Euler's polyhedron formula

This article is part of Five of Euler's best. Click here to read the other four problems featured in this series, which is based on a talk given by the mathematician Günter M. Ziegler at the European Congress of Mathematics 2016.

Think of a triangle. Now think of a square, followed by a pentagon, a hexagon, and so on. These shapes are called polygons. "Poly" is the Greek word for "many" and "gon" is the Greek word for "angle".

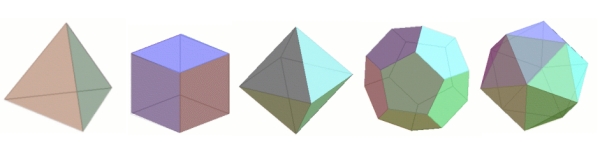

Now move up a dimension. Think of a cube, a pyramid, or perhaps an octahedron. These are all polyhedra ("hedra" is the Greek word for "base"). A polyhedron is an object made up of a number of flat polygonal faces. The sides of the faces are called edges and the corners of the polyhedron are called vertices.

The Platonic solids are examples of polyhedra. From left to right we have the tetrahedon with four faces, the cube with six faces, the octahedron with eight faces, the dodecahedron with twelve faces, and the icosahedron with twenty faces.

Now imagine counting the number V of vertices, the number E of edges and the number F of faces of a polyhedron. It turns out that, as long as your polyhedron is convex (has no sticky out bits) and has no holes running through it, the number of vertices minus the number of edges plus the number of faces,

V - E + F,

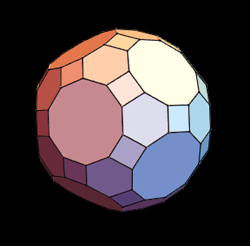

is always equal to 2. Your polyhedron could be a cube, an octahedron, something more intricate like the great rhombicosidodecahedron in the picture below, or even something much more irregular. That's a truly amazing result.

A great rhombicosidodecahedron. Image from the Wolfram Demonstrations Project, created by Russell Towle , reproduced under CC BY-SA 3.0.

The expression

V - E + F = 2

is known as Euler's polyhedron formula. Euler wasn't the first to discover the formula. That honour goes to the French mathematician René Descartes who already wrote about it around 1630. After his death in Sweden in 1650, Descartes' papers were taken to France, but the boat carrying them sunk in the river Seine. The papers remained at the bottom of the river for three days, but thankfully could be dried after they had been fished out. Another famous mathematician, Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz, copied Descartes' notes on the formula around 1675. Thereafter Descartes' manuscript disappeared completely and Leibniz' copy was lost until someone rediscovered it in a cupboard at the Royal Library of Hanover in 1860. Quite a dramatic history for a mathematical formula.

While Descartes may have discovered the formula first, it was Euler who had a crucial insight. When you are looking at the polyhedron formula, precise measurements don't matter: you don't need to know at what angle two faces of a polyhedron meet, or how long their sides are. The polyhedron formula belongs to the world of topology, just as the bridges of Königsberg problem does. It tells us something, not about individual objects with certain dimensions, but about the nature of space.

Proving the polyhedron formula isn't actually that hard. You can read a proof here on Plus, or find a total of twenty proofs on the Geometry Junkyard.

About this article

This article is part of Five of Euler's best. Click here to read the other four problems featured in this series, which is based on a talk given by the mathematician Günter M. Ziegler at the European Congress of Mathematics 2016.

Günter M. Ziegler is professor of Mathematics at Freie Universität Berlin, where he also directs the Mathematics Media Office of the German Mathematical Society DMV. His books include Proofs from THE BOOK (with Martin Aigner) and Do I count? Stories from Mathematics..

Marianne Freiberger is Editor of Plus. She really enjoyed Ziegler's talk about Euler at the European Congress of Mathematics in Berlin in July 2016, on which this article is based.

Comments

Guest

Great article, great pictures - thanks. I knew of Euler's formula but no the history of it.

I think there is a typo near the end of the article: "you don't need to know at what angle *to* faces of a polyhedron meet".

Marianne

Thanks for spotting that, we've corrected it.