Solving quadratics in pictures

A Babylonian inscription from around 2800 BC.

Algebra is old: the Babylonians, a people who lived around 3000 years ago, already knew about versions of the famous formula for solving quadratic equations. But what they were inspired by was geometry: they needed to solve quadratics in order to work out problems involving areas of plots of land. So to celebrate their achievement, let's derive the famous quadratic formula using geometry.

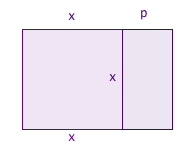

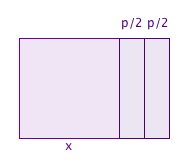

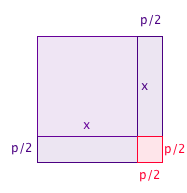

Suppose the quadratic equation you are looking at is $$x^2 + px = q,$$ with $p$ and $q$ both positive numbers. The term $x^2$ gives the area of a square with sides of length $x.$ The term $px$ gives the area of a rectangle with one side of length $p$ and the other side of length $x$. We can put the square and the rectangle next to each other to get a larger rectangle:

To say that the Babylonians knew this formula is a little misleading. Firstly, they didn't know about negative numbers, so they could only solve quadratics that had a positive solution. Also, they didn't write their maths using symbols and letters as we do, but using words. So a Babylonian student might be given questions such as:

If I add to the area of a square twice its side, I get 48. What is the side?

Which, writing $x$ for the side, translates to the equation $$x^2+2x=48.$$ The Babylonians knew about sequences of steps they could perform to find the solution to such a question — which is why we say they knew about the quadratic formula.

Comments

Anonymous

Just a curiosity question, other than torturing Babylonian algebra students, what did they use the Quadratic Formula for?

Anonymous

After the part where the rectangles are rearranged, it says: "still has area p^2 +px=q...".

It should be x^2 instead of p^2.

Marianne

Thanks for pointing that out, we've corrected it!