Why not block time?

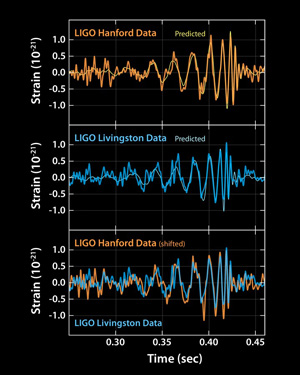

The gravitational wave signals, caused by two colliding black holes, observed by the two LIGO detectors (in Hanford and Livingston) in September 2015. Image: SXS.

When Einstein developed his general theory of relativity in 1915 he revolutionised our view of the Universe. His key insight was unifying space and time into spacetime: space and time were not separate entities but instead different dimensions in the fabric of the Universe. (You can read more about general relativity in this Plus article.)

Einstein's theory has been wildly successful. General relativity enabled Einstein and other physicists to make dramatic predictions about the nature of the Universe. Some of these predictions, such as the existence of black holes and gravitational waves, have only just been confirmed by observations this year. These predictions may have taken a century to observe, but almost all physicists had no doubts that these objects would eventually be seen; we just needed experiments that were sufficiently powerful. But there is one grand implication of Einstein's theory that is yet to be confirmed, and some physicists doubt if it ever will.

Time to give up

When Einstein unified space and time, he removed time's special status. So just as we think of the universe as containing all of the three-dimensional space, it is a natural consequence of general relativity to think of the universe as also containing all of the time. This new view of the universe is called block time – where all of time, the past present and future, exists in a four-dimensional chunk of spacetime known as the block universe. (You can read more in the article What is a block universe?)

In a block universe, there is no special preference for "now", and no clear delineation between the past and the future. Both the future and the past already exist and "now" is any coordinate along the time dimension in the four-dimensional block of spacetime. This seems to counter our every day experience of time only ever moving forward, the past fixed and untouchable behind us, the unknown future unravelling before us dependent on the events that are happening right now. Moreover, the mathematical laws that govern the block universe are symmetrical in time: "In fundamental physics there is no explanation for why time is moving forward," says Marina Cortês, a cosmologist from the Royal Observatory, Edinburgh.

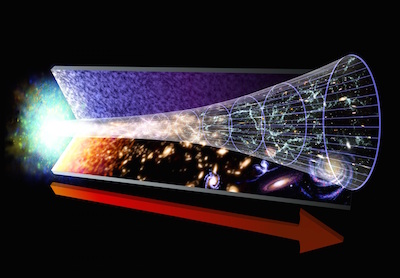

The Universe evolved from the Big Bang – a very special starting point

Instead, assuming the block time view is correct, our experience of forward progression of time can be explained by our Universe starting in a very special and unlikely state– the Big Bang – and the implications of the second law of thermodynamics. To understand this, Cortês compares the conditions of the Big Bang to a room where, instead of being spread homogenously around the room, all the oxygen molecules are compressed into a tiny space in the corner. It is very unlikely for the molecules to be in this highly-ordered state. And so, thanks to the second law of thermodynamics, the molecules will inevitably move to more likely, disordered states, spreading around the room. There's no going back to their unlikely beginnings. (You can read more about time symmetry and the second law of thermodynamics in the article Time in a block universe.)

This reliance on the fact that our universe began from a very unlikely state, leads Cortês to compare the explanation to shoving the problem of the arrow of time under the rug. "The problem is that's saying the arrow of time is only an illusion because it comes from those very special initial conditions," says Cortês. And those special initial conditions are very unlikely indeed – Cortês estimates that there were around 1090 ways the Universe could have started, and only one of these states, the Big Bang, gives rise to our Universe. In fact, for all the other possibilities we wouldn't be here. This translates to a chance of 10-90 of a universe beginning in the conditions of the Big Bang, or 0.000..00001%, where there are 89 zeros between the decimal place and the 1.

"I mean 10-90 – it's almost impossible to realise how unlikely that is."

More than puppets

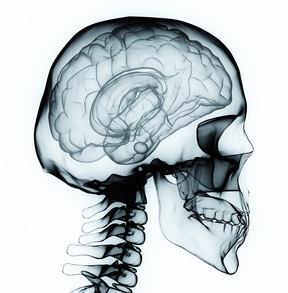

And what of free will? Block time says that our feeling that we have choice in our lives is also an illusion. "The block universe says that we're mere puppets living our lives, the play has already been written," says Cortês. But there is a possible explanation for this too. Our perception of free will could be the result of the dramatically different levels of complexity between the system in which the general relativity operates – which involves fundamental aspects of the universe such as the four dimensions of spacetime and the shapes this fabric takes – as opposed to the level of complexity of the system where free will appears to operate – the human brain.

A very complex system

"The brain is such a different regime from the regime of complexity of the system we are studying," says Cortês. "There's just spacetime, these very elementary parts of nature, and we know the laws there. You are in physics. You go a little bit higher in complexity when you go to chemistry. And then a bit higher in complexity when you go to the regime of biology, the arguments will become more and more complex, and then you are studying the human brain."

Cortês says that we can't attempt to understand the human brain using fundamental physics. "It's like saying, imagine you are a medical doctor in some emergency room… and instead of using the laws that are available in medicine, you're going to use the fundamental laws for the motion of fermions, electrons moving around in spacetime. Then the doctor can't do anything because they are not treating fermions, they are treating a patient." It seems that the same laws do not rule all levels of complexity. Most physicists would be fearful about saying something about free will in our brains that was deduced from the very elementary laws of physics, because the difference in complexity of these two systems is very large. "It's not that there are no implications [of the fundamental laws] in these different systems. But we must be careful that we are describing very different regimes of physics with the same laws – it's always dangerous when trying to apply laws beyond their regime of validity."

The future is time

Block time arises from one of the most successful scientific theories – Einstein's general theory of relativity. But its counter-intuitive implications – that time and free will are illusions – have led Cortês and others to question this view of the Universe.

"As physicists we are used to saying, don't let your perceptions influence your science too much. But there's a point where we have to say hold on, the theory we came up with makes no sense. It's refuting our most basic experience of nature; there's nothing more basic than time ticking, always passing forwards. And even more, I think the future hasn't happened yet. I want to create something with my actions; and if a theory says, no, [the future has] already happened, then to me, what it's saying is, why don't I go and lie down on the couch?"

You can read about the alternatives theories where time is fundamental in the next article.

About this article

This article is part of our Stuff happens: the physics of events project, run in collaboration with FQXi. Click here to see more articles and videos about time and the block universe.

Rachel Thomas is Editor of Plus. She interviewed Marina Cortês in April and August 2016.