Does infinity exist?

In the latest poll of our Science fiction, science fact project you told us that you wanted to know if infinity exists. Here is an answer, based on an interview with the cosmologist John D. Barrow. Click here to see other articles on infinity and here to listen to our interview with Barrow as a podcast.

Does infinity exist?

Does infinity exist?

This is a surprisingly ancient question. It was Aristotle who first introduced a clear distinction to help make sense of it. He distinguished between two varieties of infinity. One of them he called a potential infinity: this is the type of infinity that characterises an unending Universe or an unending list, for example the natural numbers 1,2,3,4,5,..., which go on forever. These are lists or expanses that have no end or boundary: you can never reach the end of all numbers by listing them, or the end of an unending universe by travelling in a spaceship. Aristotle was quite happy about these potential infinities, he recognised that they existed and they didn't create any great scandal in his way of thinking about the Universe.

Aristotle distinguished potential infinities from what he called actual infinities. These would be something you could measure, something local, for example the density of a solid, or the brightness of a light, or the temperature of an object, becoming infinite at a particular place or time. You would be able to encounter this infinity locally in the Universe. Aristotle banned actual infinities: he said they couldn't exist. This was bound up with his other belief, that there couldn't be a perfect vacuum in nature. If there could, he believed you would be able to push and accelerate an object to infinite speed because it would encounter no resistance.

For several thousands of years Aristotle's philosophy underpinned Western and Christian dogma and belief about the nature of the Universe. People continued to believe that actual infinities could not exist, in fact the only actual infinity that was supposed to exist was the divine.

Mathematical infinities

But in the world of mathematics things changed towards the end of the 19th century when the mathematician Georg Cantor developed a more subtle way of defining mathematical infinities. Cantor recognised that there was a smallest type of infinity: the unending list of natural numbers 1,2,3,4,5, ... . He called this a countable infinity. Any other infinity that could be counted by putting its members in one-to-one correspondence with the natural numbers was also called a countable infinity.

The even numbers are in one-to-one correspondence with the natural numbers.

The even numbers are in one-to-one correspondence with the natural numbers.

This idea had some funny consequences. For example, the list of all even numbers is also a countable infinity. Intuitively you might think there are only half as many even numbers as natural numbers because that would be true for a finite list. But when the list becomes unending that is no longer true. You can draw a line from 1 to 2 and from 2 to 4 and from 3 to 6 and so on forever in the two lists. Every even number will be joined to one and only one number in the list of natural numbers, so there are as many numbers in the one list as there are in the other. This fact was first noticed by Galileo (although he counted the squares 1, 4, 9, 16, ..., rather than the even numbers) who thought it was so strange that it put him off thinking about infinite collections of things any further. He thought there was just something dangerously paradoxical about them. For Cantor, though, this feature of being able to create a one-to-one correspondence between a set of numbers and a subset of them was the defining characteristic of an infinite set.

Similarly, the list of all the rational numbers, that is all the fractions, is a countable infinity. The way to count those systematically is to add the numerator and the denominator, and then first write down all the fractions for which this sum is 2 (there is only one, 1/1), then all the ones for which it is 3 (1/2 and 2/1), and so on. Each time you are counting only a finite number of fractions (the number of fractions p/q where p+q=n is n-1). This is an infallible recipe for counting all the rational numbers: you won't miss any. This shows that the rational numbers are countable too, even though in an intuitive sense there seem to be lots more of them than there are natural numbers.

Cantor then went on to show that there are also other types of infinity that are in some sense infinitely larger because they cannot be counted in this way. One such infinity is characterised by the list of all real numbers. These cannot be counted; there is no recipe for listing them systematically. This uncountable infinity is also called the continuum.

But finding this infinitely bigger set of the real numbers wasn't the end of the story. Cantor showed that you could find infinitely bigger sets still, all the way upwards forever: there was no biggest possible infinite collection of things. If someone presented you with an infinite set A, you could create a bigger one that wasn't in one-to-one correspondence with A just by finding the collection of all the possible subsets of A. This never-ending tower of infinities pointed towards something called absolute infinity — an unreachable summit of the tower of infinities. (You can find out more about Cantor's work in the Plus article A glimpse of Cantor's paradise.)

Mathematically, Cantor treated infinities not just as potential, but as actual. You could add them together — a countable infinity plus another countable infinity is a countable infinity — and so on. There was a great fuss in mathematics about whether this should be allowed. Some mathematicians thought that by allowing Cantor's transfinite quantities, as they were called, into mathematics, you were introducing some type of subtle contradiction somewhere. And if you introduce contradictions into a logical system, then eventually you will be able to prove that anything is true, so it would bring about the collapse of the whole system of mathematics.

This worry has led to the definition of finitist or constructivist mathematics, which only allows mathematical objects that you can construct by a finite sequence of logical arguments. Your mathematics then becomes a bit like what your computer can do. You set down certain axioms and only things that can be deduced from them by a finite sequence of logical steps are considered true. This means that you're not allowed to use proof by contradiction (or the law of the excluded middle) as an axiom, proposing that something does not exist and then deriving a contradiction from that proposition to conclude that it must exist. Nineteenth century proponents of this constructivist view were the Dutch mathematician LEJ Brouwer and Leopold Kroneker and in the twentieth century Hermann Weyl was interested in it for a period. There are still some mathematicians who want to define mathematics in this way for philosophical reasons and others who are just interested in what you can prove if you do define it in this restricted way. (To find out more about this, read the Plus article Constructive maths.)

But generally Cantor's ideas have been accepted and today they form their own sub-branch of pure mathematics. This has led some philosophers, and even some theologians, to rethink their ancient attitudes to infinities. Because there are quite different varieties of infinity, it is clear that you don't have to regard the appearance of mathematical infinity as some sort of challenge to the divine as the medieval theologians believed. Cantor's ideas were at first actually taken up more enthusiastically by contemporay theologians than by mathematicians.

Scientists also started to distinguish between mathematical and physical infinities. In mathematics, if you say something "exists", what you mean is that it doesn't introduce a logical contradiction given a particular set of rules. But it doesn't mean that you can have one sitting on your desk or that there's one running around somewhere. Unicorns are not a logical impossibility but that doesn't mean that one exists biologically. When mathematicians demonstrated that non-Euclidean geometries can exist, they showed that there's an axiomatic system which permits them that is not self-contradictory. (You can find out more about non-Euclidean geometries in the article Strange geometries.)

Physical infinities

So infinities in modern physics have become separate from the study of infinities in mathematics. One area in physics where infinities are sometimes predicted to arise is aerodynamics or fluid mechanics. For example, you might have a wave becoming very, very steep and non-linear and then forming a shock. In the equations that describe the shock wave formation some quantities may become infinite. But when this happens you usually assume that it's just a failure of your model. You might have neglected to take account of friction or viscosity and once you include that into your equations the velocity gradient becomes finite — it might still be very steep, but the viscosity smoothes over the infinity in reality. In most areas of science, if you see an infinity, you assume that it's down to an inaccuracy or incompleteness of your model.

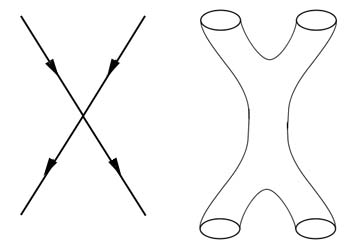

Two particles meeting form a sharp corner (left) but two loops coming together are like two pairs of trousers sown together. (The trouser diagram has time going downwards and space horizontal.)

In particle physics there has been a much longer-standing and more subtle problem. Quantum electrodynamics is the best theory in the whole of science, its predictions are more accurate than anything else that we know about the Universe. Yet extracting those predictions presented an awkward problem: when you did a calculation to see what you should observe in an experiment you always seemed to get an infinite answer with an extra finite bit added on. If you then subtracted off the infinity, the finite part that you were left with was the prediction you expected to see in the lab. And this always matched experiment fantastically accurately. This process of removing the infinities was called renormalisation. Many famous physicists found it deeply unsatisfactory. They thought it might just be a symptom of a theory that could be improved.

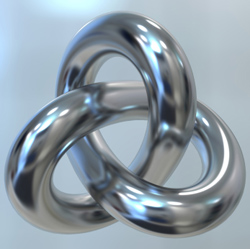

This is why string theory created great excitement in the 1980s and why it suddenly became investigated by a huge number of physicists. It was the first time that particle physicists found a finite theory, a theory which didn't have these infinities popping up. The way it did it was to replace the traditional notion that the most basic entities in the theory (for example photons or electrons) should be point-like objects that move through space and time and so trace out lines in spacetime. Instead, string theory considers the most basic entities to be lines, or little loops, which trace out tubes as they move. When you have two point-like particles moving through space and interacting, it's like two lines hitting one another and forming a sharp corner at the place where they meet. It's that sharp corner in the picture that's the source of the infinities in the description. But if you have two loops coming together, it's rather like two legs of a pair of trousers. Then two more loops move out from the interaction — that's like sewing another pair of trousers onto the first pair. What you get is a smooth transition. This was the reason why string theory was so appealing, it was the first finite theory of particle physics.

Cosmological infinities

Simulated view of a black hole. Image: Alain Riazuelo.

Another type of infinity arises in gravitation theory and cosmology. Einstein's theory of general relativity suggests that an expanding Universe (as we observe ours to be) started at a time in the finite past when its density was infinite — this is what we call the Big Bang. Einstein's theory also predicts that if you fell into a black hole, and there are many black holes in our Galaxy and nearby, you would encounter an infinite density at the centre. These infinities, if they do exist, would be actual infinities.

People's attitudes to these infinities differ. Cosmologists who come from particle physics and are interested in what string theory has to say about the beginning of the Universe would tend to the view that these infinities are not real, that they are just an artifact of the unfinished character of our theory. There are others, Roger Penrose is one for example, who think that that the initial infinity at the beginning of the Universe plays a very important role in the structure of physics. But even if these infinities are an artifact, the density still becomes stupefyingly high: 1096 times bigger than that of water. For all practical purposes that's so high that we need a description of the effects of quantum theory on the character of space, time and gravity to understand what goes on there.

Something very odd can happen if we assume that our Universe will eventually stop expanding and contract back to another infinity, a big crunch. That big crunch could be non-simultaneous because some parts of the Universe, where there are galaxies and so on, are denser than others. The places that are denser will run into their future infinities before the low-density regions. If we were in a bit of the Universe that had a greatly delayed future infinity, or even none at all, then we could look back and see the end of the Universe happening in other places — we would see something infinite. You might see evidence of space and time coming to an end elsewhere.

But it's hard to predict exactly what you will see if an actual infinity arises somewhere. The way our Universe is set up at the moment, there is a curious defense mechanism. A simple interpretation of things suggests that there is an infinite density occurring at the centre of every black hole, which is just like the infinity at the end of the Universe. But a black hole creates a horizon around this phenomenon: not even light can escape from its vicinity. So we are insulated, we cannot see what goes on at those places where the density looks as though it's going to be infinite. And neither can the infinity influence us. These horizons protect us from the consequences of places where the density might be infinite and they stop us seeing what goes on there, unless of course we are inside a black hole.

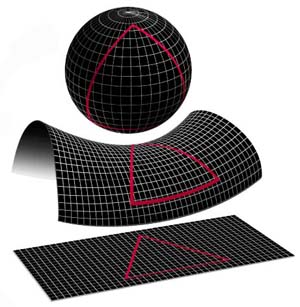

Another question is whether our Universe is spatially finite or infinite. I think we can never know. It could be finite but of a size that is arbitrarily large. But to many people the idea of a finite Universe immediately raises the question of what is beyond. There is no beyond — the Universe is everything there is. To understand this, let's think of two-dimensional universes because they are easier to envisage. If we pick up a sheet of A4 paper we see that it has an edge, so how could it be that a finite Universe doesn't have an edge? But the point is that the piece of paper is flat. If we think of a closed 2D surface that's curved, like the surface of a sphere, then the area of the sphere is finite: you only need a finite amount of paint to paint it. But if you walk around on it, unlike with the flat piece of paper, you never encounter an edge. So curved spaces can be finite but have no boundary or edge.

To understand an expanding two-dimensional Universe, let's first think of the infinite case in which the Universe looks the same on average wherever you go. Then wherever you stand and look around you, it looks as though the Universe is expanding away from you at the centre because every place is like the centre. For a finite spherical universe, imagine the sphere as the balloon with the galaxies marked on the surface. When you start to inflate it the galaxies start to recede from one another. Wherever you stand on the surface of the balloon you would see all those other galaxies expanding away from you as the rubber expands. The centre of the expansion is not on the surface, it is in another dimension, in this case the 3rd dimension. So our three-dimensional Universe, if it is finite and positively curved, behaves as though it's the three-dimensional surface of an imaginary four-dimensional ball.

The sphere has positive curvature, the saddle has negative curvature and the flat plane has zero curvature. The triangles are formed by drawing the shortest lines between pairs of points. Where the sum of the angles exceeds (is less than) 180 degrees the surface has positive (negative) curvature. When it equals 180 degrees the surface is flat, with zero curvature. Image courtesy NASA.

Einstein told us that the geometry of space is determined by the density of material in it. Rather like a rubber trampoline: if you put material on the trampoline it deforms the curvature. If there is a lot of material in the space, it causes a huge depression and the space closes up. So a high density Universe requires a spherical geometry and it will have a finite volume. But if you have relatively little material present to deform space, you get a negatively curved space, shaped like a saddle or a potato crisp. Such a negatively curved space can continue to be stretched and expand forever. A low density Universe, if it has a simple geometry, will have an infinite size and volume. But if it has a more exotic topology, like a torus, it could also have a finite volume. One of the mysteries about Einstein's equations is that they tell you how you can work out the geometry from the distribution of matter, but his equations have nothing to say about the topology of the Universe. Maybe a deeper theory of quantum gravity will have something to say about that.

About the author

John D. Barrow is Professor of Mathematical Sciences at the University of Cambridge, author of many popular science books and director of the Millennium Mathematics Project of which Plus is a part.

Barrow is the author of The infinite book: A short guide to the boundless, timeless and endless, which tells you lots more about infinity. His Book of universes is also relevant to the last part of this article about cosmology and string theory. See the links below for both books.

Comments

Anonymous

John, I have a question another possible 'reality' for infinities.

Why not count motion? Bear with me...

If we don't have infinities, then we don't have irrational numbers and Xeno's paradox keeps us from ever arriving at our destination.

I realize there are multiple ... lets say routes to dealing with the resolution to Xeno's paradox but in one sense why not say that its the irrational numbers that let us arrive at a destination? - whether that destination be arriving at 1 from 0 or arriving at the finish line of a race.

I say this because since there is an infinite number of rational numbers between any two rational numbers we could have the paradox play out anytime we want to 'jump' or move anywhere. we can't step from one rational to another because of the 'gap' in between them. But once we have irrationals there is a continuity to physical space that lets us 'move', or at least prove that we did. If we were simply drawing a line with a pencil on a paper we couldn't get from A to B with only the rationals, but once we have the irrationals we can draw the line continuously. ... ok, a bit weird maybe, but could you under any stretch of the imagination by this is a 'physical' thing? (I'm also implying that this sort of knowledge of rationals, irrationals, and infinities is what lets the infinite series converge and hence allows us to 'arrive' at a particular destination - or number)

thanks!

Anonymous

.... "there is an infinite number of (ir)rational numbers between any two rational numbers " ....

There is also an infinite number of rational numbers between any two irrational numbers

Anonymous

Close, but no cigar. It's true to say that there exist many irrational numbers which are seperated by an infinite number of rational numbers. But not that there are an infinite number of rational numbers between any two irrational numbers, since there are irrational number between which zero rational numbers exist, between which one exists, between which two exist, etc..

Anonymous

No. There actually are an infinite number of rationals and irrationals between any two rationals or irrationals.

You claimed that sometimes two irrationals have no rationals between them. That's clearly false. For example, if you picked these two irrationals:

3.26543215676542463668856435...

3.26597755365236434542245653...

Then you can find a rational between them like this. Just truncate the larger number after the first digit where it differs from the smaller number:

3.2659

That is guaranteed to be a rational that's between the two irrationals. If you prefer rationals written as fractions, then just write it over a power of ten:

32659

-------

10000

And that fraction is guaranteed to be between the two irrationals. So you can never have zero rationals between them.

In fact, by truncating later and later, you can generate an infinite number of rationals, all of which lie in between the two given irrationals. And clearly, the above procedure works, no matter which two irrationals you choose, as long as they're different and positive. And it works with slight modifications for negatives, too.

Anonymous

hmmm. I'm confused about this. but is there some differences between forever?

Anonymous

Therefore the amount of time between each point as well as the distance gets smaller. The amount of time is therefore finite, even if the amount of jumps are infinite.

Anonymous

Zeno's paradox is an interesting mathematical construct, but does it really exist in the real world? Do you really need infinity to describe motion? Only in an infinite universe. A finite universe doesn't require infinity to describe motion. Think of it like pixels in a video game. It doesn't make sense to say that there are an infinite amount of pixels between two pixels, because you know there are a finite amount of pixels on your screen (1920x1080 for example). But yet you see motion in your video game. Why? Motion is an illusion. There are only instantaneous state changes, that occur so rapidly and at such small scale our brains interpret them as the abstract concept of motion.

Our brains are also finite and therefore can only process a finite amount of information in a given period of time. However we want to draw conclusions and make predictions even though we only ever observe a tiny bit of the information thrown at us. We can use mathematics to make assumptions about the information we never directly observed. This proves helpful in most situations, but could also lead us to incorrect conclusions.

Could the real universe be the same way? There are a finite amount of atoms between two points on a sheet of paper.

Are there a finite amount of particles within an atom? An electron? A quark? No one can say for sure... yet.

I'm not a physicist, but it is interesting that the wiki page http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quark does not ever use the words infinity or infinite.

So is infinity a mathematical construct, or does it really exist?

Anonymous

I have wondered about this. I like your pixel analogy, I think I will use that when I try to describe this issue to people. One of the things that im curious about this is that, doesn't Zeno's paradox prove that we must live in a finite universe? I hope Im thinking of the right paradox here. Is this the one to do with finishing the race? and that in order to do so you must first cross the half way line, and then in order to do that you must cross the quarter-line. and keep asking this question ad infinitum.... If we do live in the pixel universe then interesting questions regarding neutonian motion crop up. Particularly his laws concerning the conservation of energy regarding momentum. In a pixel world (im using pixel here to denote 'the smallest possible unit of space') surely in order for objects to move at different speeds some will need to effectively 'stop' for a short period of time, and then after a certain really really small amount of time has passed, 'teleport' to the next pixel along? The start/stop nature of that means that neutonian momentum only holds true for macro-scale objects but not on a micro-scale (and we all know what schrodinger would have to say about that).

bearing all that in mind. Im curious what conclusions other people might draw.

any thoughts anyone?

Anonymous

Zeno's paradox says that motion is not possible, hence the paradox. It was solved by using infinite summations, i.e. integrals. However if space is not smooth, which an integral requires, but quantified then it is just an abstract mathematical model to the real problem. The math would then not correspond to reality. Reality would them be more like a video game in where particles vanish in one position and appear in another. The video game description is similar to the condensate describe in quantum field theory in where particles can vanish into the condensate or be extracted from the condensate and give the illusion of a particle moving through space.

Enai

But the video game analogy fails, because the real world is not made of pixels- it is continuous. That's the whole point of the dichotomy- for any given interval, you can always halve the interval. There is no atomic unit at which point further division is impossible (at least, conceptually impossible- certainly there are intervals that are not practically or physically divisible).

So, the dichotomy doesn't require the assumption that space is infinite (i.e. infinitely large), only that it is continuous and therefore infinitely divisible. And what, exactly, is paradoxical here depends on the construction of Zeno's argument- on the classic Aristotelian interpretation, we end up with an infinite number of sub-intervals, each taking some positive (non-zero) duration to traverse. If we have to do an infinite number of tasks, each with some non-zero duration, then it would take us an infinite duration- we would never arrive. Or so the argument goes. Obviously, contemporary maths to the rescue here. But one other construction of the paradox is to conclude that there is no FIRST interval, such that the traversal of which sees us begin our journey, and no LAST interval, the traversal of which sees us arrive at our destination. Though this is more of a counter-intuitive result rather than any contradiction, it can't be dealt with quite as easily as the traditional version of the paradox.

Patrick

You are just assuming the real world is continuous. There is absolutely no evidence for that. Current physics would have us believe that the Planck distance is the smallest unit of distance, i.e., our pixel. Is it? We don't know. But there is certainly no evidence that the universe is continuous.

Ron C

Infinity could be defined as something that resides outside of space and where time doesn't flow and never did. If space and time have a beginning then they could only come from something that doesn't have a beginning. The concept of beginning is tied to time, if time didn't exist, then whatever it came from, is infinity. The universe could be infinite but it isn't infinity. Infinity is everything that is.

It's difficult for us to understand because we are inside of the universe. Our thoughts are limited by space and time, we can't think outside of them because we can't imagine any existence outside of them. For us, nothing can exist outside of space and time. Yet, if we see that time had a start, something before it must not have had one. The same goes for space, if it had a start then it must have been that it didn't exist before, this is hard to express: there must be a place where space and time do not exist at all, a place that isn't a place where time doesn't flow?

Some fields of science advance the universe came from infinite potential or possibilities. They seem to support the concept of infinity.

Let's say that one possibility (the one we exist in for example) out of all the infinite possibilities is taken out to put the universe into it. It could be expressed very simply:

∞ - 1

Since even though something was taken out of it, infinity itself didn't change. So it's logical to say:

∞ - 1 = ∞

Where does the 1 exist? Now we can see that whatever was taken out of infinity is still part of it. The 1 that was taken out can only exist inside of infinity.

Physics looks at this from the inside out, inside the 1 looking out at infinity. Maybe that's why infinities come up everywhere and no one can figure out the mass of the universe. These infinities may not be flaws or errors, they could be that infinity is showing through there, only we don't account for it because we are looking from the inside.

The paradox is how could the universe not dissolve back into infinity. Since it is part of infinity there is no particular identification for that specific potential

Imagine the universe is a drop of water in the ocean. It has its own identity, well, because it exists and there is something in it that notices the existence. How is it possible for it to maintain it's identity or existence inside the ocean? it automatically mixes with the water and all trace of the individual drop is gone forever. In this scenario, the universe exists inside infinity. You could argue the degree of existence it has. One way it could exist without disappearing in infinity is if it's shielded from 'realizing' it is inside and part of it.

Another example with water, if you want to make a hole in it, you have to keep it spinning. As soon as you stop the hole is gone. Maybe infinity has the same kind of property, the universe has to keep spinning so its own space would continue to exist inside of infinity. Maybe, the reason we can't put our finger on the mass of the universe or explain why so many infinities are showing up all the time is because the universe has a finite mass that is growing inside of infinity.

Here is a link to an essay I wrote about the same. It may have some additional info for those interested.

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1GzFPlU9So5o7MOyiDCOhyjp9KHL7oBKxBnz…

Anonymous

Zenos paradox is nothing but semantics.

If I have 1 slice of pizza..you look and see 1. 1 is actual. If I have 2--you see 2. They are actually 2.

If I then show you a pie with 2 slices missing and you look at the whole of all--you could say the 2 whole pieces of pizza are 2 tenths of the pie--but that is only in RELATION TO THE PIE. A FRACTION IS NOTHING BY ITSELF. 2 is not 2 because its one more than 1. Its 2 in reality. It doesn't have to stand in relation to ANYTHING to be 2.

Its 2 on paper and in reality. The fraction is NOTHING in reality. I cant chop up my slice and claim that slice was infinite. It was just 1. If it was infinite the entire world could eat from it and be FULL FOREVER.

So what we have here is human being playing games with paper and denying reality. There are no infinities. There is infinite stupidity as Einstein said. This is bias overruling logic to justify an end. Every example used fails and anyone trained in logic sees that in all of 3 seconds.

Q

The principle describes an infinite number of infinitesimals (or an infinite series tending to an infinitesimal for Xeno's paradox), not whole numbers. It is because of this that infinites can produce finite values.

Anonymous

Divide your pie by three exactly accurately please. You can not. You will need an infinite amount of time and accuracy to perform this task.

Anonymous

I am surprised you didn't mention continuous, uncountable infinity vs. infinite arrays/lists.

For example, temperature, while we know that due to quantum mechanics, it is in fact digital, Aristotle would probably have thought that it was analog, smooth.

These are measured as real numbers.

You can count to 10, 57, or 4.

You can even count to -9, 0, etc, by counting like this:

0,1,-1,2,-2,3,-3...

You can even count to -562/197 if you are clever.

1/1, -1/1, 1/2, -1/2 2/1, -2/1, 3/1, -3/1, 2/2, -2/2, 1/3, -1/3. This will eventually reach -562/197. It will be the 315676th item in the list.

But, try and count the irrational or real numbers.

some hypothetical way of counting:

a.bcde...

f.ghij

k.lmno

p.qrst

u.vwxy

but.... I can think of a number that isn't on that list, it has the first digit of the first number, plus 1, as its first digit, second of second, +1, as its second, etc. Basically, I can do this no matter what crazy scheme you count with.

I guess +1 means +1 mod 10 in this case, since we don't want a 10 as a digit.

Anonymous

Thank you, thank you, thank you . . . (ad infinitum), Anonymous, for some common sense rather than the abundant sophistry thrown out about infinity. I do not exclude Cantor!!! There are no infinities larger than any other, because no matter what 'sophist...icated' and clever scheme you may contrive to create the illusion of differing orders of magnitude, the fact remains that infinity, by the very nature of the concept, is NOT A NUMBER and an infinity of anything is not (by definition) an amount, and is NOT A MAGNITUDE. Comparisons and distinctions of quantity or magnitudes cannot be made of 'things' (concepts or otherwise) that are NOT quantities or magnitudes! Every type of 'infinity', by definition, goes on forever, it never concludes. Demonstrating that a counting system can be set up for some and not for others says nothing about the magnitude, or relative magnitude of either. Each goes on forever regardless of whether we can conceive one-for-one relationships between or among them.

Anonymous

.... If it *acts* like a number........?

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hyperreal_number

Anonymous (the same one)

So how does it "act like a number"?

Additional comment: I don't care what kind of infinity or infinite set you may define, I can count them one-for-one as you produce another number from it. Forever. So what's so deep about showing gaps in any proposed ordered counting system? None. Infinity is not a number. Any infinity can be counted by the natural numbers forever. It's smoke and mirrors to say any infinite set is larger than another (assuming, without accepting, that the term 'infinite set' actually has any meaning. Can a "set" be an unbounded amount? Possibly only in fantasy, which is what most discussion of infinities amounts to.

Angel

"Infinite set" actually has a formal definition and such sets do exist. The set of all the natural numbers exists, and therefore, the size of the set also exists. That size happens to be a non-finite number called Aleph-Null. Your argument is wrong. And it does behave like a number because you can do basic arithmetic with it.

Matt

"There are no infinities larger than any other"

This is a problem with our finite way of thinking. The truth is that while correct, there are infinities which "subsume" other infinities, creating what we might call a hierarchy, but it is a different kind of hierarchy than we are accustomed to. It is a hierarchy not based on quantity, but based on quality. The quality of one infinity vs the other is based on an infinite containing the qualities of another infinity or not, because the total "amount" is necessarily equally infinite, but of different quality.

Anonymous

In regards to time, surely 'infinity' is practically impossible. Since the concept of something neverending means that the number is always unattainable. It continues, infinitely, throughout time, but never can it BE infinite.

At no point in time is something ever 'of infinite value'. But presently, it continues. And it continues. And it continues, always.

Therefore, the only possible infinity able to be 'of infinite value' is one that exists outside time?

Bernard Rooney

Well said

Anonymous

Infinity is the NON-EXISTENCE of a limit. If a NON-EXISTENCE existed, it would not be a NON-EXISTENCE.

Anonymous

I can fully agree with the view that infinity is essentially the lack of boundary. However, the conclusion drawn from this in the previous post is nothing but a pseudo-philosophical game of words. Here is an even worse example: "existence is the non-existence of non-existence". You get nowhere with this.

If one looks carefully at the mathematical practice of set theory, it may be noticed that the members of a sets are rarely "being collected"; only very small finite sets arise like this. Instead, one considers a defining property of the elements to be collected. When presented a potential element, one can (in principle) decide whether it satisfies the property or not. In programming, this is called "lazy construction". As all mathematical thinking is evidently finite, one will never face "actual infinity", but just finite formulations of properties.

In regard of Cantor's result, there are more subsets of the natural numbers than one can formulate properties. So there must be subsets without a defining property. Not surprisingly, little can be said about them (except that they must be infinite). They are like most of the transcendental numbers: vague generic objects filling the container. It should not be surprising that hard questions may arise with such objects, like the existence of sets with cardinalities in between countable and continuum.

Anonymous

Infinity is no more a set than 'nothing'. A set is defined. Nothing and infinity are not. Describe for me something that neither has nor lacks quality, quantity or location. Like infinity, nothing is the absence of a set.

Angel

That is not true. Nothingness is a set, called the empty set.

Matt

"existence is the non-existence of non-existence . You get nowhere with this."

Actually you get everywhere with this (pun intended). But joking aside its factually true. The reason is that we have come to understand that "nothing" does not actually exist. There is always a non-zero state of energy due to quantum effects of sub Planck length quantum phenomena. Therefor we can conclude that existence is indeed the non-existence of non-existence because non-existence does not exists. A perfect vacuum devoid of any and all energy is impossible. Interestingly, in order to describe the phenomena that arises out of this "quantum foam", ie virtual particle pair collisions and interactions, we use Feynman diagrams which take the average of ALL INFINITELY POSSIBLE interactions. Some say this is a trick of mathematical representation that incorrectly approximates real world phenomena, but it has never been disproven that Feynman diagrams do not actually describe the average of the summed total of infinite probabilities.

Anonymous

if we follow your way of argument we can argue that: darkness is non-existence of light. if a non-existence existed, it would be a non-existence. but we know that shadow exist.

we can make many arguments by this form. but this kind is just a fallacy.

Hadi

Anonymous

No. The fallacy is yours, not of the poster you're responding to. "Shadow" is just a name we made up to describe the non-existence of light. Naming it does not make it 'something' - it is only a name which refers to the absence of something.

Something that is, by its very definition, a non-existence, cannot 'exist' in any physical or logical sense.

Anonymous

No, actually, shadow is the wrong term. The correct word is darkness. Darkness is non-existence of light. If non-existence existed, it wouldn't be a non-existence. but we know that darkness exist.

"Infinity is the NON-EXISTENCE of a limit. If a NON-EXISTENCE existed, it would not be a NON-EXISTENCE."

Who says non-existence if it exists, doesn't remain a non-existence. Non-existence of black spots exists in a completely white paper.

Non-existence of protons exists in electrons. Non-existence and existence aren't two opposite QUANTITIES which can be cancelled if they appear together. They are just concepts. Just substitute exist with a different verb, e.g. occur, in your sentence and your problem would be resolved.

Anonymous

Hi,

There is a new common sense approach to infinity called 'Extreme Finitism' (see http://www.extremefinitism.com/).

The website has some interesting articles including an INVESTIGATION OF INFINITY IN MATHEMATICS (see http://www.extremefinitism.com/background/).

One article has the definitive answer to the question 'does infinity exist?' (see http://www.extremefinitism.com/blog/does-infinity-exist-the-definitive-…).

This website takes a common sense approach, and so people who like the weird things made possible by a belief in infinity will be sorely disappointed.

Enjoy.

Anonymous

Infinity isn't something we can hope to understand yet. How can you add one to a number and it be the same? It follows none of the rules of normal numbers. If you add up all the integers and fractions before it you will get 0. (1-1) + (2-2) = 0.

We can't solve the problem of infinity because it CAN'T exist. There is ALWAYS a limiting factor to everything. Amount of space, amount of paper, amount of particles in the universe! If there is always a limiting factor, then nothing can be endless. So infinity is a game, not a possibility.

hsaudio

Unfortunately, humanity (humans) will never know, or be able to fully understand infinity, or if it exists. Hypothetically, if you were able to prove that infinity does exist, then would that not make you God? I am not a religious person, but the answer to infinity lies with our creator.

Anonymous

My understanding is that the universe is always expanding and is therefore Infinite. But if we had the tools and we could break the speed of light could we measure the different stages of infinity? The explanation that the universe started with a big bang then expanded and suddenly expanded by infinity does not make too much sense to me. We are able to measure a less than 1 millisecond after the big bang. That is still something and a number that we can measure from the stages to infinity isn't it? An example would be that we could measure how "big/long" "the end" of the expanding universe was 4 billion years B.C.

Please give me an explanation as to why my "theory" is stupid/asinine seeing as i am not a scientist nor a well educated Pearson.

Thank you.

- Idiot from Norway. age 20.

Anonymous

I feel as this article is trying to discredit some of the great theologians such as Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz who attempted to use reason to prove the need for a being to begin the universe(an unseasoned reasoner). Let me explain why these philosophers are right about the non-existence of infinities. The most basic of these arguments was made by the Christian philosophers and perfected by Muslim philosophers and was called the Kalam argument. It attempts to prove that the universe had a beginning and is not infinite. So, first, what is an infinity? An infinity is a limitless quantity, in other words, an infinity, by definition, cannot be quantified. The kalam argument looks at two types of infinities: potential and actual. A potential infinity is like a stop watch, if you hit start it could, potentially, continue adding numbers onto each other for a limitless amount of time. but as soon as you hit stop the number that the watch has counted to becomes quantifiable and no longer an infinity. The other type of infinity, an actual infinity, is an unquantifiable amount of something, something that cannot be calculated because it goes on and on forever. The argument then proves that time had to have a beginning and is not infinite. the best way to do this is to observe that there is a "now". If now exists time cannot be infinite. Ok, picture "now" as a destination on a set of train tracks. now picture time as the train tracks that are infinitely long. How far would you have to travel to reach your destination? if you fell into a bottomless pit, how far would you have to jump to get out of the pit? what would you jump off of? There is no point of reference in an infinity because it is unquantifiable. Ok, so time isn't infinite, so what? The impact of this is that there had to be a point when NOTHING existed. So then why does the universe exist, did it one day in its nonexistence decide to pop into existence. This is impossible because A) the universe is not personal and cannot decide B) something that does not exist cannot reason itself into existence. This brings us to the conclusion that there is something that is immaterial, personal, self existent, "outside" of time, and logically necessary that started the universe.

Anonymous

You do realise that you're wrong on several accounts and that Kalam argument doesn't work, right?

I will criticise a couple of points briefly. Firstly, if time of universe's existence is finite ('time' is not a proper word here, which you seem to have ignored) then there's no reason that there has to be a point that nothing existed. Secondly, I can also say that that something "immaterial, personal, self existent*, 'outside' of time*, and logically necessary" (* whatever that means) couldn't in its timeline exist without a cause, as, because its time also cannot be infinite, it couldn't "reason itself into existence", and there is something else that is "immaterial*, personal, self existent, "outside" of "outside" of time, and logically necessary". Also, requiring that "logically necessary" thing to "exist 'outside' of time", be "immaterial", "personal", "self existent" because "universe can't decide to reason itself into existence" is jumping to conclusions.

Also, are computers "personal" (as in, what you mean by the word "personal")? Because they somehow can vary their output depending on the input.

Also, the Kalam argument is irrelevant to the topic.

Anonymous

Firstly, the Kalam cosmological argument doesn't state that there must be a point at which nothing existed, it simply states that there was a time before which there was no time (or space, or matter, or anything else actually.) And this is supported by the majority of astrophysicists and other scientists. Secondly, the idea of a timeless, spaceless, immaterial, incredibly powerful Being who has aseity does not jump to any conclusions. It can be deduced from the properties that must be assigned to whatever caused the universe, whether that was God or not. The only alternative to that would be that an abstract object caused the universe to exist, but that simply makes no sense because abstract objects simply have no causal properties.

bruce

The one thing that no proponent of the KCA has ever provided is the cause of the first event. Now you might reply - this was the First Causer (aka the Personal Creator or whatever name you want to use). But this refers to the causer not the cause. So you need to identify what the First Causer did first. The problem that you face is that the First Causer exists unchanging. And to do something requires change. But this is impossible for something that is unchanging. But then you can re-define some words to provide a way out of this, just as other proponents have done...

Anonymous

Infinity is the non-existence of a limit. If a non-existence existed, it wouldn't be a non-existence.

Anonymous

The nonexistence of a limit could also just mean that space,time, light, and matter are constantly being created everywhere not that nothing exists but if you want to get philosophical with it go ahead. Nothing is still a thing.

Anonymous

The article states that infinities in Quantum Electrodynamics is viewed as renormalization problems. However, it is my understanding of Quantum Field Theory (QFT) that infinities are not just a matter of a renormalization problem but a necessary property of the condensate - otherwise the theory would not work at all.

So if my understanding of QFT is correct, what does that leave us at?

Anonymous

Thank you for this page.

I am sick of hearing about how there are an infinite number of worlds so there is one just like this one....

Infinity is an old human concept, usefully employed in mathematics as 'shorthand' for very huge. But it isn't a 'thing' - it can never 'be' (because you never get there).

If the mass at the centre of a Black Hole was infinite why don't they just swallow up the whole universe like a huge reverse-big-bang vacuum cleaner, why have a horizon at all if you're 'infinite'?

The nonsense theories appear to be due to the paradoxes caused by trying to take this 'concept' literally.

Anonymous

(and this all is based on an if)

If we could live an infinite amount of years, yes we could discover an infinite amount of planets. but physical limitations disable us from ever reaching infinity, such as our universe ending, our solar system ending, our world ending, us physically dying. all which work. but what is to say the dwarf planet pluto, is non-existent...i mean, no body has ever physically set foot on pluto, but to say it is not real is stupid...obviously pluto is real...that being said, just because infinity has not been reached that does not prove it isnt there...obviously infinity is a term to represent all possible numbers, but physical limitations stop us from doing mental realities

Bert

An infinity of pulsing big bangs, we're here. Only one place, here. Now, how can WE fix things?

Q

What interests me most about the possible existence of physical infinites is their ability to predict an infinite number of universes (under the multiverse theory)

If space is indeed continuous, there could be infinite possible positions in which something could be (in exactly the same way as there are infinite numbers between 0 and 1) and for a probabilistic event, such as the position of a quantum particle, an infinite number of universes would be required (again, assuming its truth) to describe the position in spacetime of that particle alone.

Sukumar Roy

In order to answer the question, Prof. Barrow starts with Aristotle's philosophical interpretation of the concept of "infinity" - thereby implying that he was the first.

However, and according to Wikipedia, though Aristotle came up with the philosophical basis in 350 BC, "The Jain mathematical text Surya Prajnapti (c. 4th–3rd century BCE) classifies all numbers into three sets", of which "infinity" was one.

Like most other things in history, the philosophical basis of a concept came first and those that were proven scientifically got accepted later. Seemingly, "infinity" is such a concept.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Infinity

Most children growing up in India are introduced to the Sanskrit word "Ananta" which PRECISELY means "infinity".

If the "mathematical basis" came in c. 4th–3rd century BCE, chances are that the "philosophical" basis of "infinity" - "Ananta" - must have come even earlier!!

Perhaps Prof Barrow should remove his colored Euro-centric glasses and address the philosophical basis of "infinity" more accurately and thereby more profoundly!!

Matt

"The places that are denser will run into their future infinities before the low-density regions."

Could you expand on this further? I'm interested in understanding why this is the case. Thanks