Maths in a minute: the Fibonacci sequence

Leonardo Fibonacci c1175-1250.

The Fibonacci sequence

$$1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, ...$$ is one of the most famous number sequences of them all. We've given you the first few numbers here, but what's the next one in line? It turns out that the answer is simple. Every number in the Fibonacci sequence (starting from $2$) is the sum of the two numbers preceding it: \begin{eqnarray*} 2 & = & 1 &+& 1 \\ 3 & = & 1 &+& 2 \\ 5 & = & 2 &+& 3\\ 8 & = & 3 &+& 5, \end{eqnarray*} and so on. So it's pretty easy to figure out that the next number in the sequence above is $55+89 = 144,$ and (in theory at least) to work out all numbers that follow from here to infinity.Hear the music of the Fibonacci sequence in our podcast!

Where does it come from?

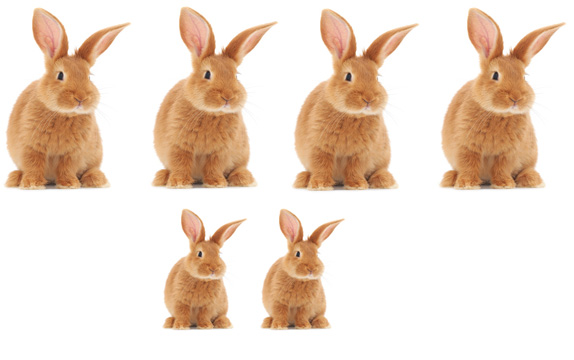

The Fibonacci is named after the mathematician Leonardo Fibonacci who stumbled across it in the 12th century while contemplating a curious problem. Fibonacci started with a pair of fictional and slightly unbelievable baby rabbits, a baby boy rabbit and a baby girl rabbit.

They were fully grown after one month

and did what rabbits do best, so that the next month two more baby rabbits (again a boy and a girl) were born.

The next month these babies were fully grown and the first pair had two more baby rabbits (again, handily a boy and a girl).

Ignoring problems of in-breeding, the next month the two adult pairs each have a pair of baby rabbits and the babies from last month mature.

Where does it go?

Real rabbits don't breed as Fibonacci hypothesised, but his sequence still appears frequently in nature, as it seems to capture some aspect of growth. You can find it, for example, in the turns of natural spirals, in plants, and in the family tree of bees. The sequence is also closely related to a famous number called the golden ratio. To find out more visit our collection of articles about Fibonacci and his mathematics. And if you'd like to hear how the Fibonacci sequence sounds you should listen to our podcast!

About the author

Rachel Thomas is Editor of Plus.

Comments

jennifer yusi

The rabit as a cover of this page, which attracts me to open the post. The number of rabbit is a good way to apply in mathmatics. That's funny!

Steve

If you start with 0 and 1 then every number after those is the sum of the two numbers preceding it.

Shariputra

The Fibonacci sequence was actually discovered much earlier by Indian poets and linguists who came across this sequence while studying Sanskrit poetry. More information on this can be found, for example, on the wikipedia page for the Fibonacci numbers: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fibonacci_number. This topic is also discussed by the Fields Medallist Manjul Bhargava in multiple lectures on YouTube.

Hence, in this article, under the heading 'Where does it come from'?, it might be pertinent to mention that this sequence was in fact discovered much earlier. This might help dispel the misunderstanding that Fibonacci was the first one to come across this sequence. It will also enrich the article by showing the readers how this sequence arose from a completely different (and surprising!) context- poetry!