Maths in a Minute: the Leaning Tower of Lire

Do you have a memory of, at sometime in your life, fidgetting with a tower of coins? It might have been while counting up your personal piggy bank, or perhaps while working the till at Mr Jones’ corner shop that was down the road. If so, you might have tried to lean your pile of coins. You might have stacked them off-center to see just how far you could lean it. So, that’s the question for this article, how far could you have leant it?

The first record of this problem comes from a 1955 article by Paul B. Johnson titled Leaning Tower of Lire, (lire being the plural of lira, the currency of Italy at the time). He begins the article: “Every miser knows that a stack of pennies can be ‘leaned’ slightly off vertical without falling. How far can the top penny be from its position in a vertical stack?”

Suppose that we have some identical rectangles, all of length 2 (the height of these rectangles is irrelevant for the purposes of this problem), with the centre of mass of each rectangle being in the middle of the rectangle (at a distance of 1 from either side). One might imagine these rectangles as the side view of the coins. We want to stack these rectangles over a ledge, such as the edge of a table. (For simplicity, we assume that only one rectangle is used at each vertical level.) The problem is, given the availability of an arbitrary number of rectangles, how much overhang over the ledge is possible?

Before discussing the solution, what does your intuition tell you? Could an overhang of 2 (an entire rectangle length) over the ledge be achieved? How about 4, 6 or 100? The answer to all these questions, perhaps unintuitively, is yes. It turns out that an arbitrarily large overhang is possible.

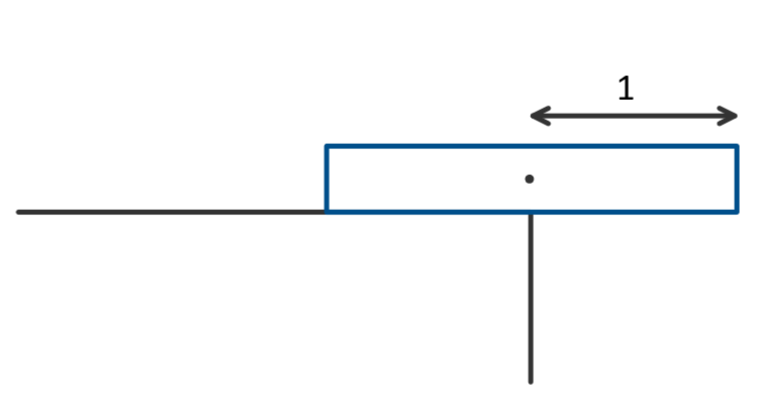

Let’s begin with a single rectangle. The maximum overhang we can get is a length of 1 as this is when the centre of mass of the rectangle lies vertically above the edge. Any further and the rectangle topples over to the floor. (Technically, this is because the gravitational force generates a torque around the edge, causing the rectangle to topple to the floor).

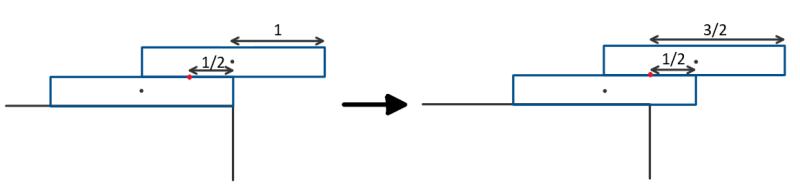

Now, introduce a second rectangle underneath the first. The top rectangle has a maximum overhang over the bottom rectangle of 1, but now we can slowly push the second rectangle further over the edge. We can do this until the combined centre of mass of the two rectangles is directly above the edge.

We now need a quick aside on how to find the centre of mass (CoM). Imagine holding two identical tennis balls, one in either hand. Where is the centre of mass of these two balls? Hopefully, it is intuitive that it must lie exactly halfway between the two tennis balls. In other words,

$\text{CoM}=\frac{1}{2}(\text{Position of tennis ball 1} + \text{Position of tennis ball 2})$

Similarly, if there are three tennis balls, the centre of mass would be:

$\text{CoM}=\frac{1}{3}(\text{Position of tennis ball 1} + \text{Position of tennis ball 2} + \text{Position of tennis ball 3})$

That is, if we have objects with the same mass, the centre of mass of them all is just the mean of their positions. (By "the position of an object", we specifically mean "the position of the centre of mass of an object").

This means that if we want to calculate the centre of mass for an ensemble of rectangles, we merely must take the mean of their respective centres of mass.

So, now let’s work out the centre of mass of the two rectangles as in the diagram above. Let's measure distance as distance over the edge. So, if we are distance 1 over the edge, that is distance +1, and if we are distance 1 before the edge, that is distance -1. Then, this would mean that, as we can see in the diagram,

$\text{CoM} = \frac{1}{2}(0 + (-1)) = -\frac{1}{2}.$

So, by slowly pushing the bottom rectangle, we can get a total overhang of

$1+\frac{1}{2} = \frac{3}{2}.$

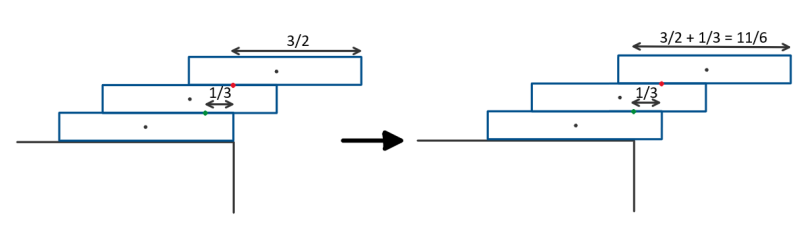

To introduce the third rectangle, we do the same. Put the two original rectangles on top and push out the bottom one until the centre of mass of the combined system lies on the edge.

Again, the centre of mass is just the mean,

$\text{CoM}=\frac{1}{3}(\frac{1}{2} + - \frac{1}{2} + -1) = -\frac{1}{3}$.

So we can get an overhang of

$1+ \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{3} = \frac{11}{6}$.

This pattern continues. Suppose we've already stacked $n-1$ rectangles and we want to add one more. We put a rectangle underneath and push it until its centre of mass is on the edge. Now, note that the centre of mass of the top $n-1$ rectangles already lies directly on the edge, (we pushed it to the edge when we added the most recent rectangle). That is, the mean of the position of their centres of mass is 0, i.e. the sum of the positions of their centre of mass is 0. So, the centre of mass of the whole system is

$\text{CoM}=\frac{1}{n}[ (\text{terms that sum to 0}) + -1] = -\frac{1}{n}$.

So repeating this process of inserting rectangles beneath and slowly pushing them as far as possible, after $n$ rectangles are used, we get an overhang of

$1+\frac{1}{2} +\frac{1}{3} +\frac{1}{4} +\frac{1}{5} +...+\frac{1}{n}.$

This is known as the harmonic series. This is a series that crops up all over maths, in counting primes, analysing algorithms and even the harmonics of music (hence the series' name.) You can read more about it in this article as well as on Wikipedia.

What is particularly interesting about it, which you can read about in the sources linked in the paragraph above is that as $n$ tends to infinity, the sum also tends to infinity, albeit slowly. That is to say we can get an arbitrarily large overhang. If they so wished, the miser's leaning tower of lire could extend from anywhere to Pisa!

About the Author

Ben Watkins finished his 4th year of mathematics at Cambridge in 2025. His interests include theoretical physics, quantum computation, and mathematical communication: sharing the joy of maths with a wider audience!