The Moon once churned an ocean of slushy magma

Over 50 years ago the rocks collected by Apollo 11 astronauts changed how we thought about the Moon. The same type of rocks, called anorthosites, that have formed through the crystallisation of magma, can be found on Earth. These lunar rocks suggested the theory, now widely accepted, that the Moon was formed in a collision between the proto-Earth and another proto-planet with the huge energy of this impact resulting in hot magma oceans on both the Earth and the Moon. The theory was that these lunar rocks were the result of crystals forming in the liquid magma and rapidly floating up to form the lunar crust between 4.3 and 4.5 billion years ago.

This theory has been largely accepted as the results of mathematical modelling of this process produced answers that agreed with the evidence from those first lunar rocks. Equations from fluid dynamics and thermodynamics model the mixing movement of the liquid magma through convection and the loss of heat through the surface of the Moon over time. When these models were run starting with possible initial conditions on the Moon after that impact with the proto-Earth, they predicted that crystals would develop in the magma as the temperature cooled. These crystals would either fall to the ocean floor or float to the surface to accumulate into the floating crust. The properties these models predicted for the rocks of the resulting lunar crust matched those brought back by the Apollo 11 mission.

New evidence needed a new approach

Since then meteorites from the Moon and samples from later lunar missions, as well as remote studies of the Moon's surface, have suggested that the rocks in the lunar crust are more varied, and have been produced over much longer time periods than can be explained using the early models of the liquid magma ocean. The models have been updated and advanced to try to account for this new evidence, but much of this later evidence remains unexplained.

Jerome Neufeld, from the University of Cambridge, and Chloé Michaut, of the Ecole normale supérieure de Lyon, have developed a new model of the formation of the Moon's crust. "Given the range of ages and compositions of the anorthosites on the Moon, and what we know about how crystals settle in solidifying magma, the lunar crust must have formed through some other mechanism," said Neufeld. Their model suggests that an ocean of hot slushy magma once existed on the Moon, finally explaining the diversity and range of ages of rocks from the lunar surface.

So Neufeld and Michaut came up with a different theory: rather than rocks crystallising in the liquid magma and immediately sinking to the ocean floor or rising to form a floating crust, the crystals would remain suspended in the magma ocean creating a slushy mix.

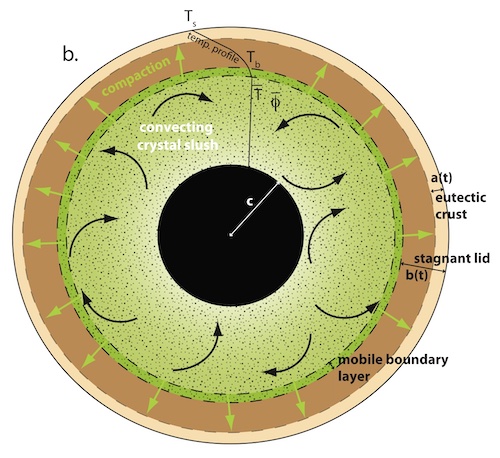

This is possible as it is difficult for the crystals to settle in the low lunar gravity, particularly when strongly stirred by the convecting magma ocean. If the crystals remain suspended as a crystal slurry, then when the crystal content of the slurry exceeds a critical threshold, the slurry jams and becomes very sluggish – the slushy magma has a higher viscosity. This occurs most dramatically near the surface, where the slushy magma ocean is cooled, resulting in a hot, well-mixed slushy interior and a slow-moving, crystal-rich lunar lid.

"We believe it's in this stagnant 'lid' that the lunar crust formed as lightweight, anorthite-enriched melt percolated up from the convecting crystalline slurry below," said Neufeld. "We suggest that cooling of the early magma ocean drove such vigorous convection that crystals remained suspended as a slurry, much like the crystals in a slushy machine."

A schematic model of the crust, the stagnant lid and the convecting slushy ocean. (Image from the paper: Formation of the lunar primary crust from a long-lived slushy magma ocean, published in Geophysical Research Letters (2022))

Neufeld and Michaut's mathematical modelling of this mechanism predicts four distinct stages in the evolution of the magma ocean on the Moon. As the ocean cools at the surface the fluid movement in the top layer reduces, producing the stagnant lid. Then crystallisation begins in the magma ocean and a crust forms on top of the stagnant lid while the temperature of the magma remains fairly constant. The magma then starts to cool, and more and more crystals form as the crust grows thicker. Finally, as the temperature continues to drop and more crystals form the magma becomes so viscous the convection currents stop and the ocean finally solidifies to form the Moon we see today.

These four stages occur for a wide range of the possible parameters describing the early state of the Moon. And the stages occur over several hundreds of millions of years, accounting for the greater age range of rocks that have been studied from the lunar crust.

This longer period of crystallisation also explains the diversity in the composition of rocks observed in the lunar crust. The composition of the rock crystallising out of the magma is affected by the composition of the liquid part of the magma, and in turn this crystallisation alters the composition of the remaining liquid part of the slush. As this crystallisation process occurs over a much longer time over the four stages of the model, the composition of the crystallised rock in the crust will also vary over this time period.

Fifty years after the mission that first placed humans on the Moon’s surface, the secrets of the Moon are still being revealed using the power of mathematical models.

This article is partly based on a news story on the University of Cambridge website. You can read more in the paper: Formation of the lunar primary crust from a long-lived slushy magma ocean, published in Geophysical Research Letters (2022)