Playing billiards on doughnuts

Thanks to Corinna Ulcigrai of the University of Bristol for her help with this article.

Mathematicians love a game of billiards. Not because they like being in the pub (though many do), but because billiards is a great example of a chaotic dynamical system (see Chaos on the billiard table). In mathematical billiard the ball is assumed to have no mass, so it experiences no friction. Once you put it in motion, it will keep going, tracing out a trajectory on the table. We ignore those trajectories that hit one of the pockets, so we can assume that the ball is never swallowed up — it will keep going forever.

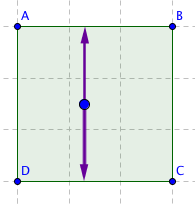

As you'll know from real billiards, it's hard to predict the trajectory of a ball beyond its first few bounces off the sides of the table. If you get the initial direction just right, it might fall into a regular pattern, such as bouncing back and forth between two opposite points on the table (see the figure on the right). But usually, the ball sets off on a long, complicated and jagged journey. How can you know which initial direction gives you which behaviour? And if the ball doesn't fall into a regular pattern, will it eventually visit every part of the table? Questions like these seem hard to answer, but mathematicians have developed a beautiful trick: turn the table into a surface on which the ball travels along straight lines without ever bouncing off anything. Then use the beautiful mathematics of surfaces to understand the trajectories. To see how it works, start by....

Reflecting the table, not the ball

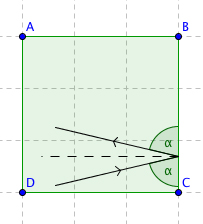

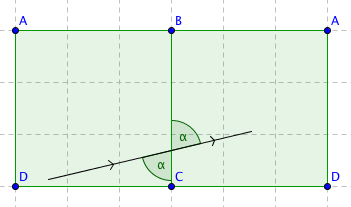

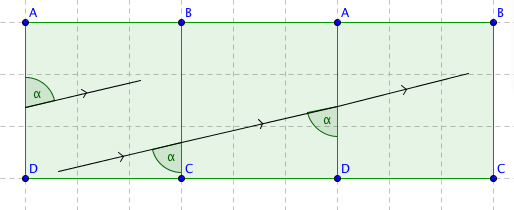

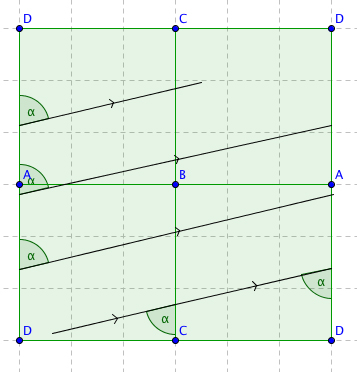

Let's start with a table that has the simplest possible shape, a square. Label its corners $A,$ $B,$ $C$ and $D$. Now imagine the ball starts somewhere near the bottom edge and heads off in a north-easterly direction, eventually hitting the right-hand edge of the square, its trajectory forming an angle $\alpha$ with the edge.

The right most square has its corners labelled in exactly the same way as the original, left-most square. So we can indicated the ball's trajectory in the original square and forget about the right-most one.

By inspecting what happens to a square when you repeatedly reflect it in its sides, you will see that you only need four copies of the square table to capture the trajectory of a ball — all other copies you produce will have their corners labelled in the same way as one of these four. So rather than continuing the trajectory on a new copy, you move onto one of the four squares you already have.

A torus with a trajectory marked. Image: Andrea Gambassi and Corinna Ulcigrai.

Round and round

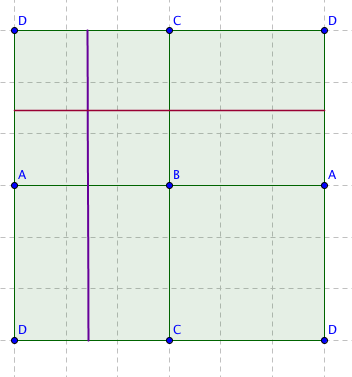

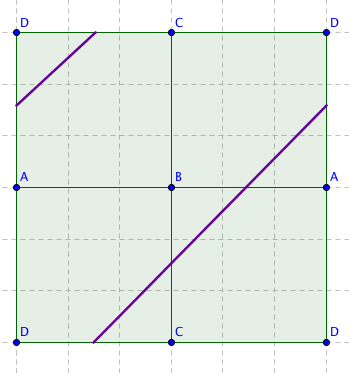

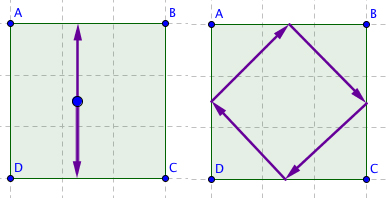

The way we have set things up means that any trajectory on the square table, no matter how complicated, turns into a collection of parallel lines on the square $S,$ whose ends join up when you glue the edges to form the torus. Curves on the torus that arise in this way have a special name. They are called geodesics — and mathematicians know a lot about them. (Technically, they are called flat geodesics as they are define by the "flat" metric the torus inherits from the square $S.$) One thing they know, which is easy to see, is that some geodesics are closed loops: they might wind around the torus a number of times but then return to where they started. An example is a geodesic that comes from a vertical or a horizontal line on $S.$ On the torus such a geodesic winds once around or through the hole.

The correspondence between periodic trajectories and rational numbers also tells us how likely we are to produce a periodic trajectory by shooting the ball in a random direction. Although there are infinitely many rational numbers and infinitely many irrational ones, the infinity of irrational numbers is "bigger" than the infinity of rational numbers (see Counting numbers). So much so that if you pick a number at random, your chance of picking a rational one is zero. Therefore, if you shoot a ball in a random direction, your chance of producing a periodic trajectory is zero too.

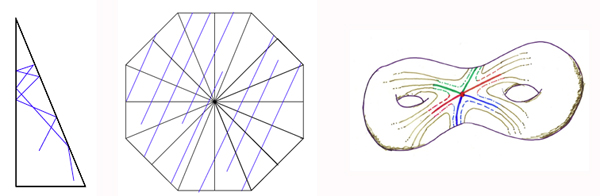

Different table, more holes

A square table is not the only one you can turn into a surface. The trick works whenever your table is a polygon (a shape whose sides are straight lines) whose corner angles are of the form $p/q \times \pi$ where $p$ and $q$ are whole numbers. Billiards played on a table with this shape is called rational polygonal billiards. For example, if your table is a triangle with corner angles $\pi/8,$ $\pi/2$ and $3\pi/8,$ then the reflection process will give you an octagon made up of 16 copies of the triangle, all meeting at the $\pi/8$ corner. When you glue opposite sides, you get a torus with two holes in it (see here to find out why). Whatever polygon you start with, as long as the angles have the correct form, you end up with a torus with some number of holes.

Image courtesy Corinna Ulcigrai.

Proving results about trajectories on these more complicated surfaces can be harder than for the simple torus, but luckily a whole box of mathematical tools has been developed to understand such surfaces. For example, a given surface can be deformed by shrinking and stretching. One thing you can do is deform a surface so that a long and complicated piece of geodesic is shrunk down to a manageable size. There are ways of doing this while at the same time keeping track of what happens to other features of the surface and its geodesics. What used to be a long and jagged piece of trajectory on the billiard table has now turned into a nice and short piece of geodesic on the surface.

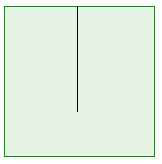

The dichotomy does not necessarily hold on a rectangular table with a barrier.

Using this beautiful trick you can then prove results about those long and jagged trajectories on the original table. For example, one natural question to ask is for what kind of table the dichotomy above holds: that a trajectory is either periodic or fills up the whole table in equal measure. Mathematicians have been able to prove that it holds when the table is a regular polygon and whenever the reflecting process gives rise to a regular polygon (a polygon whose sides all have the same lengths and whose internal angles are all equal), with the corresponding surface coming from gluing together opposite parallel edges. But there are also tables for which this isn't the case and the dichotomy doesn't hold. H. Masur and J. Smillie, relying on previous work by Veech, realised that this is the case on a rectangular table that has a barrier in it, as shown in the image. In this case trajectories that are not periodic do fill up the whole table, but they may spend more time in one part of the table than another. But the general question of which rational polygonal billiards satisfy the dichotomy and which don't is still wide open!

About this article

This article is based on an interview with Corinna Ulcigrai, a Reader in Pure Mathematics at the University of Bristol. Corinna was born in Trieste, Italy, in 1980. She obtained her diploma in Mathematics from the Scuola Normale Superiore in Pisa (2002) and defended her PhD in mathematics at Princeton University (2007), under the supervision of Ya. G. Sinai (Abel Prize Winner 2014). Her research is in the area of dynamical systems and ergodic theory. She is one of the few international experts in Teichmüller dynamics in the UK and has studied dynamical and chaotic properties of polygonal billiards and flows on surfaces. Corinna was awarded the European Mathematical Society prize for young mathematicians at the 2012 European Congress of Mathematics and was a recipient of the 2013 Whitehead Prize of the London Mathematical Society. She is married to a mathematician and has a young child.

Marianne Freiberger, Editor of Plus, interviewed Corinna at the British Mathematical Colloquium in London in April 2014.

Comments

Anonymous

How would things work out if we conceive of a 3-D billiards, theoretically speaking? I imagine it would be equivalent to a 4-D torus. Does the dichotomy extend to higher dimensions too?