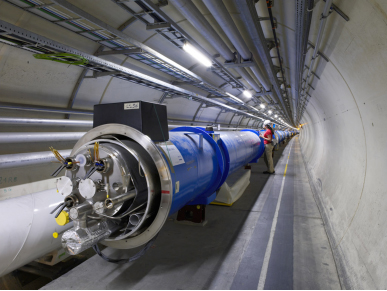

The tunnel of the Large Hadron Collider during construction. The sealed ends of the two beam pipes can be seen side-by-side projecting from the end of the pipeline. ( Copyright CERN Geneva.)

But is the theory true? Does it represent the way that the Universe really works? Many of the predictions of the electroweak theory have now been verified in particle accelerators. The most spectacular was the discovery of the massive W-plus, W-minus and Z-nought particles at CERN in 1983. The only prediction that remains to be confirmed is the existence of the Higgs particle itself. Recent hints from the Large Hadron Collider suggest that an announcement of its discovery is just a matter of time. (see Hooray for Higgs).

About the author

Nicholas Mee studied particle physics and mathematics at the University of Cambridge. He was Senior Wrangler and went on to complete a PhD there with the title Supersymmetric Quantum Mechanics and Geometry. He is the founder of the educational software company Virtual Image.

Mee is the author of the book Higgs force: The symmetry-breaking force that makes the world an interesting place, which has been reviewed in Plus.

Comments

Anonymous

You write:

The only difference is that is expressed as a complex number so φ^2 is written as φ* φ.

This looks like the "*" is an ordinary multiplication. But it means the complex conjugation a+bi->a-bi.

So the star has to be a superscript instead.

Mark81

This is the first explanation I've seen of the Higgs field that is accessible enough to read without prior knowledge of gauge theories and all the rest, while still having enough detail to explain some of how it works. Good read!