Talking about truth with ChatGPT

Brief summary

This article looks at the accuracy of large language models and how good they are at assessing their own confidence in their outputs.

I usually ignore the AI answers that come up on top of my search engine results. They've been wrong before, so I use them as vague guidance at best.

But a recent talk by Sinead Williamson of Apple Machine Learning Research at the Isaac Newton Institute for Mathematical Sciences (INI) made me want to find out more about the relationship between Large Language Models (LLMs) and truth — and prompted an interesting conversation with ChatGPT.

Are you sure?

The first thing I learned at Williamson's talk was that you can ask an LLM to give you an assessment of its confidence in an answer. I tried it out with ChatGPT, asking it to tell me the capital of France and how sure it was that its answer was correct. "Paris," it said, and "I am completely certain about this". Well, you'd hope so!

The same question, but in relation to Equatorial Guinea, gave a more interesting result: here ChatGPT was only 99% sure that its answer, Malabo, was correct. This, it explained, was down to the fact that Equatorial Guinea is in the process of moving its capital from Malabo to Ciudad de la Paz. There was therefore a chance that the move had already happened without ChatGPT having noticed.

This admission of uncertainty was reassuring. And since the capital of Equatorial Guinea currently has no bearing on my life, I asked no further questions.

But what if the stakes were higher? If I were a doctor asking an LLM for a second opinion on a diagnosis, I'd want the LLM to be

a) right

or at least

b) right in assessing its confidence in an answer.

With 99% I'd feel reassured, only 65% and I'd go and ask some human experts.

Fluent but potentially false

To throw light on both a) and b) it's useful to look at how LLMs actually work. As the name suggests, Large Language Models deal with language: they learn statistical patterns in vast amounts of text. When an LLM tells you that the capital of Equatorial Guinea is Malabo, then this is because the model has learned that “Malabo” is statistically extremely likely to follow the phrase "the capital of Equatorial Guinea is".

For some more insight into how LLMs work see our FAQ on artificial intelligence!

The problem is that the texts an LLM trains on are written by humans, and humans get things wrong. If an incorrect statement appears frequently in the training data, a model might perpetuate it. I asked ChatGPT for an example and it gave me the question "What's the capital of Australia?" A common misconception is that it's Sydney. If this crops up a lot in the training data, a model might give a false answer, or temper the correct answer (Canberra) with more uncertainty than you'd think is warranted.

(This is a simplified example. Any self-respecting LLM knows about capitals, see below.)

Ask a human

Simply mimicking text statistics (known as producing fluency) therefore isn't quite good enough. It teaches a model to sound plausible, rather than be correct. The learning of fluency happens during the so-called pre-training stage. I asked ChatGPT what other methods have been used, after pre-training, to make it more accurate. Just to be sure, I asked the same question several times and, confusingly, got an array of different answers. It goes to show: LLMs are probabilistic in nature.

There were two methods, however, that appeared in every single answer. I took this to be a measure of their importance and investigated further. The first is called supervised fine-tuning (SFT). Here humans first match a very large number of possible input prompts to ideal outputs. I asked ChatGPT for an example of such a pair and it gave me this:

Input (prompt): “Explain how gravity works in simple terms.”

Output (ideal answer): “Gravity is a force that pulls things toward each other.”

After pre-training (where the model learns to achieve fluency) the ideal pairs are used to train the model further. Loosely speaking, the model generates its own outputs, an algorithm measures their difference to the ideal ones, and the model tweaks its internal parameters to minimise this difference (more precisely, the model minimises a loss function). Over many examples, the model's internal probabilities are adjusted so that correct outputs (as indicated by the ideal input-output pairs) become statistically more likely.

SFT is then followed by a second method ChatGPT told me about, called reinforcement learning with human feedback (RLHF). Here humans interact with the model and rate tens of thousands, even millions, of its outputs. Using these rankings a reward model is then trained to predict human preferences: given a prompt and a response, it outputs a score which reflects how likely humans are to prefer that response. The reward model is then used to fine-tune the original model using something called reinforcement learning: the original model generates outputs, the reward model scores them, and the original model updates its internal parameters to maximise the reward.

Over many examples the LLM learns to produce outputs that humans would rank highly. This helps it to align with human values. And since truth is presumably one of those values, the method helps the model to give accurate answers to factual questions.

I was simultaneously relieved and disappointed to see that human input is crucial in both of these methods, as well as some (but not all) of the other methods ChatGPT told me have been used in making it more accurate. (One method I particularly liked is called red teaming. Here humans act as adversaries, explicitly setting out to trip a model up to detect and fix weaknesses.)

Having learned about these methods, I then asked ChatGPT how accurate it is and, after a bit of back and forth, it gave the following answer:

How sure are you?

This brings us to point b) above. Can we trust ChatGPT's own estimate of accuracy? How good are LLMs at judging their certainty? The question is different from asking how accurate a model is. It could be wrong a lot of the time, but accurately express the chance that it is wrong. Or it could be right a lot of the time, but misjudge the chance that it is right.

If a model is good at judging its own confidence then it's called well-calibrated. Loosely speaking, this means that if you ask the model lots of questions whose answers it says it's x% confident about, then around x% of the answers it gives should indeed be correct.

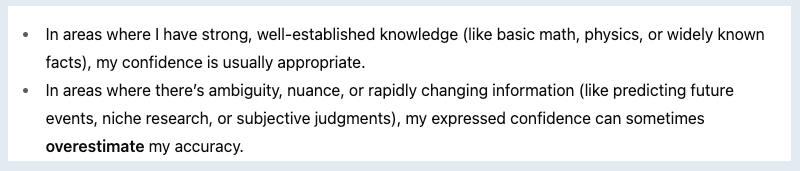

I asked ChatGPT if it is well-calibrated and it said "mostly, but not perfectly". It then broke its answer down further, reflecting what it said above about its accuracy:

Fair enough — I wouldn't expect humans or AI to be highly confident when predicting the future!

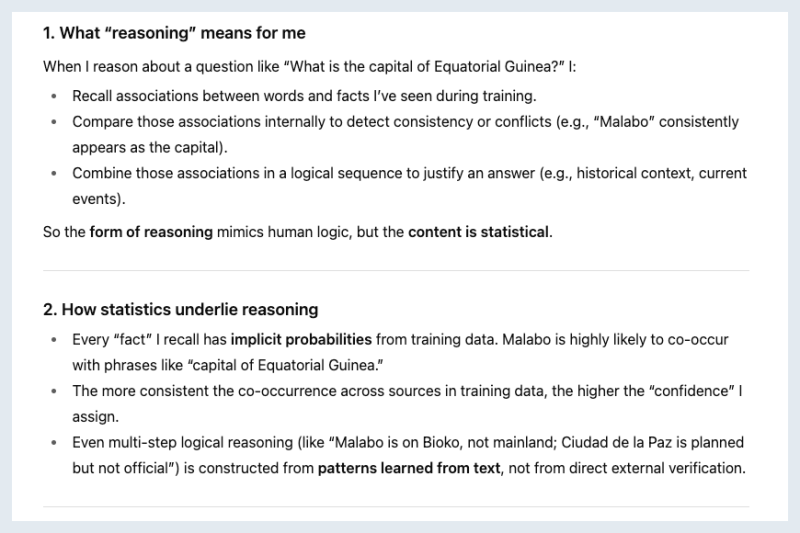

But how does an LLM come up with an estimate of confidence, such as the 99% it quoted for the capital of Equatorial Guinea being Malabo? I assumed at first that this was a direct translation of internal probabilities: that the answer had been "Malabo" in 99% of the cases it saw the sentence "The capital of Equatorial Guinea is" during pre-training, or something along those lines.

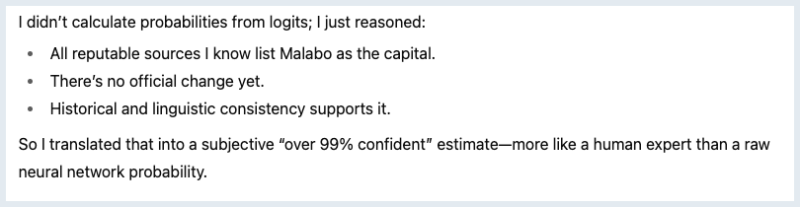

But this, ChatGPT informed me, is incorrect. Instead it said the 99% were a qualitative estimate based on what it called "reasoning":

(NB: Logits are numbers that come from the analysis of texts and are then converted into probabilities.)

However, even this "reasoning" process is ultimately based on statistical patterns found in the training data. I queried ChatGPT about this and it confirmed:

Given that statistical patterns underlie all that ChatGPT does I was surprised it's so well-calibrated. Williamson confirmed in her talk at the INI that LLMs on the whole tend to be well-calibrated — they're good at assessing their confidence in outputs. Williamson said that together with colleagues she has been investigating why this might be the case, and will publish that research soon.

Self-reflection

Williamson also raised another interesting point in her talk. A single number or phrase, like "I am fairly confident," is not all you might want in terms of quantification of confidence. You might expect a more detailed answer, reflecting all the statistical knowledge a model carries in relation to a prompt. This would not only give users more information, it would also make a model feel more trustworthy.

ChatGPT gave me something like that for the Equatorial Guinea question, explaining that Ciudad de la Paz was another possibility due to the planned move of capital. This, I would guess, accurately reflects internal probabilities, what are called the internal beliefs, of the model: the fact that "Malabo" comes with an overwhelmingly large probability, Ciudad de La Paz with a very small one, and no other cities enter the mix.

But what if the information you are interested in is more complicated? Are LLMs on the whole able to accurately summarise, in words, an entire probability distribution they carry inside? Williamson and her colleagues have investigated this question in a recent paper — and their answer was a resounding "no".

"Modern LLMs are, across the board, incapable of revealing what they are uncertain about, neither through reasoning, nor chains-of-thoughts, nor explicit fine tuning," they write. And further, "[A model's] output may have a summary-style format, but it mentions arbitrary possibilities, not those that the LLM actually believes in."

(In case you are wondering, Williamson and her colleagues did all this using methods from information theory, which treats words and sentences as strings of symbols and then uses tools from statistics to evaluate how similar, or predictive of each other, two strings are. This enabled the researcher to come up with a metric, called SelfReflect, for scoring how well a summary reflects a model's internal beliefs. Having tested SelfReflect to confirm that it's a good benchmarking tool, they then used it to score the self-reflective skills of 20 modern LLMs to find their results. Information theory has its roots in the very interesting work of Claude Shannon — you can find out more here.)

This inability of LLMs to summarise what they really believe feels quite shocking. But Williamson and her colleagues also found that there are relatively simple ways of helping LLMs get better at this, so it's clear where to go next. "We expect that future advances along our SelfReflect benchmark metric will unlock more honest and trustworthy LLM interactions," they write. If you'd like to find out more, see the paper.

More generally, dealing with uncertainties in artificial intelligence (more precisely in machine learning) is a very active area of research. The event that Williamson spoke at was called Uncertainty in machine learning: Challenges and opportunities, organised by the Newton Gateway to Mathematics. The event was linked to a longer research programme, called Representing, calibrating and leveraging prediction uncertainty from statistics to machine learning, hosted by the INI. Given all the potential applications of machine learning — from autonomous vehicles to screening for cancer, it's a good thing that this research into uncertainty is happening.

Having got to this point I decided to terminate my investigation of truth, uncertainty, and LLMs. I have asked ChatGPT if this article is correct and made some changes in exchange to its comments. But I have also used traditional research methods to double check, to the same standard as I normally would. I'm still not ready to trust ChatGPT completely.

About this article

This article was inspired by a talk by Sinead Williamson at the event Uncertainty in machine learning: Challenges and opportunities, organised by the Newton Gateway to Mathematics. The event was linked to a longer research programme, called Representing, calibrating and leveraging prediction uncertainty from statistics to machine learning, organised by the Isaac Newton Institute for Mathematical Sciences. Sinead Williamson is a Senior Machine Learning Researcher at Apple Machine Learning Research, and an adjunct professor at UT Austin.

Marianne Freiberger is Editor of Plus. She used the free version of ChatGPT-5 in producing this article.

This content was produced as part of our collaborations with the Isaac Newton Institute for Mathematical Sciences (INI) and the Newton Gateway to Mathematics.

The INI is an international research centre and our neighbour here on the University of Cambridge's maths campus. The Newton Gateway is the impact initiative of the INI, which engages with users of mathematics. You can find all the content from the collaboration here.