Smale's chaotic horseshoe

On November 30th 1889 the French mathematician Henri Poincaré had a problem. He had been awarded a mathematical prize, offered by no lesser person than King Oscar II of Sweden, for his work on a question that was bothering mathematicians. Using Newton's laws of motion and gravitation you can in theory work out how a number of objects (say stars, planets and moons) should move due to the gravitational pull they exert on each other. If there are only two bodies involved the answer is straight-forward: they move along curves that are easy to describe (ellipses in the case of a planet orbiting a star). The problem was, what happens if you throw a third object into the mix?

Stephen Smale talks about the horseshoe at a (somewhat noisy) press conference at the Heidelberg Laureate forum 2017. Click here to see a video of Smale talking about other aspects of his work, and his career in general.

Things get tricky in this case, but Poincaré did some outstanding work trying to characterise motions that could result in a system with three bodies. The problem he had in November 1889 was that the work contained a mistake. Poincaré did the right thing. He owned up and even paid for the copies of his work that had already been printed. He revised his competition entry, still got the prize, and later wrote more extensively about what the mistake had revealed to him. What it had revealed was the existence of chaos.

Fast forward to 1960 and the beaches of Rio, where the mathematician Stephen Smale was thinking about a problem inspired by the maths of radio waves. The complexity of the problem worried him, especially since he had previously conjectured that there was no such thing as chaos. "I made some pretty bad predictions," he says. "[Norman] Levinson at MIT pointed out that there were these old papers by a pair of English mathematicians [Mary Cartwright and J. L. Littlewood]. They had interesting results which contradicted what I had predicted, and I wanted to understand what they did. So I put what I did in a very geometric context so I could understand it."

The result is now know as Smale's horseshoe map. It beautifully encapsulates how chaotic dynamics can arise in mathematics and goes straight to the heart of the problems Poincaré had encountered when thinking about his three-body problem. "Poincaré got a big mess, and [the horseshoe] put order in the mess."

The horseshoe

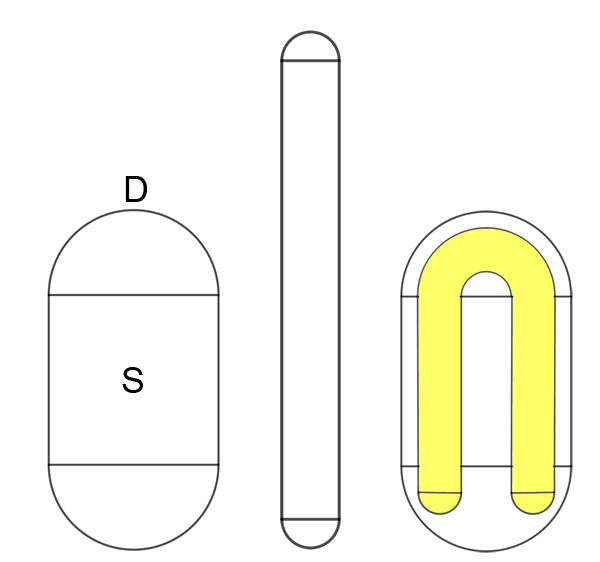

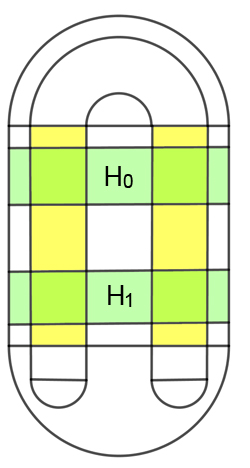

Look at the region $D$ shown below, made up of a square $S$ with two rounded-off ends stuck on at the top and at the bottom. Imagine picking this region up, squeezing it in the horizontal direction and stretching it into the vertical direction so that it becomes long and thin, and then bending it round to the right to form a horseshoe. Now place it back down into the original region $D$ as shown. (We could describe this operation using mathematical formulae, but the beautiful thing is that we don't need to — as you'll see, the essence of the dynamics can be captured conceptually.)

The horseshoe map.

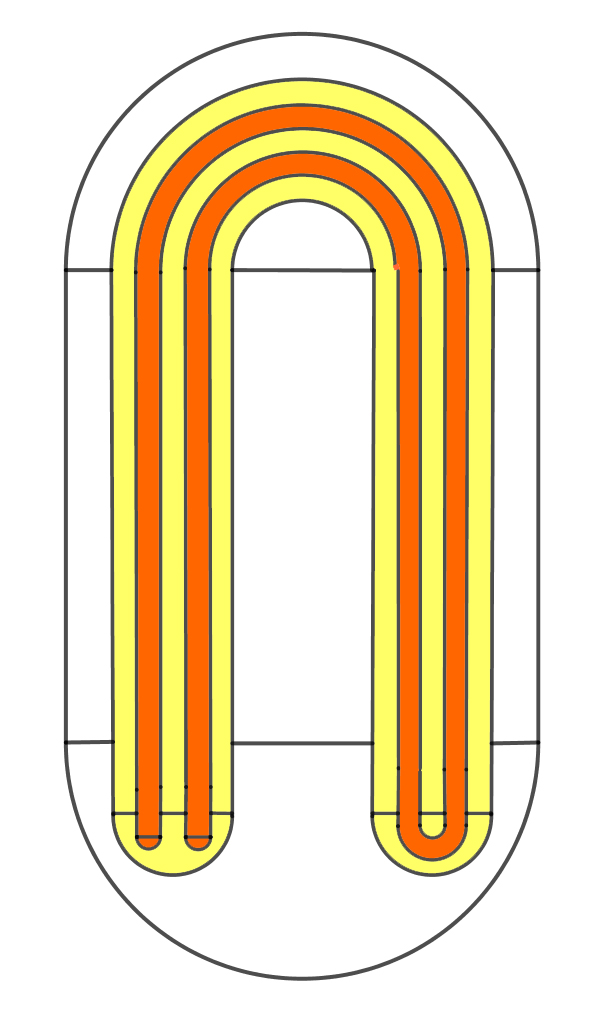

Applying the horseshoe map twice to the region D gives a folded horseshoe.

Horseshoe dynamics

The operation gives a dynamical system: as you apply the operation repeatedly, points in the region $D$ are moved around $D$. A point $x_0$ in $D$ is moved by the operation (which we'll call $f$) to another point $x_1$ in the horseshoe, which in turn is moved to a point $x_2$ in the folded horseshoe when you apply $f$ again, and so on. You can continue like this indefinitely to get an infinite sequence $x_0, x_1, x_2, x_3,...$ of points. That sequence is called the forward orbit of $x_0$.

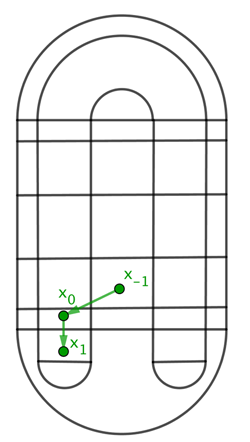

The point x-1

maps to the point x0 under f, which in turn maps to x1.

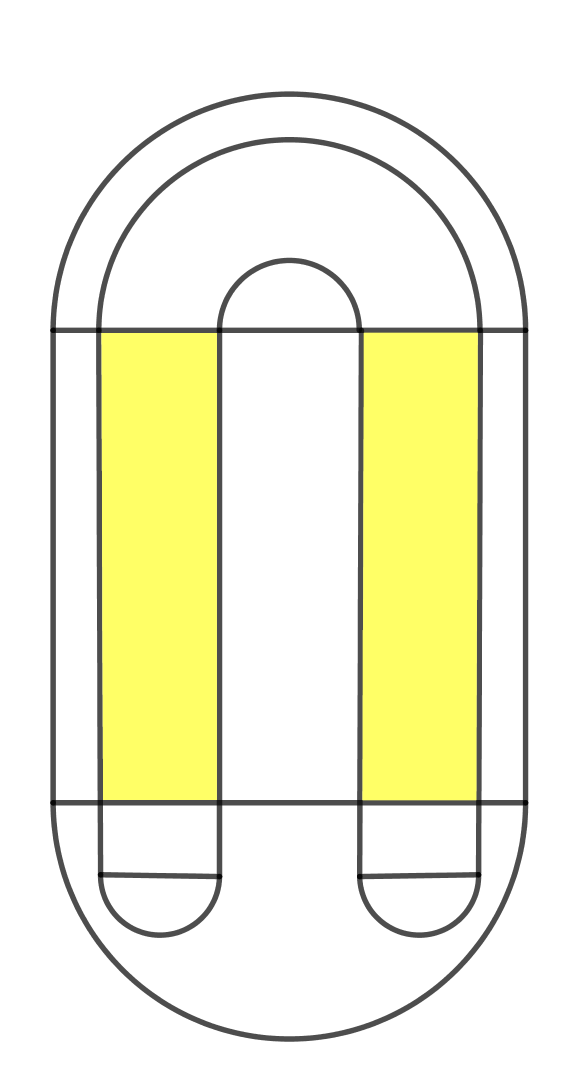

If x0 is in S and x1 is also in S, then x1 lies in one of these two vertical strips.

If x0 is in S and x1 is also in S, then x0 lies in one of the two horizontal strips.

Shifty dynamics

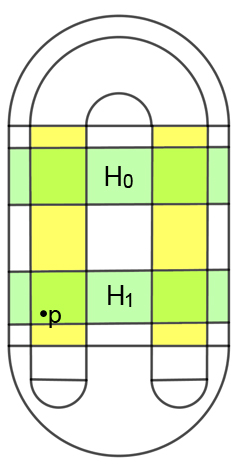

This means we can write down a sequence for each $x_0$ in $L$. First, write down a $0$ if $x_0$ in $H_0$ and a $1$ if $x_0$ in $H_1$. Now look at $x_1$ and write down a $0$ if $x_1$ in $H_0$ and a $1$ if it's in $H_1$. Then look at $x_2$ and write down a $0$ if $x_2$ in $H_0$ and a $1$ if it's in $H_1$. And so on. For each point $x_n$ in the forward orbit of $x_0$ you write down a $0$ or a $1$. This gives you an infinite sequence of $0$s and $1$s. We can write down a sequence for the backward orbit of $x_0$ in a similar way, only now we write it from right to left. The first entry (on the right) is $0$ if $x_{-1}$ is in $H_0$ and $1$ if $x_{-1}$ is in $H_1$. The second entry (from the right) is $0$ if $x_{-2}$ is in $H_0$ and $1$ if $x_{-2}$ is in $H_1$. And so on. This gives a sequence of $0$s and $1$s, infinite in the left. Now glue the two sequences together, with a dot between the sequence to separate them. For example the sequence $$...11111111.111111111...$$ denotes the point $p$ whose entire backward and forward orbits lie in $H_1$.

The point p whose sequence consists entirely of 1s.

It turns out that the correspondence between these bi-infinite sequences and points in $S$ whose orbits never leave the square is exact. You can prove that for every point in $L$ there is a unique bi-infinite sequence with a dot, and for every bi-infinite sequence with a dot there is a unique point in $L$. If two points in $S$ are close to each other, then their corresponding sequences agree to a large number of places to the left and right of the dot, and vice versa — the closer they are, the more places agree. And best of all, applying the map $f$ to a point in $S$ corresponds to shifting the dot in its sequence to the right by one place, and applying $f$ backwards corresponds to shifting it along to the right by one place. This kind of symbolic dynamics is used a lot in the theory of dynamical systems and it often makes things marvellously transparent, as we will see next.

About this article

Marianne Freiberger is editor of Plus. She talked to Stephen Smale at the Heidelberg Laureate forum 2017.

Comments

Max

Hey now - is someone trying to make a Damascus horseshoe here...?