Maths in a minute: What types of numbers are there?

In this article we will have a quick look at some important groups of numbers.

Natural numbers

The first mathematical thing we learn to do in our lives is count — that is, we learn about the integers 1,2,3,4,5, etc. These numbers are also called the natural numbers. They go on forever: no matter how large a number you have reached, you can always add 1 to get an even larger number. You can visualise the natural numbers as lying along a ruler that is infinitely long, each natural number a distance of 1 from the previous one.

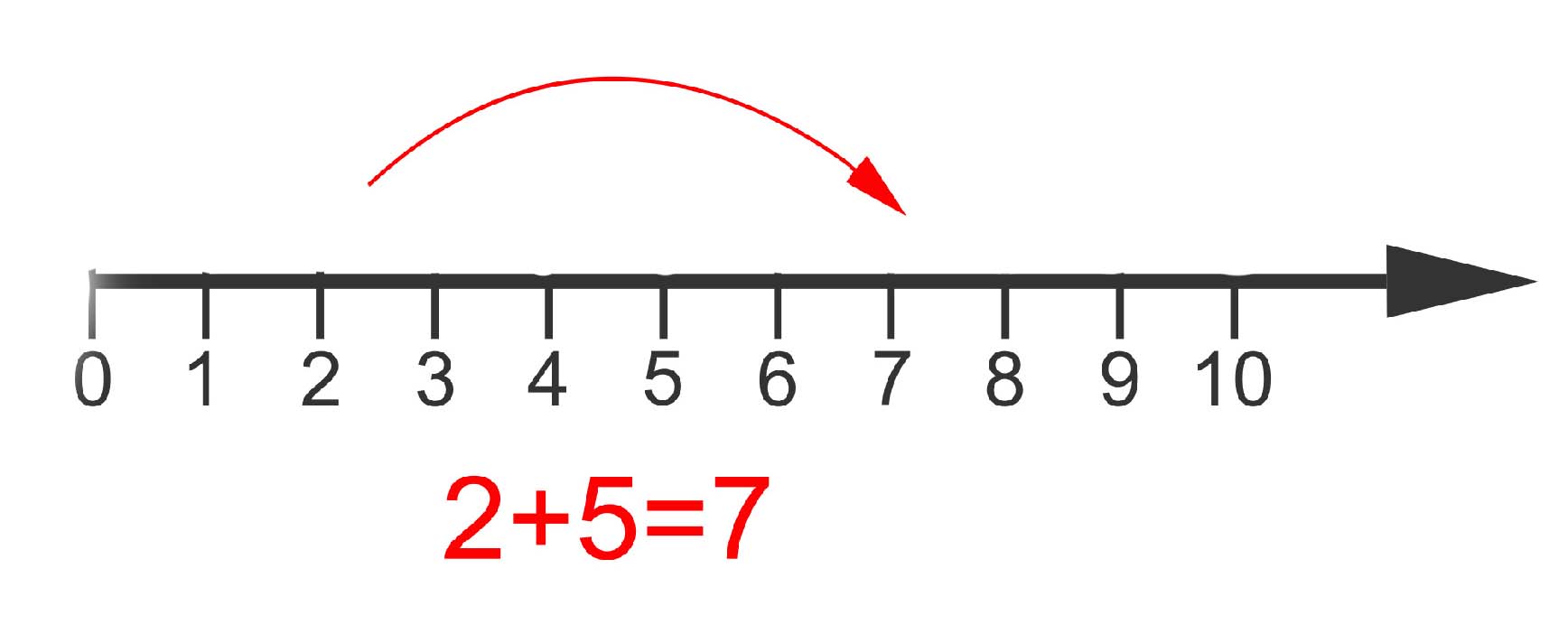

Adding a natural number m to a natural number n corresponds to taking m steps to the right on this number line, starting from n. Subtracting a natural number m from a natural number n corresponds to taking m steps to the left on this number line, starting from n.

Some mathematicians include the number 0 in the set of all natural numbers and some don't. It's a matter of preference. The set of all natural numbers is usually denoted by the symbol $\mathbb{N}$.

Negative numbers

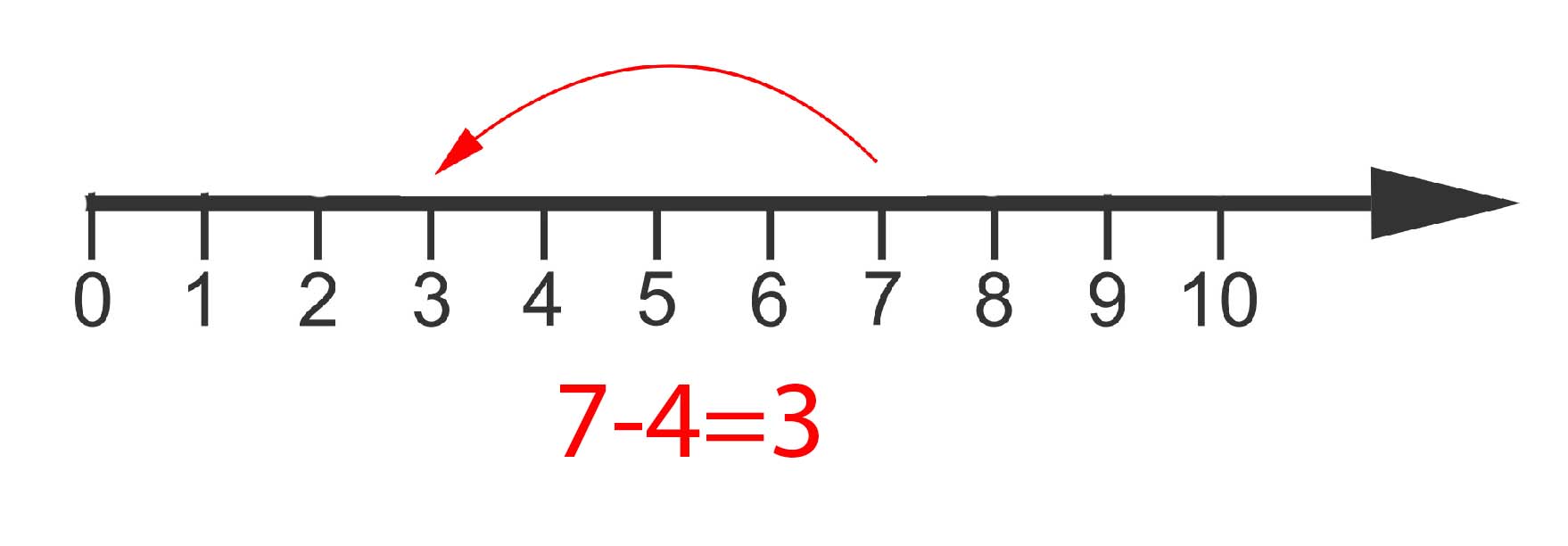

The number line as shown above illustrates a problem. What if I want to subtract 5 from 3? If I start at 3 and take 5 steps to the left I run out of number line after 3 of those steps. What to do?

The answer comes from the negative numbers, -1, -2, -3, etc. These lie along a second piece of the number line, extending infinitely from 0 towards the left:

We can now happily subtract 5 from 3: it lands us at -2. Indeed, the operations of addition and subtraction allow us to move along the number line right and left to our heart's content. To find out more about how to do arithmetic with all the integers, positive and negative, see this website.

The set of all the integers together, zero, positive and negative, is denoted by $\mathbb{Z}.$

Rational numbers

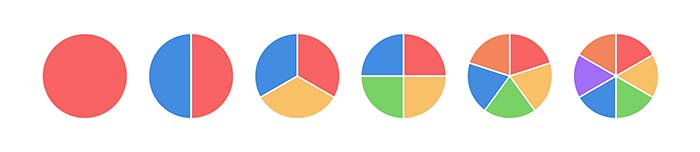

As you grow up, as well as learning to do basic arithmetic, you also encounter one of life's most uncomfortable facts: that sometimes you have to share things. This means you'll encounter fractions, also called rational numbers. If you share a cake equally between two people, then each gets 1/2 of the cake. If you share equally between three, then each gets 1/3 of the cake, and so on.

Each of 1/2, 1/3, 1/4, etc is a rational number, but generally rational numbers don't have to be a 1 up top. The numbers 3/4, 4/7, and 456/789 are also rational.

Generally, rational numbers are those that come from dividing one integer by another so they can be written as m/n where m and n are both integers. The top integer, m, is known as the numerator and the bottom integer, n, is known as the denominator. In terms of pieces of cake, the number m/n can be depicted as n pieces of an 1/mth of the cake. To find out how to calculate with fractions, see here.

Note that the natural numbers are all also rational numbers because for any number m we have m=m/1.

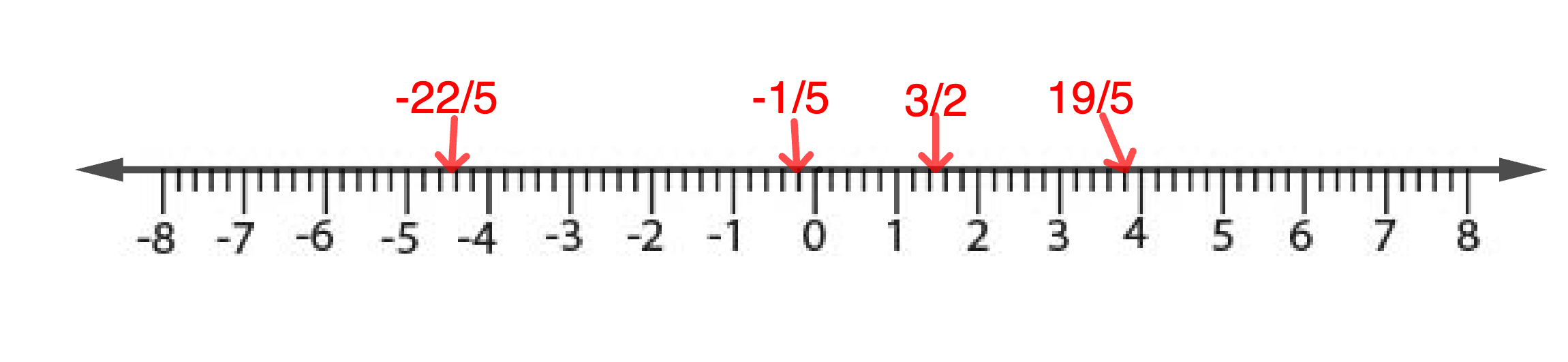

And just as there are negative natural numbers, there are also negative rational numbers, which you can find on the negative part of the number line:

Because there are infinitely many natural numbers there are also infinitely many rational numbers: there are infinitely many choices for the natural number that goes in the numerator and infinitely many choices for the natural number that goes in the denominator. In fact, given a piece of the number line, no matter how small, you can find infinitely many rational numbers within it.

The set of all rational numbers, zero, positive and negative, is usually denoted by $\mathbb{Q}$.

Irrational numbers

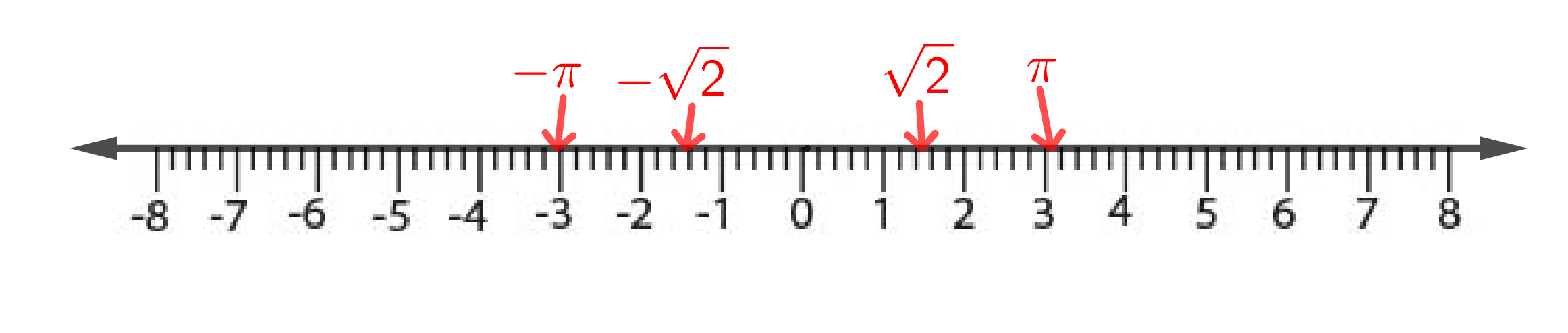

Looking at our number line above begs a question: do the rational numbers fill up all of it? The answer is "no" — if you took all the rational numbers away there would still be something left. What would be left are the irrational numbers. Since all rational numbers can be written as fractions, the irrational numbers are those that can't be written as fractions. Examples are $\sqrt{2}$ and $\pi$. (Actually the proof that $\sqrt{2}$ is irrational is one of the most elegant in mathematics, see here.)

As with the rationals, there are negative as well as positive irrational numbers.

Both rational and irrational numbers can be written using their decimal expansion (to find the decimal expansion of a fraction you need to do some long division). For rational numbers the expansion is either finite or ends in a block that repeats for ever and ever. Examples are

$1/2=0.5$ (finite decimal expansion)

$3/4=0.75$ (finite decimal expansion)

$7 1/8 = 57/8=7.125$ (finite decimal expansion)

And

$1/3=0.3333333333…$ (recurring decimal expansion)

$9/11= 0.81818181…. $ (recurring decimal expansion)

$7/12=58333333333…$ (recurring decimal expansion)

Irrational numbers, by contrast, have infinite decimal expansion that don't end in a recurring block. For example

$\sqrt{2}=1.4142135…$

$\pi = 3.1415926…$

This means you can never fully write down an irrational number — you don't have an infinite amount of time or space on the page to write all of the infinitely many digits. It also shows that there are infinitely many irrational numbers — that's because you can come up with infinitely many infinitely long decimal expansions. And just as for the rational numbers, given a piece of the number line, no matter how small, you can find infinitely many irrational numbers within it.

An interesting fact is that, although there are infinitely many rational numbers and infinitely many irrational numbers, there are, in a sense, more irrational numbers than rational ones. You can find out more in this article.

Real numbers

The rational and irrational numbers taken together fill up all of the number line and are known as the real numbers. Every real number can be represented by a (potentially infinite) decimal expansion and every (potentially infinite) decimal expansion denotes a real number.

The set of real numbers is usually denoted by $\mathbb{R}$.

Prime numbers

The prime numbers are natural numbers that deserve a special mention. They are those numbers that can only be divided by themselves and 1 (without leaving a remainder). The first few prime numbers are:

2, 5, 7, 11, 13….

Every natural number that is not a prime can be written as a product of prime numbers. For example,

6=2x3

8=2x2x2

10=2x5

Because of this the primes are known as the atoms of number theory. When mathematicians try to prove a result that involves integers, they often try to prove it for the primes first. Since all the other natural numbers are products of primes, the proof can then sometimes be extended relatively easily.

There are infinitely many prime numbers, as was proved by the ancient mathematician Euclid (you can see the proof here). How exactly they are distributed on the number line is one of the great mysteries of mathematics (find out more here). And although we know that there are infinitely many primes, we don't have a formula which tells us what they all look like. This is why mathematicians are forever searching for bigger and bigger primes (find out more here).

Complex numbers

The real numbers — including integers, rational and irrational numbers — are all the numbers we can think of intuitively. It's a useful and beautiful fact that they can be visualised as merging together to create a number line.

But if we are prepared to expand our horizon, then we can think of another class of numbers which can be visualised as filling up the whole two-dimensional plane. These numbers are called the complex numbers. A complex number is written as a+ib, where a and b are real numbers. If you take the pair (a,b) to denote the coordinates of a point in the plane, then you can see how every complex number is linked to a point in the plane and vice versa. The i stands for $\sqrt{-1}$. But hang on a second — the square root of -1? You can't take square roots of negative numbers, can you?

Well with a bit of imagination you can! Which is why i is called an imaginary number! To find out more about the wonderful world of complex numbers, which are usually denoted by $\mathbb{C}$, read this article.

These are some of the groups of numbers that mathematicians have given names to. There are more, examples are transcendental numbers and numbers called quaternions. But the ones we have listed above are arguably the most important ones, so we will leave it here for today.