Invisibility cloaks

This article is part of our package on the maths of materials, which is based on a talk in Chris Budd's ongoing Gresham College lecture series. You can see a video of the talk below.

Many of us will have watched Harry Potter films, or maybe are fans of Star Trek. Both of these contain devices for making you invisible. In the case of Harry Potter a special cloak, and for Star Trek the infamous cloaking device.

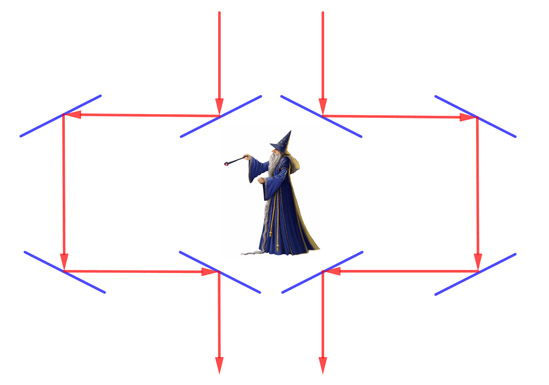

Once thought just to be the product of the imagination, invisibility cloaks are getting closer to becoming reality due to the modern science of meta-materials. Early invisibility devices used a combination of lenses and mirrors to bend the light around an object to make it appear invisible, as shown below. Making these required a knowledge of geometrical optics, and in particular the mathematics of angles and trigonometry.

In this example the incoming light rays (red) are guided by mirrors around the wizard in the middle of the diagram. The wizard would therefore appear invisible to an onlooker seeing the outgoing light rays — all they would see is the area behind the wizard as reflected by the mirrors.

However these cloaking devices could only work when viewed from one direction, so there has been intensive research into finding materials which can cloak someone when viewed from many directions. Researchers in the US have now invented a digital cloaking device that does work from many different directions, and which, despite some short-comings, suggests such technology may be ready for practical uses in the real world sooner than you might think.

The reason why we can see an object (or person) is that light rays that encounter it are obstructed and reflected by it. The system developed by the US researchers calculates the direction and position of those light rays and then displays them as if they were unobstructed. As a result, the area behind the display is effectively cloaked. As the viewpoint shifts, the image on the display changes accordingly, keeping it aligned with the background.

Invisibility cloaks themselves rely on meta materials, which have been engineered to produce properties that don't occur naturally. Light is electromagnetic radiation, made up of vibrations of electric and magnetic fields. Natural materials usually only affect the electric component, but meta-materials can affect the magnetic component too, expanding the range of interactions that are possible. The meta materials used in attempts to make invisibility cloaks are made up of a lattice with the spacing between elements less than the wavelength of the light, which can then be bent by the material.

A related development has been the design of clothing which is not only flexible to fit the body, but also has the properties of LCD screens (see Crystal clear to find out more). By using these materials we can envisage a future where the colour of a dress or a suit can be instantly changed to meet the needs of an event, and can even display moving writing if a sponsor desires it. Maths meets fashion indeed.

You can read more about invisibility cloaks on Plus.

About this article

This article is based on a talk in Budd's ongoing Gresham College lecture series. A video of the talk is below.

Chris Budd.

Chris Budd OBE is Professor of Applied Mathematics at the University of Bath, Vice President of the Institute of Mathematics and its Applications, Chair of Mathematics for the Royal Institution and an honorary fellow of the British Science Association. He is particularly interested in applying mathematics to the real world and promoting the public understanding of mathematics.

He has co-written the popular mathematics book Mathematics Galore!, published by Oxford University Press, with C. Sangwin, and features in the book 50 Visions of Mathematics ed. Sam Parc.

This article now forms part of our coverage of the cutting-edge research done at the Isaac Newton Institute for Mathematical Sciences (INI) in Cambridge. The INI is an international research centre and our neighbour here on the University of Cambridge's maths campus. It attracts leading mathematical scientists from all over the world, and is open to all. Visit www.newton.ac.uk to find out more.