Easy as pi?

Brief summary

This article explores the number $\pi$. We find out its definition, why its value can only ever be approximated, what it has to do with waves, and why it contains the history of the Universe.

The number $\pi$ is one of the most fundamental numbers in mathematics. It's what you get when you divide the circumference of a circle by its diameter. It doesn't matter how large or how small the circle is, whether you're on the Earth or on the Moon, its circumference is always equal to $\pi$ times its diameter. And its area is equal to $\pi$ times its radius squared.

Pinning down $\pi$

So what's the exact value of this beautiful beast? That's harder to say than you might think — $\pi$ is an irrational number. This means it can't be written as a fraction. Its decimal expansion is infinite and not periodic in any way.

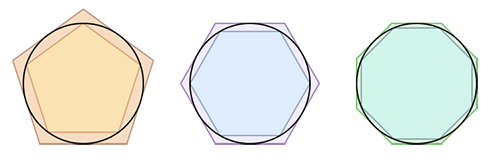

The Babylonians, the Egyptians, the Greeks, the Chinese, the Indians, the Arabs and even the old testament — all had stabs at pinning down $\pi$ (1 Kings 7:23 if you want to look up the bible reference). The main problem facing early geometers was that it's hard to measure a curvy shape. The first person to come up with a systematic approach to the challenge was Archimedes (famous for shouting "Eureka!" in the bath) in the third century BC. He sandwiched a circle between two regular polygons with 96 sides each, in a similar construction to those shown in this figure:

Archimedes thereby arrived at the estimate

$$223/71 < \pi < 22/7.$$

If you convert these fractions into decimals (and round a little) this gives

$$3.14 < \pi < 3.143,$$

so it only pins down the first three decimal digits of $\pi$.

It's clear that you can improve this estimate, making it as accurate as you like, by increasing the number of sides of the polygons involved. Archimedes was actually playing with the concept of a limit: the idea that a sequence of numbers (the perimeters of the polygons inscribed in the circle) can grow arbitrarily close to a bound (the circumference of the circle). The Greeks anticipated the invention of calculus by around a thousand years.

In turn, the age of calculus, with its penchant for infinite processes, gave $\pi$ its next major boost. During the 17th and 18th centuries mathematicians came up with ways of calculating $\pi$ that on the face of it have nothing to do with geometry. Instead, they involve infinite sums or products. A beautiful example comes from starting with 1, subtracting 1/3, then adding 1/5, subtracting 1/7, adding 1/9, and so on. As you keep going the result of your sum approaches $\pi/4:$

$$1-1/3+1/5-1/7+1/9- … = \pi/4.$$

This is a truly remarkable result. On the left of the equation you have nothing but arithmetic — the odd numbers, subtraction and addition — and on the right you have $\pi$ with its deep roots in geometry. The sum carries the name of Wilhelm von Leibniz, one of the inventors of calculus and the Scottish mathematician James Gregory, although it also seems to have been discovered two centuries earlier by the Indian mathematician Madhava of Sangamagrama.

Other, similarly surprising expressions for $\pi$ are displayed at the end of the article. Pretty as they are, most of them are still quite useless when it comes to calculating the digits of $\pi$, especially when you haven't got a calculator. If you add/subtract the first 100 terms in the Madhava-Gregory-Leibniz sum and multiply by 4, the number you get is accurate to only two decimal places, which is disappointing considering the effort involved.

By the middle of the twentieth century only just over 600 digits of $\pi$ were known, and known correctly, but all this changed with the advent of the computer. Various algorithms are in use to calculate ever more digits of $\pi$. As of July 2024, $\pi$ has been calculated to 202,112,290,000,000 (approximately 202 trillion) decimal digits.

The universe in a number

The first 50 decimal digits of $\pi$ are

$\pi = 3.14159 26535 89793 23846 26433 83279 50288 41971 69399 37510...$

As we said earlier, the digits don't repeat, in fact they look pretty random. Finding patterns in the decimal expansion of $\pi$ has been a favourite occupation of numerologists and mystics, but without success.

Mathematicians believe that the digits of $\pi$ really are in fact random, but what does that mean? One prerequisite for randomness is that each of the digits from 0 to 9 should appear in equal proportion (1/10th of the time), each pair of digits should appear in equal proportion (1/100th of the time), each triple should appear in equal proportion (1/1000th of the time), and so on. That's what you would expect to happen if you cast a fair ten-sided die with the digits written on the sides an infinite number of times. A sequence of numbers that has this property is called normal. Mathematicians believe that the sequence given by the decimal expansion of $\pi$ is normal, but they haven't been able to prove it yet.

Normality has a curious consequence: it means that every sequence of digits appears somewhere in the sequence. There are ways of translating text into numbers, so this means that every name of every person that has ever lived or will live, every text that has ever been written or will be written, appears somewhere in the expansion of $\pi$ (if it is indeed normal). The bible, the complete works of Shakespeare, the secret of the Universe (if there is one), and the future of humanity — it seems that they all appear somewhere in $\pi$. No wonder so many people are fascinated by this number.

The ultimate wave

For practical purposes we don't need to know many digits of $\pi$. Knowing it to 39 decimal places is enough to calculate the circumference of a circle the size of the known Universe with an error that's smaller than the size of a hydrogen atom. Engineers make do with far less accurate approximations of $\pi$. They have to, since no computer or measuring device can cope with its infinitely many digits.

The number $\pi$ appears in equations involving round objects, as you would expect. But it also appears in many others, particularly those describing waves: radio waves, sound waves, micro waves, water waves, light waves and all sorts of other oscillations that occur in nature and human made technology. It's an extraordinary stroke of mathematical luck that all wave forms, no matter how complicated, can be represented by a formalism that comes from walking round and round a circle.

To see how, place a circle in a standard Cartesian coordinate system centred on the point (0,0). To make things easy, take the radius of the circle to be 1. This means its circumference has length $2\pi$. Now start at the circle's right-most point (the point (1,0)) and walk around it in an anti-clockwise direction.

Watch what happens to the $y$-coordinate of the point (the up-down coordinate) as you do this. It starts at $0$ and then increases until the point has reached the top of the circle, after it has travelled a distance of $2\pi/4=\pi/2$. It then decreases until it reaches $0$ again when our point has reached the left-most point of the circle (the point (0,-1)). This happens after our point has travelled a distance of $\pi$ around the circle. As it keeps moving the $y$-coordinate deceases further until our point has reached the bottom of the circle (after travelling a distance of $3\pi/4$). After that, the $y$-coordinate increases again until it reaches $0$ when the point returns to its starting position, after having travelled around the full circumference of length $2\pi$.

All this happens in a perfectly symmetric manner so that when you plot the $y$-coordinate against distance travelled you get a perfectly regular wave.

You can see this in the Geogebra applet below. As you move the slider from left to right, the point $C$ moves around the circle. The point $G$ traces its $y$-coordinate, plotted against distance travelled.

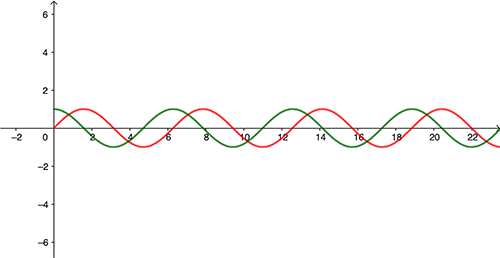

If our point traverses the circle a second time, so the distance walked increases from $2\pi$ to $4\pi$, the pattern repeats. The same happens if the distance increases from $4\pi$ to $6\pi$, then from $6\pi$ to $8\pi$, and so on. You end up with an infinitely long, perfectly regular wave. The $x$-coordinate gives a similarly perfect wave, offset against the first one by a distance of $\pi/2$ along the horizontal axis.

The two waves are, respectively, a sine wave and a cosine wave. If you have heard the terms sine and cosine before it was probably in your trigonometry lessons which were all about the relationship between the angles and the sides of triangles. But an angle is nothing but a turn through a fraction of a circle: a 180 degree angle corresponds to half of a circle, a right angle to a quarter of a circle, and so on. Elementary textbook definitions of sine and cosine only work for triangles that have one right angle. The waves we have found above are an extension of this traditional definition to include angles that are greater than 90 degrees.

Decoding messages

At first sight these waves appear too rigid to tell you much about the oscillations we encounter in real life. If you have a sound recorder that displays sound graphically and record yourself singing a single note, what you get will be a lot more jagged. That's because you're not just singing a pure tone, you are also singing lots of harmonics. Similarly, the radio waves sent out by GPS satellites to help you work out where you are don't arrive as clean waves either, they are likely to be corrupted by random interference from other waves.

But what makes sine and cosine waves so powerful is that any wave-like signal can be broken up into pure sine and cosine components. We know this because of a result published in 1822 by the French mathematician Jean Baptiste Fourier. Fourier is a great counterexample to the idea that people produce their best mathematics before they are 30. He started out training as a priest, then joined the French revolution, was incarcerated during the Terror but managed to avoid the guillotine, and later travelled to Egypt as scientific advisor to Napoleon's invasion. It was at the age of 55, when he was back in Paris at the Académie des Sciences, that he produced his seminal book Théorie analytique de la chaleur.

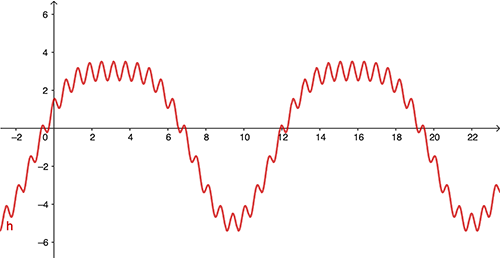

As the name suggests Fourier came across his result as he was trying to describe how heat flows through a metal plate and realised that it's easier to assume that the heat source behaves in a periodic fashion, just like a wave. Loosely speaking, his important result says that pretty much any periodic curve can be represented as a (possibly infinite) sum of sine and cosine waves; objects like

$$y = cos(x) + 4sin(0.5x) + 0.5cos(10x).$$

with $y$ plotted on a vertical axis against $x$ on the horizontal one.

The Scottish physicist Lord Kelvin hailed Fourier's book a "great mathematical poem" and the analogy fits this result — like composing a poem from words, you can compose complicated shapes from pure sine and cosine waves.

Fourier's result isn't much good to you if you don't know what the constituent components of a complicated waveform are, but remarkably mathematicians have developed a technique, called Fourier analysis, which helps you figure out just that. All types of signals can be decomposed in this way so Fourier analysis has a huge range of applications. It is used to analyse the radio signals from GPS satellites that tell you where you are. You can use it to understand the sound of a real instrument to synthesise it on a computer, or to clean up a digital sound recording. In medical science you can use it to reconstruct the insides of a person from a CAT scan and in image processing to compress digital images and eliminate defects. The list of applications is almost endless.

The number $\pi$ has taken us from pure geometry through calculus and randomness to a wealth of applications in science and engineering. It really is a remarkable number!

Other expressions for $\pi$

$$\pi/2 = \frac{(2 \times 2 \times 4 \times 4 \times 6 \times 6 \times …)}{(1 \times 3 \times 3 \times 5 \times 5 \times 7 \times …)}$$

$$\pi^2/6 = 1 + 1/2^2 + 1/3^2 + 1/4^2 + ….$$

$$\pi^3/32 = 1 - 1/3^3 + 1/5^3 - 1/7^3 + ….$$

$$\pi^4/90 = 1 + 1/2^4 + 1/3^4 + 1/4^4 + ….$$

About this article

Rachel Thomas and Marianne Freiberger are the editors of Plus. This article is based on a chapter of their book Numericon: A journey through the hidden lives of numbers.