Watching water

Almost certainly you have used a brush to paint at least once, if not many times in your life.

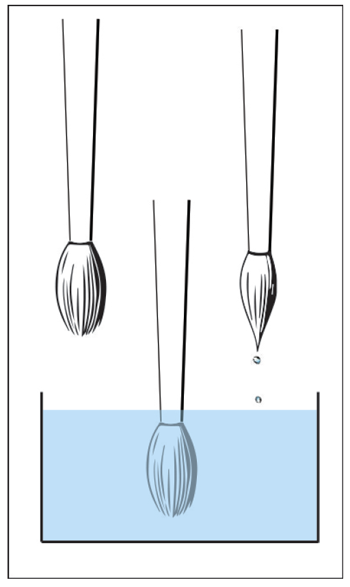

You held the brush in hand, and in order to make the hairs cling together and come to a point, you wet it. Without a doubt, if I take a dry brush, dip it in water, and take it out, the hairs will cling together because they are wet, as we are in the habit of saying. But if I simply hold the brush in the water, it is evident that the hairs do not cling at all:

So it is not exactly the wetness of the brush that makes the hairs cling together. Rather, it is a phenomenon called surface tension.

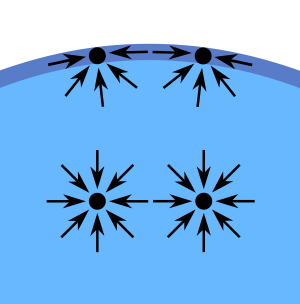

What is surface tension? All of us had the experience of filling a glass of water which crests above the rim of the glass, but doesn't spill over. How can this happen? Think of a liquid as a collection of molecules which exert attraction forces on each other.

FreeImages.com/Diego Baseggio.

Deep inside the liquid a molecule feels equal forces from all directions, but near the surface of the liquid a molecule feels more of a force from inside the liquid than it does from the small number of molecules between it and the surface. Hence, those molecules near the surface are drawn into the liquid and the surface of the liquid displays a "curvature". This property of pulling the surface of a liquid taut is surface tension.

An attractive force between the water molecules creates surface tension.

It is this property which allows some small animals, like the lizard in the movie below, to move on the surface of water.

As for the brush, we see that when it is immersed in water, the forces balance out, but when it is removed from the water, there is a net force of attraction at the wet part of the brush, resulting in the hairs clinging together.

The isoperimetric theorem

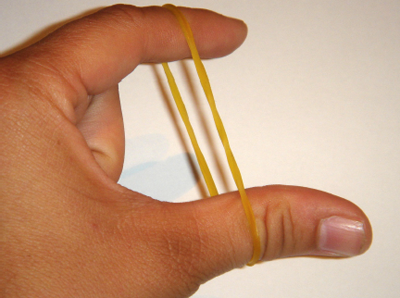

We can also think of surface tension in terms of energy. Energy is a concept that we all understand intuitively. For instance, a taut rubber band or a wave about to crash are all instances where large amounts of energy are stored, waiting to be released.

FreeImages.com/Gisela Royo.

Large amounts of energy are stored in a wave, and then released as it crashes into the rocks.

A molecule in contact with a neighbour is in a lower state of energy than if it were not in contact with a neighbour‚ that is, "it wants" to be in contact with its neighbour. The interior molecules have as many neighbours as they can possibly have, but the boundary molecules are missing neighbours. For the liquid to minimise its energy, the number of molecules on the boundary should be minimised. The result is a minimal surface area. Thus, in order to minimise surface tension, liquids tend to minimise their surface area.

This immediately leads to mathematics. It is a theorem, called the isoperimetric theorem, that in three dimensions the region having the smallest surface area while enclosing a given volume is a sphere. Together with our knowledge of surface tension, this explains why water droplets assume a spherical shape.

Specifically, the energy due to surface tension is proportional to the surface area, and by the theorem, surface area is minimised for the sphere.

The situation is actually a little more complicated because gravity also has an effect. Thus, it is the size of the body of water which ultimately determines its shape; if it is large, gravity dominates and the water flattens; if it is small, surface tension dominates and the water takes on a spherical shape.

We can also explain the odd behavior of the metal mercury. Mercury has a much higher surface tension than water, so even large amounts of it form a roughly spherical shape:

Mercury.

Water.

The isoperimetric theorem mentioned earlier, which says that the sphere minimises surface area subject to a given volume, offers insight into many other phenomena in nature. For example, it tells us why a cat curls up on a cold winter night — to minimise its exposed surface area.

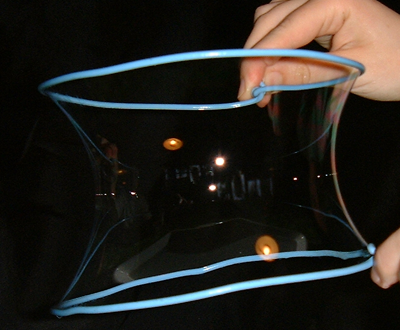

Finally, the effects of surface tension are quite pronounced and visible in soap film. As discussed earlier, surface tension leads a soap film to minimise surface area. Such shapes, called minimal surfaces, are well-studied mathematical objects with many nice properties. Examples include the helicoid and catenoid:

The helicoid. Photo © The Exploratorium.

The catenoid.

About the author

Emmanuel Tsukerman is a PhD candidate in applied mathematics at UC Berkeley. Before starting his PhD, he completed his BS in mathematics and MSc in Computational and Mathematical Engineering at Stanford University.

Comments

Anonymous

"The camphor beetle skates on the water's surface, spreading its legs out wide and using the water's surface tension to prevent it submerging. Lots of beetles do this, but the camphor beetle has evolved a unique technique to avoid predators. When alarmed, it releases a chemical from its back legs that reduces the water surface tension. In this way, the water surface tension on the front pulls it forwards. It shoots forwards on its front feet, which are held out like skis, and steers itself by flexing its abdomen. This tiny beetle is the size of a rice grain but can travel nearly 1m a second in this way. It doesn't hunt on water, but at the water's edge, and saves this trick to escape predators." Guardian.

How does this work exactly? Why should reducing the water surface tension behind it propel it forwards? Is the pull of the water on the beetle the same as the net force of attraction that pulls the hairs of the brush together when out of the water?

Chris G

Anonymous

Following the story about the camphor beetle, can anybody suggest how using a mechanical system (and not the chemical one described above) might be arranged to generate power or extract energy from the surface tension of a liquid? I have tried but its not easy to do this, but it clearly is possible when we consider the cut branch of a tree dripping sap.

MJW Gage

Small boat with camphor at stern and turbine below.