Co-production of mathematical models

Brief summary

This article looks at a pioneering new research project which aims to produce mathematical models together with the people who are affected.

We may not notice it, but mathematics impacts our lives on a daily basis. Mathematical models inform policy decisions around the economy and public health. They are used to understand climate change and how to respond to it. They are vital in the design of public buildings and spaces. They are even used to try and prevent crime.

These few examples (and there are more) all have one thing in common. Not only do the areas involved impact us, our behaviour also shapes them. The spread of diseases, the economy, the climate, our public spaces, are all affected by what we do.

It seems reasonable, then, that the mathematical models should reflect people's interaction with each other and their environment, and that they should take account of people's perspectives and priorities. But mathematics isn't traditionally viewed as being great at capturing human behaviour. What is more, to capture people's behaviour you need to understand it first — and that's difficult.

The idea of co-production of mathematical models is to meet the challenge by getting members of the public to help build the mathematical models from the start. "Co-production is [probably the most intensive] type of public participation in research," says Liz Fearon, an epidemiologist at University College London who is currently setting up a pioneering co-production project. "Members of the public, who are part of the affected population of the research, are involved from the beginning in the development of research and research priorities, and throughout the whole project. As equal, and equally valued, members of the team."

The approach goes beyond types of public participation that have been happening for a while, for example in the medical sciences, where members of the public are brought in at certain stages of a research project, for example through focus groups or surveys. In co-production they are immersed in a project for the duration and help to direct it.

Behaviour is key

Epidemiology, Fearon's field of expertise, is a prime example of an area where public participation can be game-changing. During the COVID-19 pandemic Fearon worked on test, trace, and isolate (TTI). The idea was that to reduce transmission, people should be enabled to test for COVID-19, isolate if positive, and that their contacts should then be traced and asked to isolate as well.

You can listen to Liz Fearon talk about co-production in our podcast.

Mathematical modelling was used from early on in the pandemic to understand the potential of TTI to stem the spread, on its own or alongside other interventions. Models are useful because they can simulate how a disease might spread through the population under a given set of assumptions and circumstances — with an intervention in place, without the intervention in place, with a particular type of the intervention in place, etc. You can then compare the various outputs and adopt the strategy that appears most useful. (See here for a quick introduction to one of the most basic epidemiological models and here for a look at a more complicated model used for COVID-19.)

However, as we also saw during COVID-19, a particular intervention being officially "in place" doesn't mean that everyone will stick to it. People may not be able to get hold of a test, they may not be able to isolate because they need to go to work to earn money, or they may simply not want to adhere.

"A key thing that became clear to us early on was that to model anything to do with interventions, you need to make assumptions about what proportion of the population is able and willing to take them up," says Fearon. "It worried me that, if we made unrealistic assumptions, [the modelling might suggest] that policy A was better than policy B, when in practice policy B was better than policy A."

Fearon and her colleagues did work with behavioural scientists and tried to take account of empirical evidence about people's likely behaviour, for example from surveys. "But to be honest, in practice it was really challenging to incorporate this information into the modelling we were producing for the scientific advisory channel process — because we were [often] asked to do that over very short time scales."

Modelling is subtle

Even when there's time to take account of empirical research into people's behaviour, without feedback from affected people, your model may end up too inaccurate to be of use. Mathematical models can only ever provide a simplified description of reality and choices need to be made by the modeller on what bits to simplify and how.

"In the development of models there are what might seem like small decisions being made all the time," says Fearon. "We might see them as technical decisions but they often have bearing on how we are representing the transmission process and how people interact with interventions."

As an example Fearon mentions previous work on modelling transmission of sexually transmitted infections, where assumptions need to be made about the rate at which people form relationships and the rate at which they have sex within a relationship. "It's very difficult for an individual modeller, or even a modelling team, to make all those decisions without any kind of feedback from the population who is being modelled or from other disciplinary perspectives — it is difficult to even recognise sometimes what is an assumption and what is a technical decision."

Benefits can come with harms

Another thing that became abundantly clear during the COVID-19 pandemic is that driving down transmission comes at a price. The primary aim of interventions is to stop a disease from spreading. "But we are also balancing [this aim] against potential harms a public health intervention might have." We're all too familiar with the harms of the COVID-19 restrictions during the pandemic, on us as individuals and on society as a whole. But more subtle interventions can also come with unintended consequences. Public health messages can provoke stigma or fear, for example, which is hard to gauge and can be extremely damaging.

"For most public health interventions there is some kind of balance [to be struck] between harms and transmission aims," says Fearon. "We really want broader public input into what those harms are that are experienced by the public. Because we as modellers or public health practitioners might not understand what they are, [or] how they are balanced against the epidemiological aims."

Co-producing a model for mpox

Fearon's current project, inspired in part by her pandemic experience, is called Co-produced mathematical modelling of epidemics together (COMMET). "Our aim is to develop methods, guidance and tools to enable co-production in epidemic response modelling," says Fearon. COMMET is an interdisciplinary project that will involve, not just mathematical modellers, but also experts in social science, human centred design, and linguistics.

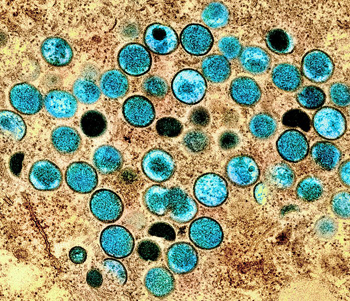

A key component of COMMET is a demonstration project centred around mpox, an infectious disease related to smallpox which can be severe or even fatal. Anyone can get mpox, but it doesn't spread as easily as COVID-19. Transmission happens mostly through close physical contact.

In 2022 an outbreak of mpox appeared suddenly and spread rapidly through Europe, the Americas and then the rest of the world. The outbreak outside of Africa, which still continues, has mainly affected men who have sex with men (the gay, bisexual and MSM community) via sexual transmission.

Fearon is currently pulling together the team of people who will be part of the mpox project. "We have just recruited three co-producers, people with lived experience relevant to mpox, who will be working as part of our main research team, coming to our meetings, reviewing our documents, and taking part in research activities. We are also going to recruit a peer researcher, someone who has both research experience and lived experience relevant to [mpox in the UK context]. Working with community organisations we will also hold workshops with members of the public to get a broader range of input beyond our three co-producers."

Interestingly, COMMET will also turn the spotlight on the people who do the modelling: a team of ethnographers will shadow modellers, observing what they do and how they do it. "Additionally we will reflect on ourselves as a team to evaluate how co-production has worked for us." The idea is to understand how the modellers' cultural landscape may shape their perspective on a disease and people's behaviour. "This is to recognise that every discipline has a set of norms, processes and methods that have been developed over time and exist within a particular social and economic universe," says Fearon. "All of these things have bearing on the science that comes out."

A blatant example of this comes from medicine, where research has traditionally been done mostly with white men in mind. Women and people from other ethnicities have often been ignored. When it comes to modelling, Fearon hopes that co-production and self-reflection on the part of the modellers will not only produce better models, but also address the inequalities that epidemics tend to amplify — as we saw with COVID-19 when disadvantaged groups were hit harder by the disease itself as well as the harms of interventions. To this end Fearon and her colleagues are also seeking to involve people from under-represented groups in their project.

Communication is key

The aim, ultimately, is to build a model that can help us understand the spread of mpox in the UK and the effect of interventions, which truly reflects the behaviour and concerns of the people affected.

For this to work, the communication between co-producers and modellers needs to go in both directions. "Some of our work will overlap with work in maths communication, seeing it as a two-way process where mathematicians are trying to integrate information [from co-producers], but also explaining the mathematical side enough to enable people who don't have the maths background to engage and critique," says Fearon.

This may seem like a tall order — for many people maths ranks top as the most impenetrable subject ever. But while the language in which models are written is inaccessible to all but experts, the conceptual make-up of a model can often be explained (see for example our communication work with members of the JUNIPER partnership of disease modellers, of which Fearon is a member). What will be new is that non-experts will not just passively learn about models, but actively help shape them. It's a pioneering idea that casts a new light on mathematics and its role and standing in society.

Once the mpox project is complete, Fearon and her colleagues will reflect on the co-production approach and work through their wider networks to test it out with other infections. We will be sure to meet with her throughout the COMMET project to report on how it's going. If the project is successful then perhaps other disciplines that make use of mathematical models will follow suit. To paraphrase the mathematician Hannah Fry, it's about doing mathematics with the people who are affected by it, not to them.

About this article

Liz Fearon is an Associate Professor of Infectious Disease Epidemiology at University College London. She is interested in understanding social influences on infectious disease transmission in order to support health equity, particularly in relation to HIV, sexually transmitted infections and epidemic response.

We saw Fearon talk about the COMMET project at the 2025 Annual Meeting of the JUNIPER partnership of disease modellers, which took place in March 2025 at the University of Lancaster. Marianne Freiberger, Editor of Plus, interviewed Fearon in April 2025.

You can listen to Fearon talk about co-production in our podcast and you can watch her give a talk about the subject at a mathematics communication conference we organised in November 2024 as part of our Mathsci-comm network.

This article is part of our collaboration with JUNIPER, the Joint UNIversities Pandemic and Epidemiological Research network. JUNIPER is a collaborative network of researchers from across the UK who work at the interface between mathematical modelling, infectious disease control and public health policy. You can see more content produced with JUNIPER here.