Proof assistants

What is a proof?

Mathematics is a game played according to certain simple rules with meaningless marks on paper – David Hilbert, being more than a little bleak.

Mathematics is different from the sciences. Whilst there is a great interplay between the two, (some see mathematics as the language of science), they are two entirely different games. Science is fundamentally a game of observations and empiricism; something is factual in the sciences only if it is manifest to the world and the Universe that we observe. Maths, however, is a game of axioms.

Axioms can be thought of as the rules of mathematics. They are things that can’t be derived or proven from which we build up everything else. An example of a collection of axioms would be the Peano axioms, which are the axioms of the natural numbers. They include things such as “0 is a natural number” or “if x=y, then y=x”. They can be, in some sense, "obvious" statements or "simple rules" to use Hilbert’s language. To say something is true in mathematics, such as “there are infinitely many prime numbers”, is to say that we can prove that this statement can be reduced to the axioms. All the beauty of mathematics, all the intricate structures and formidable theorems (or "meaningless marks on paper" to some), are in some sense lucky churnings out from axioms.

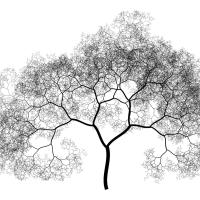

This having been said, this isn’t the experience of doing maths. Almost all pure maths papers will make no mention of axioms. Rather, the experience is mostly of proving theorems by showing that they are reducible to other statements that have been previously proven. The image to have in mind is of a large tree. From the trunk of axioms sprout big branches of primordial theorems, then smaller branches sprout from the bigger branches, and twigs sprout from those smaller branches. Ultimately, one can trace the twig back to the trunk, but ultimately it is more useful to think of it as attached to its branch. (This metaphor does wear thin remarkably quickly when one considers that some theorems can be proven in several ways, and that some theorems can be true without there being a proof.)

It is essential however, to check that the proofs that are written in papers are correct and complete.

An example: the four colour theorem

The four-colour theorem says that any map where there are boundaries (e.g. a map of the United States) can be coloured using 4 different colours such that no two regions that share a boundary are the same colour. You can have a play with this here.

You can colour in a million maps, but this wouldn’t amount to a proof. What if there’s a counterexample that you haven’t spotted? In 1879, Alfred Kempe seemed to think that he had shown there was no counterexample and released a "proof" of the theorem. It wasn’t until 11 years later that Percy John Heawood showed that this proof was, in fact, false. There was an assumption used in Kempe’s proof that was incorrect.

This leaves a perfectly valid question. When a proof is published, how can we be sure that it is correct? How can we be sure that it is a twig on the tree, and not just some twig destined to spend its lonely days on the floor? There must be some way of checking that these proofs are correct, right?

Peer reviewing is the way that this is usually done. That is, when a paper is published, a small group of other mathematicians will check your work. However, what if these peers miss your mistake? Furthermore, nowadays, it isn’t uncommon for papers to be regularly released which are several hundred pages long. There simply isn’t the peoplepower to check these papers.

This is a motivation for having proof assistants. These are software tools, produced by computer scientists, which verify with certainty whether a proof is correct by requiring every step to be formally stated. Otherwise the tools will consider the proof incomplete.

Kevin Buzzard is a Professor of Pure Mathematics at Imperial College London. We met Buzzard after he participated in the Isaac Newton Institute’s Big Proof programme (more on that later in the article!) He explains “Well, the thing is, if you're playing chess against a chess computer, then you can't make an illegal move, right? It's pretty easy in chess to detect that your opponent has made an illegal move, but the problem is in maths. Maths is much more complicated than chess. We get papers published that have mistakes in, it is rare, and the mistakes are often not important, but sometimes there's a big howler. And, the thing about doing maths in a proof assistant is that it sort of removes that possibility of making an error…the system does work without them, but it's just that, it's 2025 and now we can have that little extra. If we want it, we can have that extra edge. ”

For example, the first correct proof of the four-colour theorem was given in 1976 by Kenneth Appel and Wolfgang Haken. This was done by reducing the number of possible counterexamples that had to be checked from infinity (quite a large number) to 1,834 (a large, but much smaller number). They then checked that these weren’t counterexamples using a computer. The full proof was published and contained a microfiche supplement of over 400 pages. This would be too long for any (sane) human to go through and check.

However, in 2005, a fully formalised proof was given by Benjamin Werner and Georges Gonthier in the proof assistant Rocq (formerly called Coq.)

What exactly is a proof assistant?

Kevin Buzzard describes a proof assistant as a particularly pedantic student. Imagine being at the front of a room giving a lecture where you are proving some result. Whenever you make any step in your proof, be it as obvious as adding 1 to both sides of the equation, some particularly irksome undergraduate at the front of the room raises their hand and says "why is that true?"

When you use a proof assistant, you will write some code, and the code can only run if there are no assumptions at any point that you haven’t clarified. Suppose, whilst doing a proof, you need to make use of some theorem, and this theorem has three prerequisites. That is, it says that if you know three properties about a particular object (e.g. it is a natural number, it is larger than 3, it is a prime number), then you know some fact about it (e.g. its square is one larger than a multiple of 24). Then, when you make use of that theorem (e.g on a number such as 43), the code can’t run unless you show it that all the prerequisites are true, (e.g. that it is a natural number, that it is larger than 3 and that it is a prime number).

This sort of pedantry isn’t typical when doing maths, but it allows us to rest assured that a proof is, for definite, correct when the code runs. You can see how this works in practice here. To find out about more sophisticated theorems that have been proved using proof assistants, and how proof assistants have changed the way people do mathematics, see the second part of this article.

About the Author:

Ben Watkins finished his 4th year of mathematics at Cambridge in 2025. His interests include theoretical physics, quantum computation, and mathematical communication: sharing the joy of maths with a wider audience!

This content forms part of our collaboration with the Isaac Newton Institute for Mathematical Sciences (INI) – you can find all the content from the collaboration here.

The INI is an international research centre and our neighbour here on the University of Cambridge's maths campus. It attracts leading mathematical scientists from all over the world, and is open to all. Visit www.newton.ac.uk to find out more.