Proof assistants (part 2)

Proof assistants: creating community

In the first part of this article, we explored what a proof assistant is and gave a link to a simple example. Of course, the hope with proof assistants is to be able to check proofs that are more complicated than the one in the previous section. In November 2023, a mathematical theorem called the Polynomial Freiman-Ruzsa conjecture (more in the last paragraph of this Wikipedia entry) was proven. This result from combinatorics turned out to be some titanic task to prove, and the proof was achieved by an impressive group: Timothy Gowers, Ben Green, Freddie Manners and Terence Tao.

The conjecture was proven in a 33-page, mostly self-contained paper (that is, there wasn’t too much reliance on results proven in other papers.) In particular, it seemed like the sort of paper that would be perfect to try and put through a proof assistant such as Lean. As such, a group of approximately thirty people, led by Terence Tao, put their heads together to formalise the proof.

What is of note is that although this is a result in combinatorics, not all of the contributors were combinatorists. They were not all even mathematicians; some were computer scientists, and some were even just people who enjoyed solving puzzles. In the beginning stages of the formalising of a proof, a sort of skeleton of the proof is created, such that one can see that the puzzle is broken down into many pieces. It is called a dependency graph.

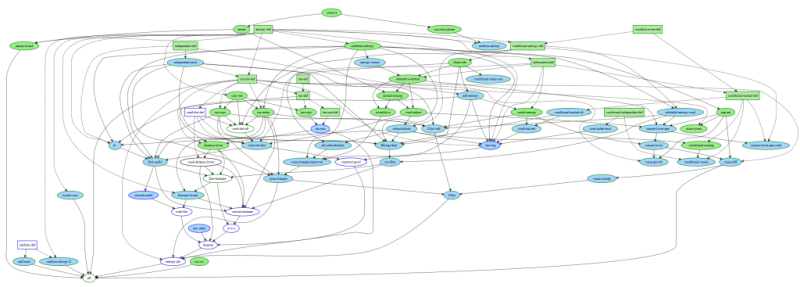

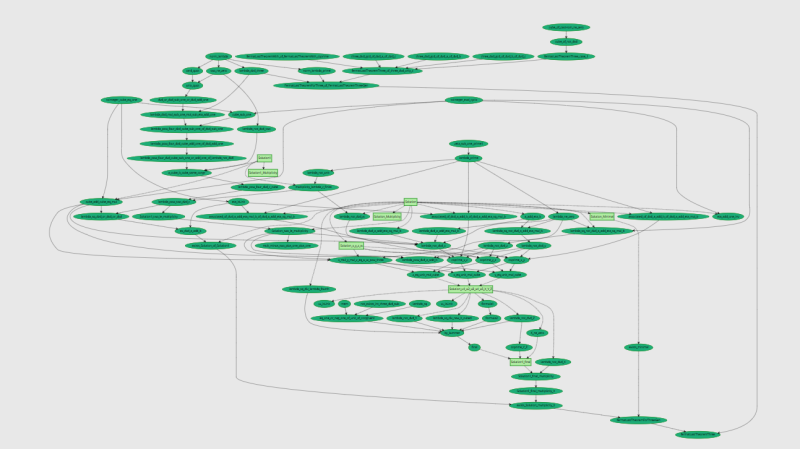

Here is an example of the graph for the Polynomial Freiman-Ruzsa conjecture, mid-way through proof formalisation. Each bubble either represents a definition (rectangle) or a theorem/lemma (ellipse). You can see that there are arrows which point from shape to shape. An arrow points from a theorem/definition to wherever it is needed for another theorem/definition. Slowly over time, the contributions of everyone involved turn the graph increasingly green (meaning that the particular definition or lemma has been coded up and checked). The graph even provides a final dopamine hit by turning the entire graph a satisfying dark green once the entirety of the theorem has been formalised. For the Polynomial Freiman-Ruzsa conjecture, this took around 3 weeks. You can easily analogise this to our tree metaphor from before. We want to adjoin the ultimate twig (the Polynomial Freiman-Ruzsa conjecture), but have to go down several branches that are shown by the arrows.

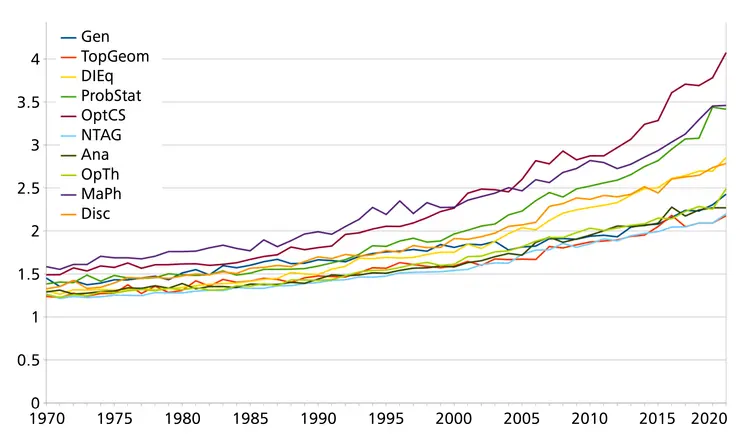

Mathematics has a (somewhat historically merited) reputation of being solitary in nature. Below is a graph of the average number of authors for a paper in clusters of ten mathematical areas.

There is certainly growth in the number of mathematicians who contribute on any given paper. But still, there being twenty or so people contributing on a mathematical project is a rarity.

A benefit of this, beyond the fun of contributing with several other people, is that for larger, perhaps trickier proofs, it allows a range of people to engage with the elements of the proof formalisation that best appeal to their personal interests and specialities.

Fermat's Last Theorem

Take, for example, Fermat’s last theorem, which was famously (correctly) proven in 1994 by Andrew Wiles with the help of Richard Taylor. In 2024, the EPSRC (Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, a British research council) provided a five-year grant to Kevin Buzzard in order that it could be formalised on Lean.

His aim was originally to reduce Fermat’s Last Theorem to results which were known in the 1980s. Wiles’ proof is very intricate and requires work with several areas of mathematics: group theory, commutative algebra, real analysis, complex analysis, algebraic geometry, differential geometry etc. Buzzard self-admittedly isn’t the largest fan of real analysis. “If I do this until I die, I’ll be doing real analysis at the end.” However, now that the project is growing in numbers, it means that collaborators who perhaps favour one area of the proof more (such as maybe real analysis) can just crack on with that. Nobody has to know how the entire proof works.

Machine Lean-ing

One way in which formal proof assistants could become incredibly useful is if we were able to use them in tandem with large language models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT, DeepSeek, Gemini or Llama. These AI models are certainly becoming quite good at mathematics. Recently (2025), an LLM performed at gold medal standard in the International Mathematics Olympiad.

However, they are not perfect, and certainly, one of the big problems currently is hallucinations, that is, LLMs making mistakes. Kevin Buzzard explains “The big question is, how are they going to get better?...Currently, people believe two different routes, right? Some people are saying we should just keep doing what we're doing. Make them hallucinate less, give them more data, and eventually they'll just read all the papers in this office and eventually they'll be brilliant. But then my suggestion is actually, no. We should teach them formal languages and stop them hallucinating that way. So, who knows which way will win...I'm betting on the formal language side of things.”

An issue with LLMs at the moment is that their instinct when they are stuck isn’t to give up as humans do, but rather to lie or smudge a proof. One way to circumnavigate this is to require LLMs to produce Lean code. That is, rather than produce proofs for human consumption, they would first have to write the proof in Lean. The Lean Code could then run, and it would tell the LLMs where the proof is incorrect or if there is a gap in it. The LLMs would then have to check its mistakes rather than get away with a smudge, which might bypass an untrained eye.

At this point, of course, they could translate back the Lean code into naturalistic language. For LLMs to begin to be able to do research-level mathematics (if they are even able to do that), they can’t be allowed to get away with smudging mistakes. Hence, having to operate via Lean would be a great way of doing this.

Of course, to be able to do this, they would first need to be trained on a large amount of Lean code. Fortunately, large projects such as Fermat’s Last Theorem and Polynomial Freiman-Ruzsa will produce just that.

Big Proof at the Isaac Newton Institute

Proof formalisation is an active area in mathematics that attracts some of the greatest minds in the field. Instrumental in establishing the area was a 2017 research programme run by the Isaac Newton Institute for Mathematical Sciences in Cambridge (INI) called Big Proof. At the first Big Proof conference in 2017, most of the room were not mathematicians, but rather computer scientists. The INI were very much ahead of their time when it came to seeing the importance of proof assistants in the future of mathematics.

However, despite the perhaps low attendance of mathematicians, it was still influential. Indeed, Kevin Buzzard describes being inspired to take on his current research by a talk by Tom Hales at the original event: “I watched the first talk by Tom Hales, and he was using the same tools as me but he was talking about the idea, about using them to do modern research…I'd just spent two weeks proving the square root of two was irrational, and I'm looking at these slides, thinking, ‘Wouldn't it be great to do advanced algebraic geometry in this system?’ ”

Skipping a few years forward to 2025, the most recent Big Proof took place. This time, many mathematicians are right at the forefront of their respective fields (three Fields Medalists notwithstanding). The dream of formalising mathematics is very much alive. According to Buzzard, there are only two small parts of his original undergraduate degree not currently coded in Lean, and the field is only growing!

Thoughts for the future

One doesn’t want to use too broad a brush in thinking about what the future of mathematics is with proof assistants. However, if one is allowed to be optimistic…with additional LLM assistance in the future, it might be possible that formal proof assistants might catch up with modern mathematics. David Hilbert dreamt of formalising all of mathematics and with proof assistants, this dream might just come true. Furthermore, who knows whether there is a missing branch in our mathematics tree that we might uncover? And, who knows what AI might be able to do with the all the capabilities of Lean under its belt?

About the Author:

Ben Watkins finished his 4th year of mathematics at Cambridge in 2025. His interests include theoretical physics, quantum computation, and mathematical communication: sharing the joy of maths with a wider audience!

This content forms part of our collaboration with the Isaac Newton Institute for Mathematical Sciences (INI) – you can find all the content from the collaboration here.

The INI is an international research centre and our neighbour here on the University of Cambridge's maths campus. It attracts leading mathematical scientists from all over the world, and is open to all. Visit www.newton.ac.uk to find out more.