'The universal machine'

The universal machine

Written and directed by David Byrne

When we arrived at the The New Diorama Theatre in London we didn't know what to expect. The universal machine is a musical about the life of mathematician and WWII code breaker Alan Turing. Turing was a tragic genius, he is now recognised as the father of computer science, his work during the war saved many lives, but he died young and in unclear circumstances after having been convicted for his homosexuality and chemically castrated. A lot of material for a play — but a musical? I have only seen one musical in my whole life, Cats, and it made me feel ill, so I really could not fathom how this was going to work.

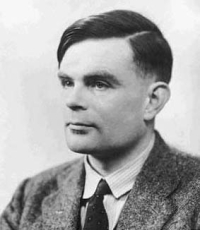

Alan Turing

But as it turned out, we loved it. This isn't a musical with top hats and tear jerkers. Music, written by Dominic Brennan, and choreography weave surprisingly naturally into the story, bringing across aspects that are too emotionally, and even scientifically, complex to spell out in ordinary dialogue. And Byrne deals sensitively with points that could easily be trivialised through over-dramatisation: Turing's arrest, the chemical castration and the suspected suicide.

The New Diorama is a tiny theatre, seating 80 people, whose stage could just about accommodate the cast. Lead actor Richard Delaney's physical resemblance to the Turing we know from photographs was astounding, but when the show first started my heart sank. The opening scenes and first song depict Turing's relationship with his mother and move to boarding school, focussing heavily on his social awkwardness. This, I worried, is just another clichéd portrayal of a mathematician as a nutter, the deranged genius, which has been sucked dry in I don't know how many films and plays. But mid-way through the first half of the show my scorn evaporated. Performances, notably Delaney's and that of Judith Paris, playing Turing's mother and perhaps the most impressive singer, were excellent and I was reminded that Turing's introversion was after all a defining streak of his personality. Having a young Turing exclaim, repeatedly, that he wanted to be a machine may seem like a cheap ploy but it's authentic. The depiction at the end of the first half of Turing's work as part of a team of code breakers, made visceral by music and movement, nearly had me in tears.

The show naturally focusses on the emotional aspects of Turing's story. We all know what the high-points are and Byrne refuses to spell those out yet again. Instead, he focuses on the flesh that surrounds the well-known skeletal story. For example, the emptiness that followed the heroic effort to crack Enigma and the code breakers' anti-climactic anonymity came across particularly well (though I personally could have done with less of Turing's land lady who seemed to embody some of that). The question of whether Turing's death was a suicide is skillfully left open and his relationship with his colleague and short-term fiancée, Joan Clarke, portrayed with gentleness. Even if maths and computers leave you cold, there is a lot to take away from this show.

But for us the representation of Turing's work was a main point of interest. Being musically challenged we did not pick up on the mathematical patterns that apparently permeate the music (see our interview with director David Byrne), but the music did fantastically conjure up the fevered activity and creative excitement of the code breaking team as they worked to crack the German codes. And equally it conveyed the despair the team felt as all their hard work was methodically destroyed at the end of the war in the name of national security.

The universal machine poster detail.

The mathematics itself features in other ways too. The Enigma machine is explained in sufficient detail for everyone to get the drift and the representation of the building of the bombe, the machine designed to crack Enigma, is fantastic: the workings of many minds stretched to the limit against the ticking clock brings across the power of brains over bombs and the power of mathematical thought.

Turing's work on morphogenesis, the formation of patterns in living organisms, makes a prominent appearance as a metaphor for broken equilibrium during the time of Turing's chemical castration. Slightly wonky, perhaps, but the show gets away with it. Delaney speaks Turing's own poetic words and the juxtaposition of science, poetry and emotion is moving. The famous Entscheidungsproblem also makes a fleeting appearance, representing Turing's work on logic and the sceptical reception it received from many of his peers. The unsolvability of the Entscheidungsproblem, which Turing proved, hints at limits to the kind of mechanised thought he was dreaming of. I'm not sure if this was picked up on, but what did come through clearly via words, music and movement and throughout the show was Turing's driving motivation: to build a thinking machine.

All in all Byrne's production is quite heroic. Not many people would dare to tackle tragedy, maths, and the life of a real person by means of a musical. But the show achieves just the right balance of authenticity and drama, portraying a complex human being whose brilliant contributions benefitted not just mathematics, but the whole of the society that failed him so spectacularly.