Post-quantum cryptography

Our digital, networked lives are only possible thanks to cryptography – the science of keeping information secret. It is used in our web browsers when we shop online to protect our credit card details from thieves. The banking network needs cryptography to keep financial systems secure so that someone can't hack in and edit your transaction history to change the £2.50 you spent on your morning coffee to £2.5 million. Even the mobile phone network uses cryptography to stop your phone from interfering with the radio frequencies of other phones and devices around you.

Ingenious uses of maths have provided the key to cryptography so far, but quantum computing could make our current techniques useless. How can we prepare for this quantum future and ensure we can continue to live our digital lives?

This was one of the key questions being discussed at an event Quantum Computing: Applications and Challenges organised by the Newton Gateway to Mathematics, held as part of a longer research programme at the Isaac Newton Institute for Mathematical Sciences in Cambridge.

Quantum danger

The foundation of all internet security is something called public-key cryptography. (You can read an easy introduction to this idea here.) The public-key cryptography systems used today are currently secure, even when attacked by the fastest computers. This is because the cryptographic standards get strengthened as computing power increases. For example the RSA system relies on the fact that it is very hard to factor very large numbers. In 2007, to maintain security despite the advances in computing power, the recommended standard for RSA moved from using numbers with over 300 digits to numbers with over 600 digits.

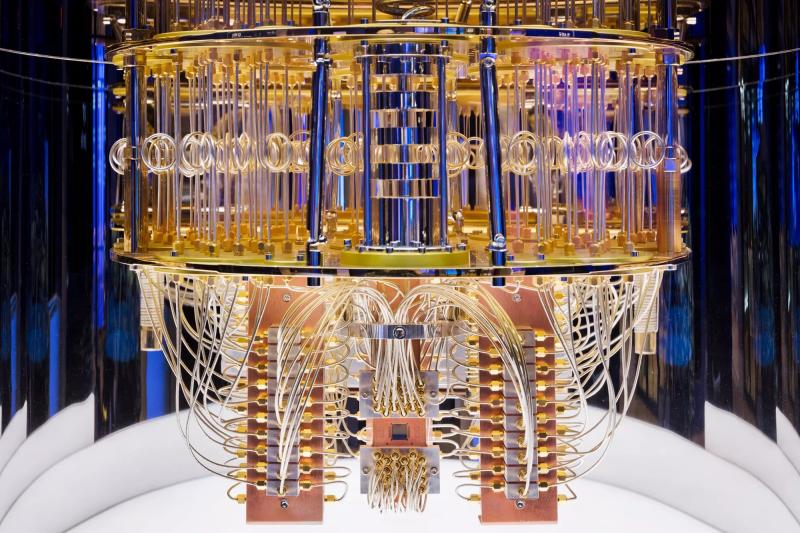

But current cryptographic techniques will be at risk when quantum computers become more useful and more available, said Zygmunt Lozinski from IBM Research, one of the speakers at the event. "Suppose we had a large scale quantum computer – what are the implications for that for our networks?"

The problem is that quantum computers operate in a very different way to classical computers, which means that you can write very different algorithms for solving mathematical problems on quantum computers. In 1994, seemingly out of the blue, the American mathematician Peter Shor came up with a famous algorithm which can in theory break the RSA system. "I don't know how he did it," Lozinski said. "He came up with the idea that if you had a quantum computer, which didn't exist in 1994, it would allow you to break RSA really quickly."

Even though there aren't quantum computers capable of running Shor's algorithm yet, protecting our networks against this potential quantum danger is already important. "It takes a long time to update technology and networks – 10, 20, even 50 years," Lozinski said. And as well as protecting future networks against attacks by quantum computers, the data in our networks today is already at risk.

If data is valuable it could be stolen now in its encrypted form, with the intention of holding onto the data until it is possible to decrypt it in the future when quantum computers are available, explained Lozinski. (This is something called a harvest now - decrypt later attack.) For example the encrypted details of a drug in development today or the design of a new aircraft engine might be worth billions of pounds if it can be decrypted and used by competitors in the future.

Of course some information is always publicly available, but we rely on cryptographic techniques to keep it secure against any interference. "If you own a house or flat that exists as a record in the land registry database in Plymouth and that is secured by public key cryptography," Lozinski said. "If I could change that record that would be a tragedy for you. But if I can change that record for [thousands of] people that could cause a global infrastructure crisis."

But not all hope is lost. The good news is that maths can provide a cryptographic system that can't be broken, even by quantum computers.

Lattice-based cryptography is the key

The public-key cryptography of RSA and elliptic cryptography rely on having a mathematical problem that is easy to calculate in one direction but hard to solve in the other. For RSA cryptography the easy to calculate problem is multiplying two numbers together – this is the part of RSA that metaphorically snaps the padlock shut on your message. And the hard to solve problem is factoring a large number – the prime factors providing the key to unlock the mathematical padlock.

For post-quantum cryptography we need a mathematical problem that even a quantum computer cannot solve (to the best of our knowledge). And the top current candidate is based on the mathematics of lattices.

This time the mathematical padlock is a bit harder to describe than it was for the RSA system. You can think of a two-dimensional lattice as a grid of dots on an infinitely large page. Now rather than a 2D grid on a page, mathematics gives you a way to work with very high-dimensional lattices. These high-dimensional lattices might have hundreds, or even thousands, of dimensions. (You can read an introduction to lattices here, and an introduction to the idea of higher dimensions here.) Lozinski described lattice based cryptography as "finding a needle in a haystack". You encrypt your message by putting it within the high-dimensional lattice – the haystack. Then your message is as hard to find as the proverbial needle, unless you have some key piece of information. (You can find out more in our introduction to lattice-based cryptography here.)

Lattice based cryptography is currently one of the best candidates for keeping our information safe in the age of quantum computing. Three of the four algorithms that NIST (the US National Institute of Standards and Technology) are standardising for use in post-quantum cryptography are lattice based. (You can find the technical details on the NIST website, where they also have this excellent plain language summary of this work.) "But there are no guarantees", said Petros Wallden, from the Quantum Software Lab at the University of Edinburgh. "Post-quantum cryptography needs the same scrutiny as classical cryptography."

Cryptographic agility

The reason we trusted classical cryptography such as RSA is that a community of experts and researchers keep trying to break it. But despite years of work and increases in (classical) computing power, only small advances have been made in cracking these classical cryptographic systems. "To establish the same confidence in quantum cryptography we need the cryptanalysis community to do the same thing," said Wallden, in his talk at the Newton Gateway event. "We need expertise in quantum algorithms and cryptography to scrutinise post-quantum cryptography."

Currently, though, there are not many people with all the necessary skills. Many of the speakers hoped that this event, and the longer INI programme, would encourage more researchers into the area. As well as being fascinating mathematically and technically, it is also a chance to have a huge impact on our society and the way it works.

But having the right mathematical tools for post-quantum cryptography isn't enough. We can't change the locks on the world's networks overnight. The US is leading the effort so far, with funding and national plans including the work done at NIST. Now European countries are aiming to have their own plans and be ready to start work in 2026. And Lozinski and Wallden are part of the community in the UK moving things forward.

"Luckily there will not be a single 'Q-Day' where everything suddenly becomes vulnerable," Lozinski said. Large-scale quantum computers may start coming online in the next decades, but only a few at a time. And these initial quantum computers will probably be focussed on very high-value research that can't be feasibly done in other ways, such as modeling the reactions inside electric vehicle batteries or folding proteins. But the consensus is that quantum computers capable of breaking classical cryptography will eventually become available in the future. "We need policy makers and industry not to kick the can down the road, and identify what interventions are needed today. There's a huge amount of work to be done."

Ultimately, Lozinski said, we need to move towards cryptographic agility: "Just as you can replace the batteries in a torch, or plug in a new pair of headphones, we need pluggable cryptographic components in our systems." We need to learn the lessons from first implementing public-key cryptography, then realising we need to move to post-quantum cryptography, to change the way we think about keeping the world's networks safe. As Lozinski said: "It's now longer a case of do it once and it's done."

About this article

This article was based on talks by Zygmunt Lozinski and Petros Wallden at Quantum Computing: Applications and Challenges, an event organised by the Newton Gateway to Mathematics as part of the Quantum information, quantum groups and operator algebras programme at the Isaac Newton Institute for Mathematical Sciences in Cambridge.

Zygmunt Lozinski is a Senior Technical Staff Member in IBM Research, where he is responsible for making the world’s networks quantum-safe.

Petros Wallden is an associate professor at the Quantum Software Lab at the University of Edinburgh.

Rachel Thomas is Editor of Plus

This article was produced as part of our collaborations with the Isaac Newton Institute for Mathematical Sciences (INI) and the Newton Gateway to Mathematics.

The INI is an international research centre and our neighbour here on the University of Cambridge's maths campus. The Newton Gateway is the impact initiative of the INI, which engages with users of mathematics. You can find all the content from the collaboration here.