Maths in a minute: The Poincaré conjecture

Brief summary

We look at the Poincaré conjecture from topology, which drove the field for the best part of the twentieth century. It concerns the question of how to recognise whether a shape is a topological 3-sphere.

The Poincaré conjecture taunted mathematicians for nearly 100 years until it was resolved in the 2000s by the Russian mathematician Grigory Perelman. It concerns the three-dimensional sphere, also called the 3-sphere, a shape we can't actually visualise.

Now you see it…

So let's start by thinking of the ordinary sphere we know and love. It is a surface (a two-dimensional shape) which sits in three-dimensional space. To a geometer the sphere is precisely defined as all the points that lie a fixed distance (the radius of the sphere) from a given centre point.

Topologists, however, are more lenient. In topology two objects are considered equivalent if you can morph one into the other without cutting or gluing. Hence, the shell of an egg or a knobbly potato are also considered spheres in topology.

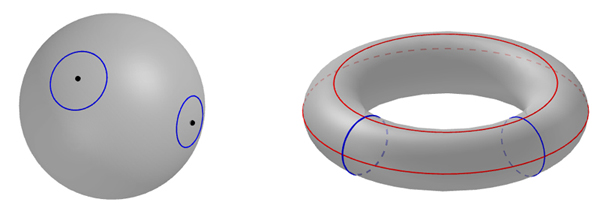

There are lots of other surfaces too besides the sphere. An example is the surface of a doughnut, mathematically known as the torus. That's clearly not topologically equivalent to a sphere because it has a hole. To turn it into a sphere you'd have to cut it open and glue the newly created edges together in an appropriate way.

How do we identify which other surfaces are topologically the same as the sphere and which are not?

Firstly, we can rule out surfaces that have an edge, such as a disc. You'd have to glue this edge together somehow to form a sphere. We can also rule out surfaces that are infinite in extent. In fact, we will only consider surfaces that are compact, which means that they could be assembled by stitching together a finite number of overlapping patches. We will also rule out strange surfaces like the Möbius strip, which haven't got a clearly defined inside and outside — these are called non-orientable. In short, we will only consider surfaces that are closed (they are compact and don't have an edge) and orientable.

Given a compact and orientable surface without an edge, it turns out that holes are the only things that can stop us from turning it into a sphere. It can be proved that such a surface is topologically equivalent to a sphere if and only if it has no holes.

…now you don't — but don't worry

The 3-sphere sits in four-dimensional space. Like the 2-sphere it consists of all the points that sit at a fixed distance from a given centre point. To find out more about how it is defined see this article. There is also an analogue of the notion of surfaces: 3-manifolds are three-dimensional shapes sitting within four-dimensional space. See here for a definition of manifolds.

The Poincaré conjecture concerns the same question we just considered for the ordinary 2-sphere: how can we tell that a 3-manifold is topologically the same as the 3-sphere? Taking inspiration from the dimension below, we might hazard the guess that it's exactly those that are closed and don't have holes.

What, though, is a hole? So far we have relied on the fact that we can see the holes, as is the case with the torus, but how do you define holes when you can't visualise the shape that has them?

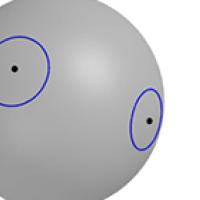

Luckily there is a neat way of answering this question. Thinking of ordinary surfaces, it's not hard to convince yourself that if a surface has no hole, then any loop you can draw on it can be continuously contracted to a point without cutting (technically, any loop is homotopic to a point). You don't have to cut the loop to do this. This isn't true for a surface that has a hole. If the loop winds around the hole there's no way you can contract it to a point. Surfaces without holes are exactly those on which any loop can be contracted to a point. And if such a surface is also closed and orientable, then it is topologically equivalent to a 2-sphere.

It is also possible to conceive of the concept of a loop sitting on a 3-manifold, and of the action of contracting this loop to a point. In 1904 the French mathematician Henri Poincaré conjectured that if all loops on a closed 3-manifold can be continuously contracted to a point, then the manifold is topologically equivalent to a 3-sphere.

A hundred years of proof searching

That's in direct analogy to what happens in the dimension below, which we can still visualise, so you might think the result should be easy to prove. Alas, it was not. Much of 20th century effort in topology was focussed on proving the Poincaré conjecture. Success finally arrived in the early 2000s when the Russian mathematician Grigory Perelman published three papers which proved the conjecture (in fact they proved a more general result, called Thurston's geometrisation conjecture, named after the mathematician Bill Thurston). Perelman was awarded a Fields Medal, one of the most important prizes in mathematics, for his work in 2006, but refused to accept it.

Since the Poincaré conjecture was so hard to prove for 3-spheres living in four-dimensional space, you'd think that higher dimensions would pose even more of a problem. But oddly, this isn't the case. Generalised versions of the Poincaré conjecture for spheres of dimensions 4 and higher were proved quite a while before Perelman came up with his proof for the 3-sphere — in the 1960s for spheres of dimensions 5 and above and in the 1980s for spheres of dimension 4. Three Fields medals were awarded for the effort: to John Milnor, Steve Smale, and Michael Freedman. (You can read a brief history of the generalised Poincaré conjecture on Wikipedia.)

About this article

This article was produced as part of our collaboration with the Isaac Newton Institute for Mathematical Sciences (INI) – you can find all the content from the collaboration here.

The INI is an international research centre and our neighbour here on the University of Cambridge's maths campus. It attracts leading mathematical scientists from all over the world, and is open to all. Visit www.newton.ac.uk to find out more.