Advent calendar door #6: Schrödinger's equation - what is it?

Here is a typical textbook question. Your car has run out of petrol. With how much force do you need to push it to accelerate it to a given speed? The answer comes from Newton's second law of motion:

$$F=ma,$$

where $a$ is acceleration, $F$ is force and $m$ is mass. This wonderfully straightforward, yet subtle law allows you to describe motion of all kinds and so it can, in theory at least, answer pretty much any question a physicist might want to ask about the world.

after Erwin Schrödinger, 1887-1961.

Or can it? When people first started considering the world at the smallest scales, for example electrons orbiting the nucleus of an atom, they realised that things get very weird indeed and that Newton's laws no longer apply. To describe this tiny world you need quantum mechanics, a theory developed at the beginning of the twentieth century. The core equation of this theory, the analogue of Newton's second law, is called Schrödinger's equation.

Waves and particles

"In classical mechanics we describe a state of a physical system using position and momentum," explains Nazim Bouatta, a theoretical physicist at the University of Cambridge. For example, if you've got a table full of moving billiard balls and you know the position and the momentum (that's the mass times the velocity) of each ball at some time $t$, then you know all there is to know about the system at that time $t$: where everything is, where everything is going and how fast. "The kind of question we then ask is: if we know the initial conditions of a system, that is, we know the system at time $t_0,$ what is the dynamical evolution of this system? And we use Newton's second law for that. In quantum mechanics we ask the same question, but the answer is tricky

because position and momentum are no longer the right variables to describe [the system]."

The problem is that the objects quantum mechanics tries to describe don't always behave like tiny little billiard balls. Sometimes it is better to think of them as waves. "Take the example of light. Newton, apart from his work on gravity, was also interested in optics," says Bouatta. "According to Newton, light was described by particles. But then, after the work of many scientists, including the theoretical understanding provided by James Clerk Maxwell, we discovered that light was described by waves."

But in 1905 Einstein realised that the wave picture wasn't entirely correct either. To explain the photoelectric effect (see the Plus article Light's identity crisis) you need to think of a beam of light as a stream of particles, which Einstein dubbed photons. The number of photons is proportional to the intensity of the light, and the energy E of each photon is proportional to its frequency f:

$$E=hf$$

Here $h=6.626068 \times 10^{-34} m^2kg/s$ is Planck's constant, an incredibly small number named after the physicist Max Planck who had already guessed this formula in 1900 in his work on black body radiation. "So we were facing the situation that sometimes the correct way of describing light was as waves and sometimes it was as particles," says Bouatta.

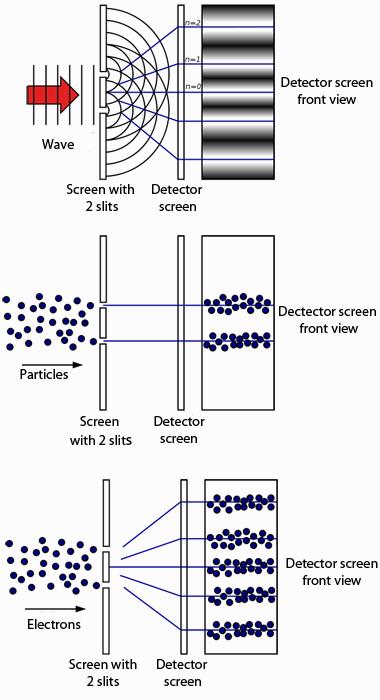

As we saw behind Door #5, Einstein's result linked in with the age-old endeavour, started in the 17th century by Christiaan Huygens and explored again in the 19th century by William Hamilton: to unify the physics of optics (which was all about waves) and mechanics (which was all about particles). Inspired by the schizophrenic behaviour of light the young French physicist Louis de Broglie took a dramatic step in this journey: he postulated that not only light, but also matter suffered from the so-called wave-particle duality. The tiny building blocks of matter, such as electrons, also behave like particles in some situations and like waves in others.

One of the most famous demonstrations of wave-particle duality is the double slit experiment we met behind Door #2. It's a very weird result indeed but one that has been replicated many times — we simply have to accept that this is the way the world works.

Schrödinger's equation

The radical new picture proposed by de Broglie required new physics. What does a wave associated to a particle look like mathematically?

In classical mechanics the evolution over time of a wave, for example a sound wave or a water wave, is described by something called a wave equation. It was the Austrian physicist Erwin Schrödinger in 1926 who came up with the analogous equation governing the evolution of our mysterious "matter waves", whatever they might be, over time. You can find out the details of how he got there in our article Schrödinger's equation – what is it? but here is what it looks like for a single particle

moving around in three dimensions:

$$\frac{ih}{2\pi } \frac{\partial \Psi}{\partial t} = -\frac{h^2}{8

\pi^2 m} \left(\frac{\partial^2 \Psi}{\partial x^2} + \frac{\partial^2

\Psi}{\partial y^2} + \frac{\partial^2

\Psi}{\partial z^2}\right) + V\Psi.$$

Here $V$ is the potential energy of the particle (a function of $x$, $y$, $z$ and $t$), $i=\sqrt{-1},$ $m$ is the mass of the particle and $h$ is Planck's constant. The solution to this equation is the wave function $\Psi(x,y,z,t).$

What does it mean?

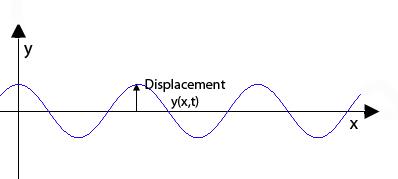

In classical mechanics a solution to the wave equation is a function giving you the shape, at any time $t$, of a wave, and there can be many solutions describing many possible waves.

But what does a solution of Shrödinger's equation mean? It doesn't give you a precise location for your particle at a given time $t$, so it doesn't give you the trajectory of a particle over time. Rather it's a function which, at a given time $t,$ gives you a value $\Psi(x,y,z,t)$ for all possible locations $(x,y,z)$. What does this value mean? In 1926 the physicist Max Born came up with a probabilistic interpretation.

This probabilistic picture links in with Heisenberg's uncertainty principle that we met behind Door #4 and it's one of the results that's often quoted to illustrate the weirdness of quantum mechanics. It means that in quantum mechanics we simply cannot talk about the location or the trajectory of a particle.

"If we believe in this uncertainty picture, then we have to accept a probabilistic account [of what is happening] because we don't have exact answers to questions like 'where is the electron at time $t_0$?',"

says Bouatta. In other words, all you can expect from the mathematical representation of a quantum state, from the wave function, is that it gives you a probability.

Whether or not the wave function has any physical interpretation was and still is a touchy question. "The question was, we have this wave function, but are we really thinking that there are waves propagating in space and time?" says Bouatta. "De Broglie, Schrödinger and Einstein were trying to provide a realistic account, that it's like a light wave, for example, propagating in a vacuum. But [the physicists], Wolfgang Pauli, Werner Heisenberg and Niels Bohr were against this realistic picture. For them the wave function was only a tool for computing probabilities."

You can find out more details in our article Schrödinger's equation – what is it? and the story will continue behind the next few doors!

Back to the Plus advent calendar 2025

About this article

Nazim Bouatta is a Postdoctoral Fellow in Foundations of Physics at the University of Cambridge.

Marianne Freiberger is Editor of Plus. She interviewed Bouatta in Cambridge in May 2012. She would also like to thank Jeremy Butterfield, a philosopher of physics at the University of Cambridge, and Tony Short, a Royal Society Research Fellow in Foundations of Quantum Physics at the University of Cambridge, for their help in writing these articles.