The happy ending problem

The happy ending problem is one of those mathematical questions that are quite easy to explain but have as yet defied all attempts to answer them. Some of the best mathematicians in the world have put their minds to it, to no avail. It concerns points drawn on a piece of paper and the figures you can create by connecting them up.

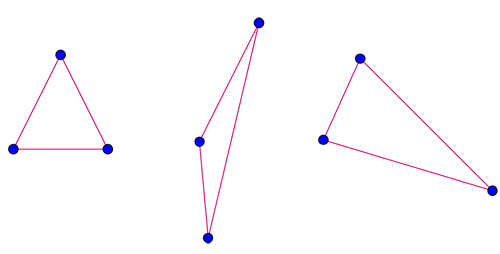

Let's start with three points, drawn on a piece of paper, that don't all lie on a line. You can always connect them up to form a triangle which has the three points as its corners:

Three points in the plane form a triangle (as long as they don't lie on the same line).

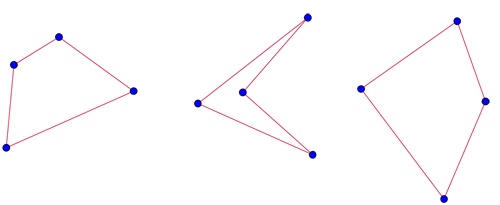

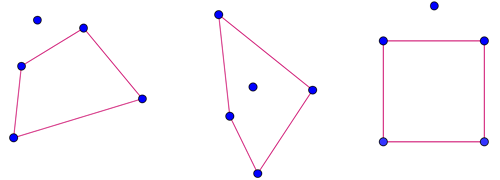

What happens when you have four points (with no three of them lying on the same line)? Connecting them you can create a four-sided figure (called a quadrilateral) which has the four points as its corners:

Some quadrilaterals.

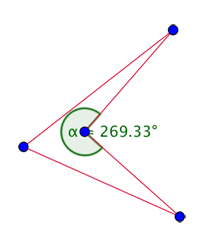

But depending on how the points are distributed, the quadrilateral might look a bit odd (like the centre one in the image above) containing dents and spikes and not at all resembling the neat and regular rectangle that first springs to mind when we think of four-sided figures. So let's impose a further restriction. Let's see if we can draw a convex quadrilateral with our four points, that is, one in which all internal angles are at most 180 degrees. This ensures the shape contains no corners that are "pushed inwards", creating a dent. The quadrilateral below is not convex, but the left and right ones in the figure above are.

A non-convex quadrilateral.

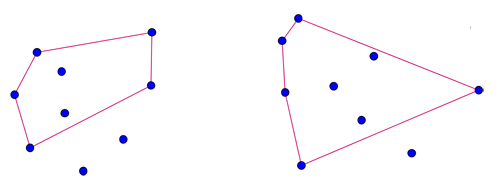

Some simple examples show that given four points, you can't always draw a convex quadrilateral:

Given four points, it's not always possible to connect them up to form a convex quadrilateral.

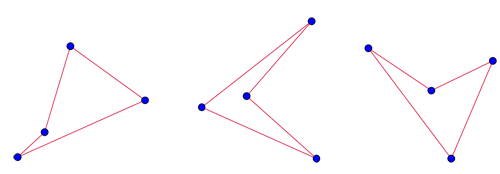

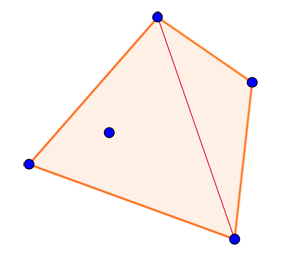

Things change, though, when you add one more point. When you have five points drawn on a piece of paper (without three of them lying on the same line), you can always connect four of them to form a convex quadrilateral. The extra point gives you just enough flexibility to do it. Here are some examples (you might actually be able to draw several different convex quadrilateral with the same five points):

Given five points (with no three lying on the same line), you can always find a convex quadrilateral which has four of them as its corners.

This result was named the happy ending theorem by the mathematician Paul Erdős, because two of his friends who worked on it, George Szekeres and Esther Klein, ended up getting married. You can see a sketch proof of this result below.

Adding sides

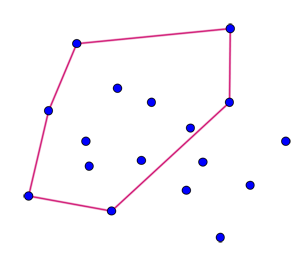

The obvious next question is how many points you need to ensure that you can connect five of them to form a convex pentagon (five-sided figure). The answer is 9 (without three of them lying on the same line). Here are two examples:

Given nine points (with no three lying on the same line), you can always find a convex pentagon which has five of them as its corners.

To be sure you can draw a convex hexagon (six sides) you need 17 points. Here's an example:

Given 17 points (with no three lying on the same line), you can always find a convex hexagon which has six of them as its corners.

The happy ending problem illustrates an interesting phenomenon: if a system is large enough (e.g. sufficiently many points) then you can hope to find some order within it (e.g. convex figures), even if the system as a whole is disordered. It's a phenomenon studied by an area of maths called Ramsey theory. You can find out more in the Plus article Friends and strangers.

Sketch proof of the happy ending theorem for n=4

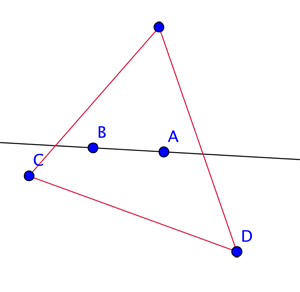

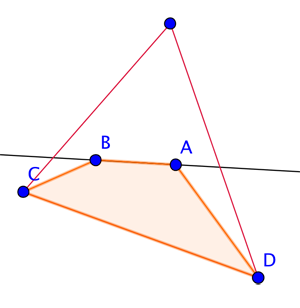

Suppose you have five points in the plane. Let's first suppose that three of these points can be connected up to form a triangle that contains the two remaining points, call them $A$ and $B$, in its interior. The line that connects these two interior points cuts the triangle into two parts. One piece only contains one of the triangle's corners, and the other contains two: call these two corners $C$ and $D$.

The triangle cut in two pieces.

At least one point lies outside of the triangle.

About the author

Marianne Freiberger is Editor of Plus.

Comments

Giorgio Antonelli

Let's see if we can draw a convex quadrilateral with our four points, that is, one in which all internal angles are at most 180 degrees.

I think 180 was meant to be 360.

Rachel

The internal angles of any convex polygon are at most 180, otherwise it would be concave.

puzzlemaker3

No, each internal angle of any convex polygon is not at most 180 degrees. That would mean they could be 180 degrees. Every n-sided convex polygon has n internal angles, and each of them is less than 180 degrees. "At most" means "less than or equal to," and that is false here.

danlboon

I believe that a polygon with a 180 degree angle would still be considered convex. In general, a convex region is defined as a region where the line segment connecting any two points in he region falls entirely within the region. In any case, the Happy End problem was originally considering a set of points in the plane in "general position", which meant that no three points were co-linear. In such a case, there could be no 180 degree angles.

Jay Hurley

I think I solved this problem for 7-gon, and on the path to a provable formula for n-gon.