The politician Douglas Carswell (UKIP) has recently been arguing with the scientist Paul Nightingale about what causes the tides on Earth. Carswell said it was the gravitational influence of the Sun and Nightingale said it was the Moon. The debate came up in the context of Brexit. Using the tides as an analogy, Nightingale had argued that trade relationships with the EU were more important than those with more distant giants like China.

Giving Carswell the benefit of the doubt (after all, hundreds of years' worth of expert opinion might be wrong) we decided to do a back-of-the-envelope calculation to see who's right.

Let's write $m_E$ for the mass of the Earth, $m_M$ for the mass of the Moon, and $d_M$ for the distance between Earth and Moon, measured centre to centre. Newton's universal law of gravitation tells us that the gravitational force $F$ between the two is

$$F = G\frac{m_Em_M}{d_M^2},$$

where $G$ is the gravitational constant.

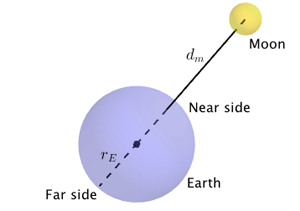

However, the tidal force the Moon exerts on the Earth is calculated by working out the ratio between its gravitational pull on the near side of the Earth and its pull on the far side.

Diagram not to scale.

To get the distance between the near side of the Earth to the centre of the Moon, we need to subtract the radius of the Earth, $r_E$, from $d_E.$ The gravitational pull of the Moon on the near side of the Earth is then

$$F_{near} = G\frac{m_Em_M}{(d_M-r_E)^2}.$$

Similarly, to get the distance between the far side of the Earth to the centre of the Moon, we need to add the radius of the Earth, $r_E$, to $d_E.$ The gravitational pull of the Moon on the far side of the Earth is then

$$F_{far} = G\frac{m_Em_M}{(d_M+r_E)^2}.$$

The ratio between the two forces is

$$\frac{F_{near}}{F_{far}} = \frac{Gm_Em_M}{(d_M-r_E)^2}\times \frac{(d_M+r_E)^2 }{Gm_Em_M} = \frac{(d_M+r_E)^2 }{(d_M-r_E)^2}.$$

Now is the time to look up some values. A quick internet search suggests we use the following:

$$d_M = 384,400km,$$

$$r_E=6371km.$$

Substituting these into our equation for the ratio gives

$$\frac{F_{near}}{F_{far}} =\frac{(384,400+6371)^2}{(384,400-6371)^2}=1.068.$$

This means that the gravitational pull of the Moon is $6.8\%$ stronger on the near side of the Earth than it is on the far side.

Now let's do the same for the Sun, writing $d_S$ for the distance between Earth and Sun, centre to centre.

By the same argument as above the ratio between the gravitational influence on either side of the Earth is

$$\frac{F_{near}}{F_{far}} = \frac{(d_S+r_E)^2 }{(d_S-r_E)^2}.$$

The value of $d_S$ can be taken as

$$d_S = 1.5 \times 10^{8}km,$$ so we get

$$\frac{F_{far}}{F_{near}} = \frac{(1.5 \times 10^{8}+6371)^2 }{(1.5 \times 10^{8}-6371)^2}=1.00017$$

This means that the gravitational pull of the Sun is only $0.017\%$ stronger on the near side of the Earth than it is on the far side.

We therefore conclude that Nightingale is right. The ratio is far bigger for the Moon than it is for the Sun, so the tides we see are due to the Moon.

Comments

Anonymous

Interesting and fun to read.