Maths in a minute: Euclid's fourth axiom

Over 2000 years ago the Greek mathematician Euclid of Alexandria established his five axioms of geometry: these were statements he thought were obviously true and needed no further justification. The first three are indeed pretty obvious (see here) postulating, for example, that through any two points there is a straight line. The fourth one, however, sounds a bit weird. It says:

All right angles are equal to each other.

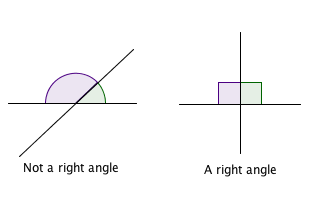

This statement seems pretty vacuous: a right angle is a 90 degree angle, and obviously all 90 degree angles are equal. But we can understand Euclid's need for stating this fact when we consider that he didn't describe right angles in terms of degrees or any other angle measure (he didn't have one). Instead, he defined them in terms of a geometric picture: if two lines intersect, and the two angles formed by that intersection are equal, then that's your right angle.

Now suppose you have two angles that adhere to that definition of being right drawn on two separate bits of paper (or papyrus if you're Euclid). You might have a nagging suspicion that perhaps those two angles are different from each other. The fourth axiom says that they're not. Those right angles are in fact equal in the sense that you could move one of them on top of the other so that they perfectly align. Having established that fact Euclid could then go on to measure other angles in terms of right angles, for example by saying that a given angle is equal to three right angles.

You can find out more about the fourth axiom in this very interesting article.

Comments

Anonymous

Not all right angles are equal.

Rule a straight line from the centre of a circle so that it intersects and continues beyond the circumference. All four angles are right angles, but the ones outside the perimeter are not equal to the ones inside. Superposition will show that they're bigger, (if you can't see that at a glance).

Euclidean geometers however only recognise angles between straight lines.The concept of an angle between a straight line and a curve is effectively disallowed by redefining it as between the straight line and the straight line tangent to the curve. Only then can you say all the right angles are equal. An arbitrary ruling which if dispensed with might mark the long awaited departure from Euclid. (Those three right angles of a triangle bounded by great circles on a sphere are in fact angles between planar sections).

Note the axioms or postulates as set out in the Scientific American link. The first three are in the imperative grammatical form, as maybe the controversial 4th and 5th should be. They're not everlasting truths, or even meant to be, but instructions on how to do a certain kind of geometry.

Let me turn to Common Notion 1 of Euclid: "Things which are equal to the same thing are equal to each other". Ever been in an office where no-one can ever find the master for re-photocopying? You keep photocopying photocopies of photocopies and end up with a mess. Same with continually measuring off a length of say rope against the previous one you've measured off. Drift or error is bound to set in after a while if you don't do it against one template length. Practical instruction again, rather than inert truism.

Cecil Burrow

> Euclidean geometers however only recognise angles between straight lines.

Geometers in general only recognize angles between straight line - the angle between curves is typically defined as the angles between their tangent lines. Understood this way, the example of a diameter cutting a circle is *not* a counterexample to the postulate in question.

Anonymous

All right angles ARE equal, even if you bisect a circle. The angle between the curve and the line is defined to be the angle between the bisecting line and the tangent to the curve at the point of intersection. The subsequent right angles formed are all equal. No other definition of determining the angle between two lines (curved or straight) makes sense.

Your example of photocopying photocopies is not relevant. Photocopies are not perfect copies, so of course over time they will become more distorted from one another. Geometrical objects do not behave like this: they are perfect in that sense.